Navigating the socioeconomic perils of Covid-19 in Bangladesh

Despite the depressing state of major indicators such as negative export-import growth; large revenue deficit; falling private sector investment; rising non-performing loans recorded in the last quarter of 2019, as well as the impending fear of a global economic recession, the government of Bangladesh has been optimistic that the depressing trend of these indicators could be reversed and instead lead to another great year—with respect to growth and poverty reduction. But this optimism has now been seriously dented with the severe onslaught of Covid-19. It has virtually stalled all economic activities all over the world.

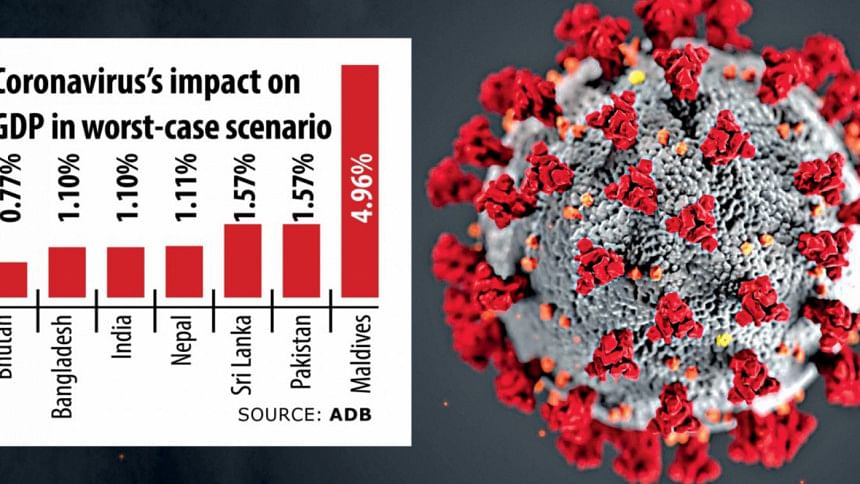

Many countries and multilateral agencies have now started to count the economic and social costs of Covid-19. The preliminary estimates emerging from a few sources are frightening. JP Morgan has slashed its USA GDP forecast for the next quarter (i.e. second quarter) by 25 percent and projected an imminent recession, despite "Herculean" stimulus measures equivalent to USD two trillion from the US government. The title of the OECD Interim Economic Assessment, published on March 2, 2020, was "Coronavirus: The world economy at risk". Similarly, Modi's government cut India's economic growth forecast from 5.3 percent to 2.5 percent for 2020. Similar dire projections have emerged from other reports and briefs.

The Bangladesh economy will not be spared. The impacts of Covid-19 on economic growth, job losses and upsurge in poverty are expected to be large. The projected GDP growth of 8.2 percent for 2020 may decline by 2 to 3 percent—that is, economic growth may settle somewhere between 5 to 6 percent. Robust economic growth during the last decade helped Bangladesh to win her fight against poverty—mainly through employment generation channels. According to current projections (before Covid-19), the poverty rate will still be 20 percent in 2020, with almost 32 million living in poverty. Poverty measurement use a poverty line (PL) threshold to identify poor persons. If per capita income is lower than the PL by even one Taka, he or she is considered as poor. Like many other countries, Bangladesh adopts a low PL in monetary value compared to international poverty lines, such as USD 3.2 for lower middle-income countries and USD 5.5 for upper middle-income countries—suggesting that large numbers of the population are vulnerable even if they are not counted as poor. A reduction in economic growth, along with a rise in joblessness, will inevitably lead to a sharp increase in the poverty rate and push more people into poverty. The number of vulnerable persons who will need assistance may rise exponentially in 2020, although perhaps for a temporary period, especially since vulnerable groups in Bangladesh lack the savings and resources required to fend off the impacts of Covid-19.

Like many other countries, the Bangladesh government has also proposed a series of measures and stimuli to buttress the consequences of the pandemic. These are welcome initiatives. Support is also being provided by the private sector, NGOs and other development partners. Addressing the health risks and the social and economic perils faced by vulnerable populations should be the main focus of the government stimulus measures. The size of the stimulus may need to be around 4 to 5 percent of GDP. Bangladesh will also announce its budget for the next fiscal year (FY2020-21) in June 2020—amid the Covid-19 pandemic. The budget should reorient its focus and channel resources from traditional sectors such as energy and physical infrastructure to social protection, poverty alleviating programmes, health insurance and universal health programmes, as well as programmes for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The government could increase current social protection allocation of 2.2 percent of GDP to about 5 percent of GDP during this crisis period. Employment generation and poverty alleviation programmes should also attract higher allocations of the budget. The health sector budget should be permanently increased to 3 percent of GDP from the current allocation of less than 1 percent of GDP. Along with fiscal measure (tax and subsidy) and utility measures (lower rates and deferred payments), Bangladesh Bank may create special funds to support SMEs to overcome the Covid-19 economic crisis.

A major plus point in the case of Bangladesh is that fiscal and monetary instruments are already in operation (even though they are not highly efficient), through which these stimuli can be implemented. Operations of digital finance service providers such bKash, Rocket and Nagad will be the key conduits for fast and efficient low-cost fund transfers that avoid human contact. Another advantage in Bangladesh is the presence of effective clusters of Civil society organisations and NGOs. They, along with the government, can play an important role in beneficiary identification, delivering resources to poor and vulnerable populations, and monitoring the stimulus implementation. Effective and timely disbursement of funds are imperative to tackle the economic and social perils of Covid-19.

Value for money of public funds is generally low in Bangladesh, epitomised by cost overrun and delay in implementation. This is the time to break this trend and have high value for money from the proposed stimulus and the measures to be proposed in the next budget. The following steps may help improve this situation—coordinated planning to pull together all resources (public, private, NGO and development partners) for maximising prioritisation and allocation; creation of a dedicated cell within the Planning Commission for Covid-19 related projects with an aim to approve projects within ten days for the speedy delivery of cash, goods and services; and extension of support from Bangladesh Bank for the quick approval of loans for SMEs and for the effective and timely disbursement of funds.

Bangladesh is well known for its resilience, and we have many times in the past, surpassed expectations and overcome all obstacles in the end. Following on those, it is presumed that Bangladesh will eventually emerge as a stronger nation after weathering the perils of Covid-19.

Bazlul H Khondker, PhD is a Professor in Economics at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments