Why are children walking away from government schools?

Most of South Asia (with the exception of Bhutan, Maldives and Sri Lanka) is not on track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal education target of equitable, inclusive, quality primary and secondary education for all children by 2030. The distressing prognosis was shared in the Asia-Pacific Meeting in Bangkok on Education Goal 2030 (APMED-2030) with government and civil society representatives, hosted by UNESCO and UNICEF, between October 1-4. A major reason for this situation, particularly in South Asia, APMED participants agreed, is the poor quality of public schools from which desperate parents are walking away and turning to private providers.

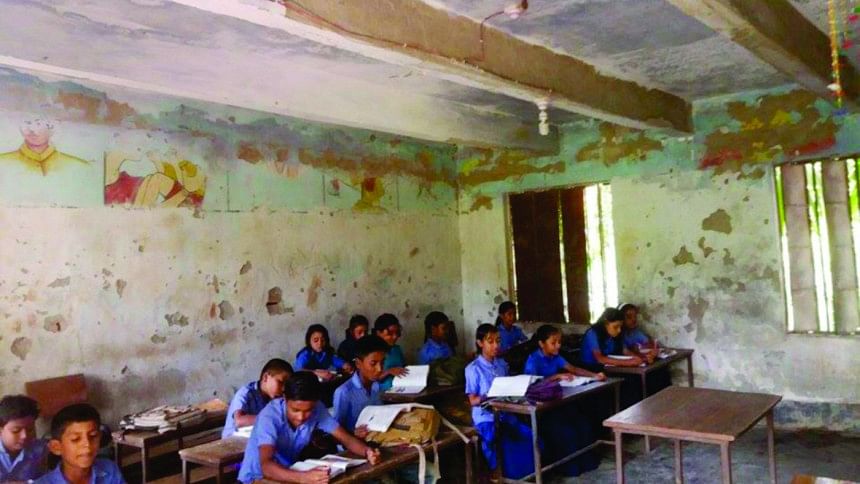

In Bangladeshi government primary schools, one teacher running two or three classes simultaneously (due to teacher absence), teachers not showing up in class on time, little accountability of school for non-performance, and unattractive and even unsafe school facilities, are regrettably not uncommon, especially in some 25,000 "newly nationalised government schools".

The non-government schools' share of primary school students has been rising rapidly since the beginning of this century. In the last 13 years, enrolment in established government schools has increased by eight percent, whereas the private kindergarten enrolment has soared by a thousand percent. The flight from government schools, which actually began in the 1990s, shows parental frustration with low quality government schools. Typically, families opting for the "low-fee" and not so low-fee private schools (known as kindergartens) are not the poorest. They have some discretionary income and place a high value on their children's education. The majority, however, is middle and lower middle-income families making great sacrifices for their children's education, finding no other option.

Non-government schools are diverse. They range from profit-making high-fee elite schools (mostly English-medium), to low-fee schools charging whatever the market bears. They also include NGO-managed schools (such as BRAC schools) which may charge a low fee when donor support is absent and faith-based schools (such as madrasas).

The problem of low-quality government schools obviously cannot be resolved by the expansion of non-government schools. By definition, these are not free, and not equitable or inclusive, especially the ones run commercially to make profit. Unfortunately, the government schools, despite policies to the contrary, are also not free, equitable and inclusive. There are various hidden fees in the form of charges for examinations, sports day, special events, and extra school-organised tutoring to prepare for the all-important end-of-class-five public examination. The highest cost for parents is the one for private tutors for their children which have become virtually mandatory even in primary school, because of poor instruction in the class and the need to do well in the class five public examination.

The situation at the secondary level is even more desperate in many ways than in primary schools. We have a hybrid system at this level with most of about 30,000 institutions (including Alia madrasas) being given a government subsidy for teachers' salaries (through what is known as the "Monthly Pay Order"). The schools are managed by local managing committees under regulations set by three main government agencies—the Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education, the Secondary Education Boards, and the National Curriculum and Textbook Board.

The problems that plague secondary education are many; at least three stand out. First, the three government agencies with responsibility for regulating and maintaining standards do not have enough capacity to do their job properly, and the three do not work with a coordinated approach for this purpose. There could be, for example, a team of qualified inspectors to supervise and support quality standards set by the three agencies. Secondly, the government salary subsidy is not sufficient to attract and retain capable teachers, and school managing committees are usually not able to mobilise sufficient extra resources (from student fees and other sources) for maintaining quality. Thirdly, the managing committees often, in a political culture of cronyism, do not represent true interests of parents and students. A fourth factor that should be mentioned is the widespread impunity and tolerance for corruption, inefficiency and mismanagement in the public sector as a whole.

The for-profit private schools are also growing at the secondary level. So far it has been around a hundred English medium high-fee proprietary institutions, which are accessible only to the elite. However, the quality deficits of the mainstream secondary schools are encouraging lower income parents to search for private alternatives. The kindergartens, which served the primary level students, have found a new market for extending their services to the secondary level.

A motley alignment of forces comprising private corporations, international financial institutions, bilateral aid agencies adhering to the political line of market as the ultimate solution, and proponents of the neoliberal market economy sense the opportunities for an education market worth billions of dollars. They are in effect spearheading a strong pushback against the idea of free, equitable, inclusive quality education ensured by the state based on the principle of right to education.

On the sideline of the APMED conference, the Asia and South Pacific Association for Basic and Adult Education (ASPBAE) held a workshop on what is called the Abidjan Principles. A group of 55 international human rights scholars, academics and activists, after three years of consultation and research, have adopted in February this year the "Guiding principles on the human rights obligations of states to provide public education and regulate private involvement in education." The principles are drawn from international treaties, conventions and agreements to which most nations have acceded as well as national constitutions and legislations.

There are 10 overarching principles, which are elaborated into 97 articles that would guide actions in respect of policy, strategy, programmes, regulating standards, assessing and modifying laws, provisions for resources and advocacy. These principles do not propose banishing private education, but assert the state's obligation to regulate education services, public and private, to serve the public good objectives of education and help fulfil the right to education.

The Abidjan Principles have been formulated in the context of growing threats to realising the right to education and achieving the SDG agenda. It is incumbent upon all concerned about right to education to examine, disseminate and act upon the implications of the Abidjan Principles.

So long as governing elites fail to commit themselves to major reform to improve government school quality, private schools will remain in demand and will be seen to be making a contribution by offering alternatives, even when they are not equitable, inclusive or of quality.

Dr Manzoor Ahmed is Professor Emeritus at Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments