Nationalising educational institutions: Opportunity or threat?

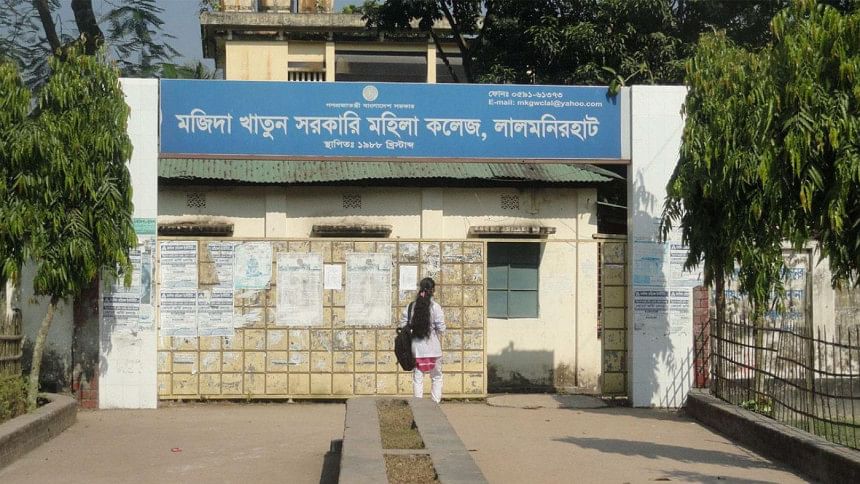

Since indepen-dence, a unique policy initiative in Bangladesh has been to nationalise non-government schools or colleges or madrasas. Another unique initiative has been bringing teachers serving in non-government educational institutions under the national payroll, otherwise known as the Monthly Payment Order (MPO). Of late, the current government has nationalised at least 271 non-government colleges and set aside Tk 15,000 crore in its national budget to meet expenditures required to enlist thousands of teachers serving in non-government schools/colleges/madrasas. However, does it create opportunities or threats for the students who enroll in these institutions?

General wisdom says, three types of resources are required to run an educational institution: (i) funds (ii) academic faculty and (iii) facilities. The need for an uninterrupted supply of resources occupies the centre-stage of any discussion about the education system in Bangladesh. It is assumed that non-government educational institutions are embroiled in financial crises that hamper the mission and vision of an institution. In order to create opportunities for students, nationalisation is considered a must to ensure an uninterrupted supply of resources. But besides the opportunities that are created by the nationalisation of non-government institutions, some challenges are also created, including lack of a sustainable supply of academics, lack of faculty accountability and absence of social responsibility among the local communities. In some instances, the challenges outweigh the opportunities.

I have collected quantitative data from 50 government colleges and 27 private colleges located in different parts of the country as part of my official responsibility in my current position. After analysing the data, it was found that on average the per-student expenditure in a government college and a private one (enlisted for MPO) is Tk 18,441 and Tk 37,766 respectively. That is, for a student, a private college invests twice as much as a government college. This finding is revealing: it indicates that the financial capacity of private colleges is relatively more than that of government colleges.

After nationalisation of the institutions, the ownership of assets is shifted to the government and, as a result, the authorities lose control over resource management which includes not only fund collection and disbursement but also teacher deployment, posting and transfer. A government institution runs as if it is a government office, having no authority over resource management. As there is a legal bar in place when it comes to receiving donations or contributions from sources other than the government, a government institution fails to diversify its sources resulting in inadequate financial resources in the nationalised institutions in the long run.

Another finding that has emerged from the analysis of the data is the high student-to-teacher ratio in government colleges. It was found that in a government college, the student-to-teacher ratio is 90:1 whereas in a private college, it's 43:1. That means, compared to non-government colleges, there are more students for every teacher in government colleges. Theoretically, a small student-to-teacher ratio is crucial for quality education. So non-government colleges are clearly in a more advantageous position. The root cause of this problem is lack of authority of a government institution over teaching staff management. By contrast, a private institution can exercise its authority over hiring and firing teaching and non-teaching staff upon approval of its local governing body.

Due to nationalisation of institutions, private colleges lose control over staff management too. For instance, when a non-government college located in a remote area is nationalised, the faculty and non-faculty members of the newly nationalised college become accountable to the central government rather than the local governing body or local community. In such a situation, some teachers resort to lobbying to be shifted to a district-level college—leaving the remote area where colleges already suffer from teacher shortage.

Another challenge is the lack of accountability amongst teachers. With the nationalisation of a private institution, the authorities lose control over its own teaching and non-teaching staff to a significant extent. Authority is concentrated in the centre, i.e. either the ministry or its agency. In the majority of cases, the local authorities of a government institution cannot hold a teacher responsible if he or she fails to fulfil his or her duty or responsibility. If a teacher has good political connections, holding him or her accountable becomes very challenging. In government colleges, there are instances where teachers take classes occasionally instead of regularly.

By contrast, the authorities of a private college can hold teachers responsible for their failure to perform their duties. A private educational institution can do so because the institution can hire and fire its teachers given its legal framework whereas a government institution cannot do so that easily.

So, the challenges associated with the nationalisation of non-government educational institutions are many, including inadequate supply of resources. Despite these facts, nationalisation of non-government educational institutions has been a popular political agenda of all governments in Bangladesh because of the strong link between education policy and political manoeuvring. However, perhaps it is time for policymakers to rethink this approach and consider some alternatives to mitigate these challenges so that the country can achieve its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) related to education by 2030.

Shamsul Arifeen Khan Mamun, PhD, works as a National Strategic Plan Specialist for the College Education Development Project (CEDP) being funded by the World Bank. He can be reached at [email protected] or [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments