Abul Hashim and Revisiting the United Bengal Plan (1946-47)

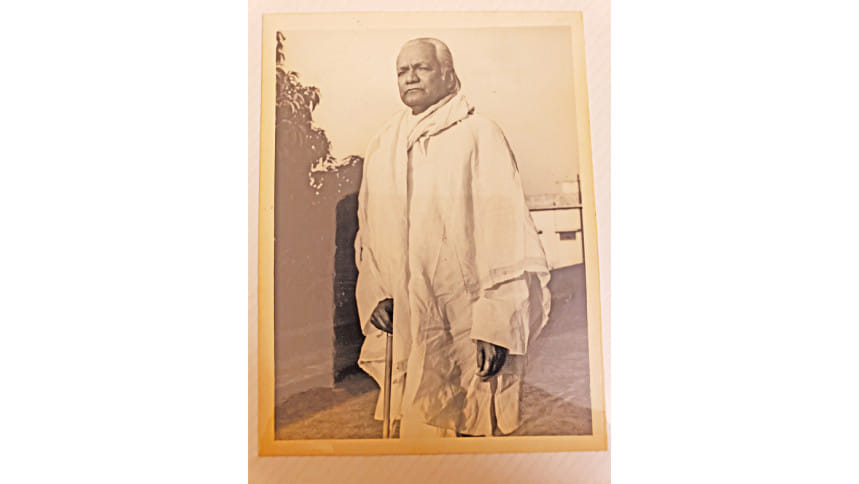

Fifty years ago, in October 1974, Abul Hashim, a prominent political leader of the then dissolved Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BPML) breathed his last in Bangladesh, leaving behind an important political legacy now long forgotten. Hashim had been an active member of the BPML and even served as its general secretary in the 1940s, important years leading up to the partition of British India. Buried deep under the enormous amount of historical literature, narratives and counter-narratives that deal with the Bengal province of that period, Hashim is often reduced to a footnote for his important contribution towards the United Bengal Plan of 1947.

The plan had been a last plea to the British government by the Bengal Congress and the BPML to keep Bengal united under all costs. It further demanded independence of this united Bengal and the establishment of a new Bengali nation-state with its eastern and western parts kept intact. A closer examination of this plan and Hashim's writings on issues related to nation-state, religion and modernity reveal a much deeper and profound understanding of his vision on the becoming of a nation that truly deserves a proper place in the existing academic discourse on nation-theory.

The general way to understand the construction of modern nation-states is typical through either of two frameworks or categories. First where nations and national sentiment sometimes is built around affective notions of solidarity, religion, and a sense of shared past, values, territory and practices. The second is the formation of nations built on instituting laws which are universal and secular. Throughout history, we have had nations which have been either ethnic or civic or more rarely a combination of the two. It is generally taken for granted that a nation can only be ethnic or civic and not be both together where ethnic identities and civic universalism are co-constituted.

In some sense Hashim's United Bengal plan was the political iteration of his deep philosophical understanding of what a nation truly ought to be. For Abul Hashim any new formulation of how a nation ought to take into consideration a new kind of public/political morality will have to seek to overcome narrow ethnic-religious prejudices and the myriad of problems associated with a society divided by both social and class inequalities.

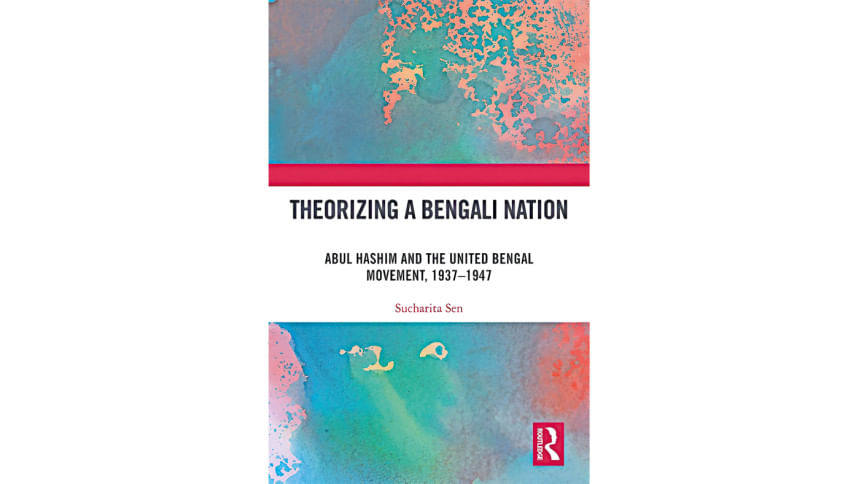

It is within this dual framework that my new book 'Theorizing a Bengali Nation: Abul Hashim and the United Bengal Movement 1937-1947' places Hashim's political contributions and philosophical iterations on what is a nation where I argue, he offers a third framework. He articulated the demand for a nationalist identity that would cut across Hindu-Muslim differences in the Bengal province by encouraging political emphasis on certain narrative commonalities. These narrative commonalities for him, were formed through the sharing of inter-subjective communicative practices, particularly culture, language and society that made possible the existence of what I term, a historical aesthetic identity for the political collective regardless of their constituting individual religious identities. The idea of aesthetic identity that was working within Abul Hashim was an attempt to imagine a nation that would be both civic and ethnic at the same time.

This aesthetic idea of a united Bengali nation would be created on common ethnic lines and at the same time, commit itself fully to the universal ideals of a modern, secular nation-state. Hashim thought that this would counter the pressures of majoritarian politics and also defy the logic of viewing civic and ethnic identities as binaries and instead treat them as co-constitutive elements that together produce one kind of nationalist identity or character for a people. This tendency to synthesize two elements of a nation's political life can be seen in different stages of Hashim's life. We can divide his life into a political one and a religious one. Ultimately, Hashim wanted to help people think of these not as opposed binaries but opportunities for practical and intellectual co-habitation. Let me first take up Hashim's political trajectory through events that overlapped with his life and the larger political scenario.

Hashim and Politics

Abul Hashim came from a prominent political family in Burdwan (in West Bengal) where he grew up before moving to Calcutta as a young adult, to study law. His father Abul Kasem was a Congressman and had worked quite closely with one of the Congress founding members, Surendranath Banerjea. Kasem's participation in the Swadeshi (1905-11), Khilafat and Non-cooperation movements (1919-22) had left an indelible impression on young Hashim's mind who became interested in understanding the nature of social and political life in British India. Hashim's political debut came in 1936 when he participated in the Bengal Legislative Council, which was the upper house of the legislature of Bengal. In March 1940 he attended the Lahore conference held by the Muslim League where the All India Muslim League (AIML) party declared and passed for the first time a resolution stating that all Muslim majority provinces in British India should be allowed to become independent states. This became known as the Lahore Resolution.

At the conference, Bengal's then Prime Minister, Fazlul Huq who formally presented this resolution, emphasized that the resolution hopes to bring independence to all Muslim majority provinces in British India. Hashim later writes about the Lahore conference and Fazlul Huq's presentation of the Resolution as evidence of the nature of the relationship between the AIML and BMPL. The latter saw the AIML as an ally rather than a parent body and believed strongly that Bengal must be considered a distinct Muslim majority province that deserved to function as an autonomous unit in the event of independence. Huq was an enormously influential figure in Bengal's political history who served as Prime Minister of the province for six years and his political career, pre-independence, spanned over thirty years.

When Huq resigned from the Muslim League in March 1943, Khawaja Nazimuddin succeeded him as the premier of Bengal. Nazimuddin belonged to an aristocratic nawab family and much of his politics was shaped by his class position. Politically he was conservative and keen on a separate homeland for Muslims and subsequently became quite opposed to the United Bengal plan. His two-year term as premier of Bengal between 1943-45, were tumultuous and some political factions, even within the Muslim League in Bengal felt his politics was isolating the ordinary masses. H. S. Suhrawardy, who served as the last premier of Bengal undivided, before the province was partitioned at the time of independence, resented the Nazimuddin government and had his own political ambitions that led him to finally create an opposing faction against Nazimuddin within the Muslim League party.

Later on, in 1946 Suhrawardy led a successful political campaign and was elected the new Premier of Bengal. Suhrawardy was then able to encourage Hashim to play a more active role in the province's politics. In the years leading up to the legislative assembly elections of 1946, Suhrawardy encouraged Hashim to take on the task of reviving the Muslim League's image in the province as a more mass-based party, very much in touch with grass-root politics.

The Lahore Resolution in some ways could be seen as a prelude to a larger United Bengal scheme that emerged later on as it highlighted the possibilities of creating Muslim state(s) in the subcontinent. Hashim's approach to this possibility was not a consolidated religious nation-state but rather a nation state of Bengal, tied up by supra-community commitments, mainly bound by common language and cultural practices between Bengali Hindus and Bengali Muslims. For him, the Indian subcontinent represented the same thing as Europe, made up of autonomous sovereign units bound by a historically constructed idea of Europeanness. To Hashim, the Indian subcontinent and all its various composing units should strive for the same in their anti-colonial struggles.

Hashim and Religion

A key turning point in Hashim's life came in 1942 when he met a Gorakhpur-based theologian and philosopher Moulana Azad Subhani who at the time was working on reconstructing Islamic thought around the philosophical question of what it is to be human. Subhani introduced Hashim to the philosophy of 'Rabbaniyat' or Rabbanism'. The term is derived from the word Rab which refers to the grand architect, creator and sustainer of the universe. Rabbaniyat creates a phislophical route to engage with the idea of becoming a self through the divine ways of creation and evolution.

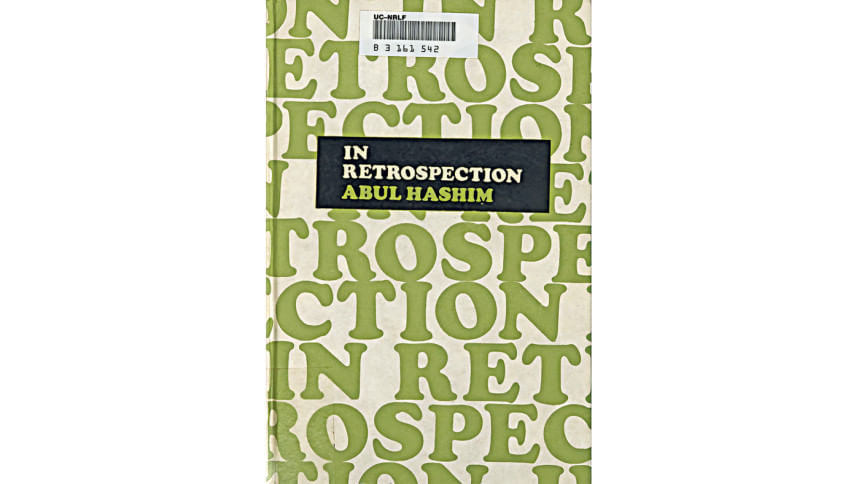

Hashim writes, "Rabbaniyat in concrete term means physical, mental, intellectual and spiritual development of man according to divine way of creation, sustenance and evolution of the universe visible in nature, in Al-Quran and in the life of the Holy Prophet Mohammad (peace be upon him). Al-Quran and the prophet did not teach a newfangled way of life but confirmed what was taught by other prophets, sages and philosophers of the world. 'Rabbaniyat' is the first principle of Islamic values.

'Rab' is the greatest attributive name of Allah and other attributes are contributory and complementary to this basic attribute. One who in theory and practice adopts 'Rabbaniyat' is called a 'Rabbani'. People talk glibly about Islamic state without the slightest idea as to what it actually means. A state which faithfully implements 'Rabbaniyat' in individual and collective life of the citizens is an Islamic State. Today, there is nowhere in the world a living Islamic social organism". (Abul Hashim, In Retrospection (Subarna Publishers, Dhaka, 1974, pp. 40–41)

Hashim saw Rabbaniyat also as a method to construct a cultural sense of religion that seems to be based on a moral understanding which emphasized the possibility of constructing the self through a kind of spiritual satiation that comes through religion but doesn't conform the individual to doctrines or tenets. It instead allows one to discover aesthetic symbols of community life and encourages the self to merge with the collective in a harmonious manner. This, he felt is attained through religion and not outside of it. He believed that in some ways this message was found universally in all religions. Hashim took great efforts in incorporating these views into his political life which subsequently started to resonate with a lot of young Muslims in the province who were eager to find a political voice for themselves.

This helped expand the membership of the Muslim League in Bengal and aided in its overall revival in the 1940s. There are delightful anecdotes in his autobiography about how enthusiastic these new members were in refurnishing and renovating the League office at No. 3 Wellesly [sic] lane, Calcutta which subsequently became an important place to plan the day-to-day political functioning of the party. For Hashim, and several other members like him, Dhaka and Calcutta were the two main political and cultural centres of the Bengal province.

Merging of Politics and Religion

In 1946, Hashim was fully invested in drawing up a plan for Bengal's post independent existence that would produce the least amount of violence and bypass the horrible fate of being partitioned. During Lord Wavell's last phase as Viceroy of India, it became quite clear that the AIML leadership and the Congress high command were unable to cooperate on several political decisions regarding independence- partition was going to be inevitable. Hashim found in Bengal Congress' Sarat Chandra Bose a sympathiser and someone who had become quite interested in the United Bengal Plan.

Towards the end of 1946, Hashim met Bose where he shared with him some of his ideas on the ideal kind of nation that would incorporate a multicultural ethos in its political sovereignty and imbibe a secular citizenship that wouldn't necessary be achieved through the bifurcation of state and religion but a co-constitution of the two. Bose who had earlier been sceptical of the Pakistan plan came around to Hashim's views on the necessity to save the province from being partitioned. Bose believed like Hashim, that India was a federation of different units and there was no reason for the province of Bengal to not demand complete autonomy.

This collaboration between Hashim and Bose led to the drafting of a formal proposal for a United Bengal that I have reproduced in my book. One of the clauses in the proposal was to have a system of joint electorates with reservation of seats proportionate to the population of Hindus and Muslims in the free state of Bengal. At the time of partition, the Bengal ministry would be dissolved and replaced with a new interim ministry with equal number of members from the two main religious groups. The Chief Minister would be a Muslim and the Home Minister a Hindu. Positions in military and administrative functions will be equally filled by Hindu and Muslim members.

The proposal failed to gain any support especially in the aftermath of the Calcutta Killings (August 1946) that locked the two communities into a state of hostility and mutual suspicion. The proposal also got no support from the Bengal Congress despite Sarat Bose's influence. Some within the Congress also saw partition as an opportunity to carve out a more prosperous western state with the industries in Asansol and Raniganj and also Calcutta with its port. The tussle for political power, the promise of economic prosperity and the sheer nature of political self-determinism against colonial rule all produced a sense of chaos and uncertainty.

In this chaos, the United Bengal plan should be seen as a symbol of cooperation and solidarity. But more than that it should be seen as an important attempt to treat ethnicity as something that can be defined beyond the scope of religion where one can actualise the sense of true belonging through shared commonalities. This for Hashim is a universal trait and in Bengal's case could be achieved through religion. Religious tenets must be made to commit themselves to the rule of law and most importantly to a sense of duty towards one's self in order to achieve a kind of spiritual becoming that ultimately dissolves the lines between individual and community.

In some sense Hashim's United Bengal plan was the political iteration of his deep philosophical understanding of what a nation truly ought to be. For Abul Hashim any new formulation of how a nation ought to take into consideration a new kind of public/political morality will have to seek to overcome narrow ethnic-religious prejudices and the myriad of problems associated with a society divided by both social and class inequalities. Through his life and work, Hashim worked to develop a possibility of reimagine the role of religion as an essential tool to truly liberate the human spirit.

Sucharita Sen is Associate Professor of politics at the Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JSLH), O.P. Jindal Global University (O.P. JGU), Haryana, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments