When Zainul Abedin left Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1947, as India and Pakistan negotiated a partition-ridden freedom from the British Empire, he was one of the city's most acclaimed artists. By the early 1940s, Abedin had become the youngest and beloved teacher at the Government School of Art. His stark sketches of hunger and death in the city's streets had captured the catastrophic, man-made Bengal famine of 1943, which was killing and displacing millions in Bengal, as the Allied army fought Japan on the eastern frontiers of the Second World War. His works fascinated artists, critics, journalists, activists, and a late-colonial public alike, who saw the very meaning of beauty and national form transformed in the artist's sharp, expressionistic realism.

In January and February 1945, Abedin featured on the cover of People's War, the national organ of the Communist Party of India (CPI) (Figure 1). His famine art was introduced in this issue by the party's iconic artist-cadre, Chittaprosad, as the CPI organised the first exhibition of Abedin's works. In 1944, Abedin had also illustrated the activist-journalist Ela Sen's Darkening Days: Being a Narrative of Famine-Stricken Bengal in May 1944. When the now-renowned artist Somnath Hore, then a young novice in the early 1940s, was identified by CPI leadership, he was placed under Abedin's mentorship at the art school in 1945. By 1946, Hore would begin his dedicated career of documenting popular resistance, experimenting with socially committed modernist art, and continuing, perhaps, Abedin's very own legacy in post-Partition, independent India.

Realism was a cornerstone in Abedin's art practice, as a vision and even as a conservatism that he would hold on to, while he dedicated himself to shaping artistic taste and pedagogy as Principal of Dhaka's art institute, formed earlier, in 1948-49.

Abedin's return to Dhaka, the capital of the eastern wing of a newly formed Pakistan, sprawled on both sides of India, was forced – even as he himself hailed from this former East Bengal's Mymensingh district. As Abedin, along with his fellow-artists from Calcutta – Safiuddin Amhad, Qamrul Hasan, and Anwarul Hasan – chose to leave a polarised, genocidal milieu of a communal riot-torn Calcutta, he had to confront deep professional and personal insecurity. Rebuilding artistic foundations in the new capital of Pakistan's eastern wing, Dhaka, was challenging.

Abedin would go on to become a foundational figure – an artist, pedagogue and cultural bureaucrat – central to the formation of an artistic sphere in East Pakistan, active also in the federal centre in the west. It took imagination, labour, and persistent negotiations with the federal government in West Pakistan. And even as East Pakistani artists like Abedin visited and thrived in the west, the asymmetries in artistic infrastructure between the two wings remained. Partition had marked the stories of artistic modernism in the sub-continent in ways lived and felt, but often invisible to history writing.

Zainul Abedin's artistic practice – from his early years as a migrant art school student in colonial Calcutta in the 1930s to his stature as Silpacharya – the most celebrated artist-pedagogue of post-liberation Bangladesh in the 1970s, carries these lived shadow-lines of 20th-century decolonisation in the sub-continent. Still more, and critically so, Abedin symbolises, along with his many other fellow artist-pedagogues across the decolonising worlds in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, this artistic legacy of shaping how freedom itself could be visualised in young nations undergoing often-turbulent postcolonial transitions. This allegorical weight that Abedin has had to shoulder – in life as much as in the afterlives of his legacy – has often also been heavy. Can we return to this heavy iconicity of a 'national artist', to draw his lines and lineages differently?

As a young entrant into Calcutta's art worlds in the 1930s, Abedin, along with fellow students from the Government School of Art, sought to generate new space for artistic realism. The art school's syllabus as well as the city's art discourse had been dominated hitherto by the idyllic "Indian-style" wash paintings of the Bengal School, pioneered in the early-1900s by Abanindranath Tagore, and institutionalised by his followers. In the 1930s, the Bengal School was still following idealistic mythological subjects and had partly morphed into a dynamic yet still-idealistic ruralist earthiness at Kala Bhavan, the art school of the experimental 'global' university of Visva-Bharati at rural Santiniketan, established in 1919 by Rabindranath Tagore. For Abedin and his fellow realist painters like Abani Sen or Gobardhan Ash, this idealism was inadequate to capture what contemporary society and landscape itself looked like. Against all odds, they would exhibit their works, and by the late-1930s critics were noticing. Reviewing their 1936 show, for instance, the critic Jaminikanta Sen had written that such works carried a new satyabodh – a "sensibility of truth" and a "new nationalism" that could visualise the nation via the harsh "truths of contemporary reality", marked by industrialisation, famished villagers, and their actual living conditions.

The famine pushed this realist sensibility to new extremes, as Abedin's art turned to a minimalist expressionism that transformed realism from the often-critiqued sterility of academic naturalist "colonial" style art, to a dynamic yet challenging form of modernist realism that questioned the very foundation of artistic truth and beauty. Abedin's famished rural refugees in Calcutta's street corners, battling crows and dogs for morsels of food were more than an index of art's social commitment or the art of the famine – they were, indeed, the aesthetics of late-imperialism and the paradoxes of anti-fascist war in imperial colonies of the Allied army itself. As Abedin, then an impoverished migrant artist himself, drew his ink sketches of hunger-ridden pavements, with dry brush and ink on cheap brown wrapping paper, walking these streets on his way to the art school, a new shape of artistic roles in the shadow of empire, was emerging. He himself probed these possibilities, as he joined the Anti-Fascist Writers' and Artists' Association, and other collectives of progressive art already in the early 1940s, steered increasingly by a cultural movement shaped by the Communist Party of India.

Realism was born in the streets of Calcutta, the noted art critic of postcolonial Bangladesh, Burhanuddin Khan Jahangir would write of Abedin's famine works, in his biography of Zainul Abedin in the 1990s. Abedin's famine drawings were to stay with him all along his post-1947 career in East Pakistan, exhibited in his shows as he travelled across the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and held close as he fled an invading Pakistani army during the liberation war in 1971 that gave birth, through another genocide, to today's Bangladesh from East Pakistan. Realism was a cornerstone in Abedin's art practice, as a vision and even as a conservatism that he would hold on to, while he dedicated himself to shaping artistic taste and pedagogy as Principal of Dhaka's art institute, formed earlier, in 1948-49. Yet Abedin's realism carried many lines, as it shaped what the social – and via that, the political – could mean in art. From the 1930s itself, this sense of the social, for Abedin, was heavily mediated by rural lives – whether in his early forays into painting rural labour in 1930s Dumka, or the rural displaced in the wartime famine, or increasingly in post-independence East Pakistan, the unchanging rhythms of a rural everyday, between struggle and resilience, labour and leisure.

There is in Abedin's practice, a dialogue between the rural and the social, and modernist form-making itself that would inform his pedagogy and legacy – and indeed, its allegorical weight for East Pakistan and Bangladesh that he carried as Silpacharya. This same dialogue also shapes Abedin's significance our understanding of how integrating (social) realism with modernism, and the figurative with the abstract, were critical cornerstones in the artistic imaginations of the decolonial transformations of the 1940s-80s. This has implications for pushing art historical thinking beyond the artificial oppositions between figurative and abstract art planted globally by an Americanised art discourse via the cultural politics of the Cold War.

Abedin himself was a postcolonial traveller in this global cultural Cold War. By the mid-1950s, he was a highly mobile artist travelling across the USA, Europe, the Middle East, Central and East Asia, the Soviet Union, on various fellowships like the Commonwealth, the Rockefeller grants, and on commissions from the Pakistani government. In September 1951, he made his first trip to London on a Commonwealth scholarship to study art pedagogy. Abedin studied at the Slade School and exhibited across London. In 1952, he attended the UNESCO conference held during the Venice Biennale, where ideas of cultural freedom, artistic exchange, new aesthetic standards of modern art and post-1945 cultural reconstruction were being discussed. In the 1960s, Abedin was invited by the Soviet Union where he was awarded a gold medal, and later by the Arab League to visit and sketch the Palestinian guerrillas and refugees. He was, in fact, a typical, artist-diplomat of the period of decolonisation and Cold War who would be serially invited by the United States and the Soviet Union, countries of the Eastern Bloc as well as Japan in a muted contest over the cultural imagination of the 'Third World'.

Abedin's journeys marked his artistic trajectory in the styles he experimented with, though his subjects remained the same – labour, struggle, and the rural everyday. For instance, after he returned from his first spell in the UK, Europe, and Turkey between 1952-53, his style would change, though mildly and for a short span. He began experimenting in linear simplifications, breaking up the image, trying out semi-Cubistic figurations, while remaining committed to building art's foundations in a public culture. Throughout the 1950s, Abedin made conscious efforts to integrate art with the people – whether in projecting the image of the common man in art or promoting public access and participation in art-making. Over the 1960s, Abedin tied himself more to the collection and documentation of folk art, a substantial part of which formed the core of the Sonargaon museum in post-liberation Bangladesh. This was, at the same time, his self-fashioning as a patron and preserver of folk art, and also increasingly, his retreat into the identity of a pedagogue rather than that of a modernist artist.

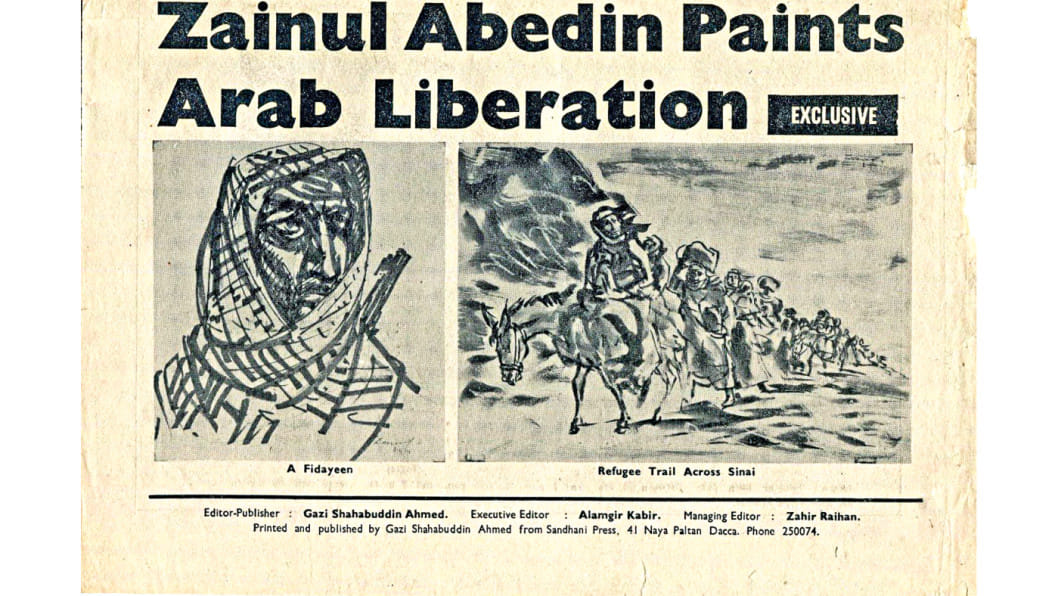

1970 appears as a culmination of Abedin's artistic trajectory. In spring he made the scroll Nabanna, a celebration of the harvest festival where he created what can be seen as an allegory of the incipient nation – from the displacements of the 1940s, through growing rhythms of everydayness, to labour and leisure that have built the social fabric of his nation. In the summer of 1970, Abedin visited Palestinian refugee camps along the Jordan river as part of his tour across the Arab world (Figure 2). He wanted to head back, and organise another exhibition, the profits of which he intended to donate to the Palestinian cause. He was unable to return, and the works he left behind in Cairo were also lost. Returning to Dhaka in that summer, Abedin was to be overtaken by a growing political resistance at home, one that would lead to a genocidal liberation war, giving birth to Bangladesh. In November 1970 when the tidal wave in Monpura killed and ravaged millions, Abedin toured the destruction on a helicopter and returned with notes. Much later, he would paint Monpura '70 – as his wife Jahanara Abedin noted – in one sitting, with rapid movements.

Monpura'70 (Figure 3) is a harking back to the famine of 1943, as much as an encounter with the immensity of death, once again in the shadow of liberation struggle. So was Nabanna at the start of 1970. The Palestinian experience sits in the middle as a radical return to art's encounter with displacement, a battle itself perhaps, with the demand of artistic form in the shadow of dehumanisation. The dialectical tension between art's formal and socio-political pulls both shines and challenges how this aesthetics of 20th century decolonisation could be understood. Abedin the artist, his epic scrolls, his persisting returns to a rebel bull or rural fragments of labour and repose stand as possibilities – to read art as archives for understanding how the historical time of 20th century decolonisation was lived, imagined, remembered, and challenged, despite the ways our individual nation-states narrate fragmented pasts.

Sanjukta Sunderason is an Associate Professor of Art History at the Department of Arts and Culture, University of Amsterdam.

Comments