Australian involvement in the Bangladesh Liberation War

If you think about the international reaction to the Bangladesh Liberation War, you most likely would consider the United States government openly siding with Pakistan. The People's Republic of China, Sri Lanka, and the Arab world also aligned that country. Many western nations – such as the United Kingdom – remained neutral in what they considered a civil conflict rather than a war of secession.

Apart from India and the USSR, it seemed that the Bangladesh liberation movement had few allies. My recently published book, Citizen-Driven Humanitarianism and the Bangladesh Liberation War: Australian Aid during the 1971 Refugee Crisis, presents a different picture. In this book I show that when we look beyond the official stance of the Australian government and consider the perspectives of ordinary citizens, we find a populace deeply affected by Bangladeshis' struggle for freedom.

When Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman proclaimed the independence of Bangladesh 53 years ago, Australian newspapers immediately ran front page articles on the declaration. From the beginning, Australian newspapers described in detail the violence of the Pakistani army and the repressive nature of West Pakistani rule.

On 29 March 1971, broadsheet The Age (Australia's newspaper of record), reported on the brutality of the early days of the war, repeating the claim by the Press Trust of India that the Pakistani military had killed more than 10,000 people, including civilians, in just two days. By reporting the war in such terms, Australian journalists laid the groundwork for Australian citizens to understand the conflict through the frame of Pakistani suppression of Bangladeshi demands for independence.

In its 29 March editorial, The Age stated that East Pakistan was a 'besieged province', 'confronted by military forces far stronger' than its own, and therefore had no choice but to declare independence and abandon its legitimate claims for greater regional autonomy. Interestingly, The Age foreshadowed the unlikelihood of a political solution to the conflict. The editor wrote: 'A nation cannot be held together indefinitely by the military repression of a hostile majority of people. To the existing differences of race, custom, language and geography will be added an insuperable barrier of hatred and resentment.'

Within days of the onset of hostilities then, Australians were informed not only of the tragic events unfolding in Bangladesh but also understood the origins of the conflict and why Bangladeshis wanted their freedom.

Australian humanitarian responses

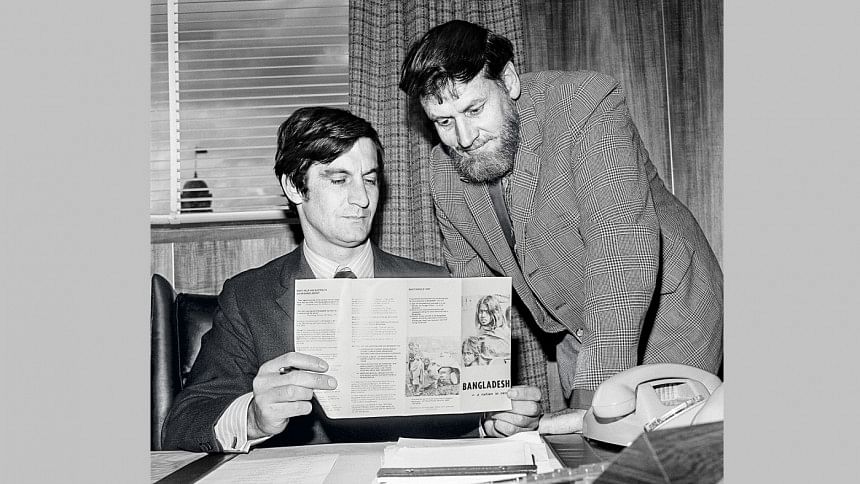

My research explores how and why Australian citizens provided humanitarian relief to Bangladeshi refugees in India. While the responses of governments are important, they can never tell the whole story. Indeed, Australian aid to Bangladeshi refugees is an example of civil society leading government action. Typically, one would assume that governments lead the people. During the 1971 Liberation War, the opposite was true as citizens influenced government policies, not just on aid but also on the formal recognition of Bangladesh as an independent state.

In essence, my book is about how citizens and non-government organisations (NGOs) mobilised, fundraised, and distributed aid in a region far from their homes and to individuals with whom they had little in common. Through my research, I found Australians from a cross-section of society who were outraged at the extent of human suffering in the refugee camps, appalled by the injustice of Yahya's military rule and believed that poverty was completely avoidable, if states chose to alleviate it.

My book includes chapters on the aid activities of an array of humanitarian agencies. Chapters cover the activities of the international Red Cross, transnational Christian agencies, and grassroots organisations such as the Freedom from Hunger Campaign.

It is important to note that in 1971, the Australian humanitarian NGO landscape was an over-crowded market. Each organisation competed for brand recognition, prestige, access to political power, and of course, donor dollars. We naturally think of humanitarian NGOs as benign actors. However, my book shows the extent of competition within the sector as they attempted to gain market dominance and outdo one another.

Citizen humanitarianism: an untold history

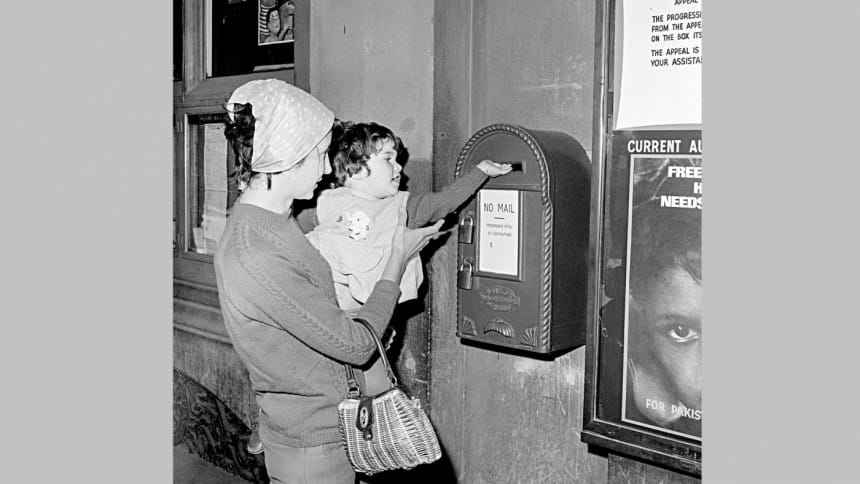

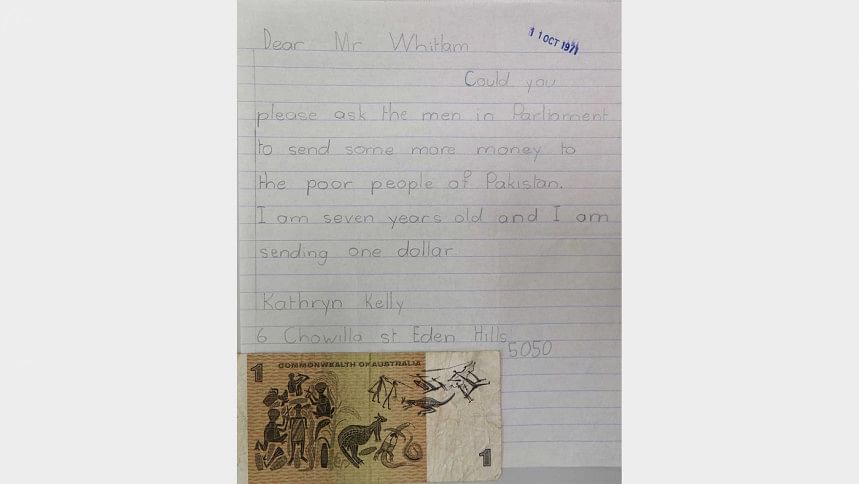

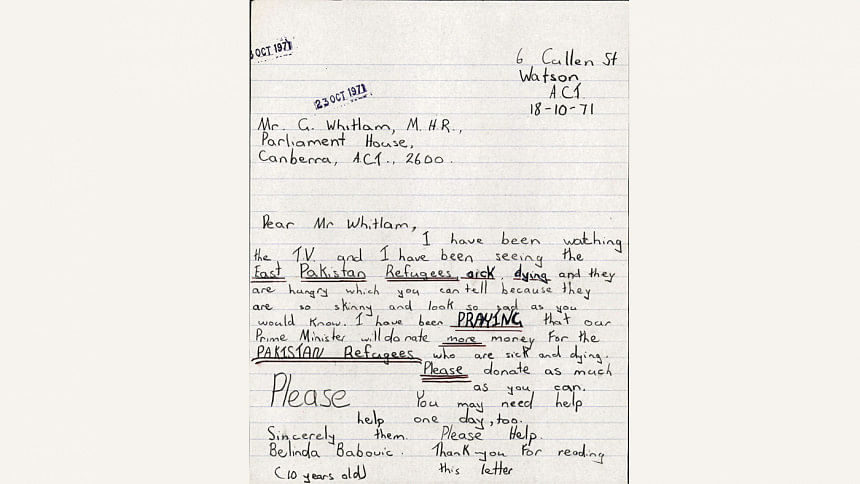

The final chapter of my book explores humanitarian actions of individuals. This includes a comprehensive analysis of over 2,500 letters written by Australian citizen to their politicians urging the government to give more aid. These letters are a rare find in the National Archives of Australia (NAA) and provide valuable new insights into how Australians of all backgrounds understood the conflict in Bangladesh and how they thought they could help. I found myself particularly moved by letters written by children, even though they were ineligible to vote.

Here are two examples:

Less than one month into the conflict, 11-year-old Vicki O'Meara from a middle-class suburb in Melbourne wrote:

Dear Sir,

I know A$10,000,000 [US$85 million in today's money] is a lot of money but I think you could spare it for the poor Pakistan refugees. If all the people in Australia were starving, then I don't think you'd have much trouble in finding the $10,000,000. It's just that they are a long way away from us and it is hard for us to imagine what it would be like. Please hurry and send the $10,000,000 quickly before it is too late and there will not be any cause because the refugees will all be dead.

What I value in the letters penned by children is that they avoid clichés, are blunt, and usually show a sophisticated understanding of global issues well beyond their years.

In this second example, 10-year-old Belinda Babovic wrote to Opposition Leader (and later Prime Minister) Gough Whitlam from a working-class suburb in Canberra, the nation's capital. In the letter, Belinda wrote in pencil and sparsely used pen for emphasis on particular words. Here, Belinda reveals the importance of television and visual imagery in helping her understand the scale of the refugee crisis. She also discloses that she has been praying for the Australian prime minister to donate more money. The role of news media and religious conviction were repeatedly cited by many Australians in their letters to political leaders.

Hunger strikes

Aside from writing to politicians, citizens also engaged in public performances that inspired onlookers to learn more about the Bangladesh liberation movement in general and the suffering of refugees in particular. For example, Indonesian-born poet Paul Poernomo staged an extended hunger strike on the steps of the Melbourne General Post Office to draw attention to the starvation faced by Bangladeshi refugees. As the weeks rolled on, passers-by gave coins to his donation tin, money that was then forwarded on to the Freedom from Hunger Campaign, which had aid distribution staff working in the West Bengal refugee camps.

The 36-year-old Poernomo took his hunger strike (along with a ragtag of followers) to Canberra. Poernomo fasted for two weeks, this time on the steps of Parliament House. He attracted the attention of politicians and journalists, both of whom promoted and broadcast Poernomo's cause to the nation at large.

After a short stint in hospital due to extreme dehydration, Poernomo continued his fasting tour around the country. He staged his final hunger strike outside the Sydney General Post Office. As in Melbourne, passers-by donated money to support refugee relief activities.

The impacts of Poernomo's hunger strike were far-reaching. At a minimum, Poernomo single-handedly raised A$50,000 for the Freedom from Hunger Campaign, making 1971 its most successful year to date. Beyond donations, Poernomo inspired thousands of citizens to lobby their political representatives, urging the Australian government to do more for Bangladeshi refugees and officially support Bangladeshi independence.

Individual activism

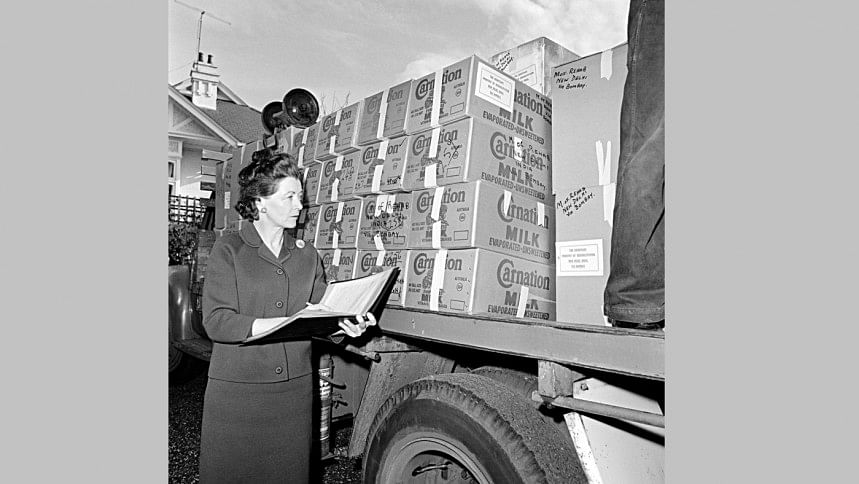

Paul Poernomo was not the only example of an Australian going to extreme lengths to help Bangladeshis. Melbourne upper-class housewife and Catholic humanitarian, Moira Dynon, had a long history of donating powdered and condensed milk to India throughout the 1960s. When the Bhola cyclone hit in 1970, she turned her attention to East Pakistan. Her humanitarian activities increased again when war broke out in 1971. Unlike large, international NGOs, Dynon was an advocate of person-to-person humanitarianism. By focusing on friendship, goodwill and cooperation, Dynon stressed the importance of personal relationships. She believed that every individual could, and should, make a difference to ease avoidable suffering.

Dynon also proved to be a tireless worker, willing to travel great distances to spread her message. Throughout 1971, Dynon engaged in a speaking tour across Australia, educating Australians on the history and politics of Bangladesh, and why its people demanded independence from Pakistan. She urged her audience to donate money and goods to her small aid agency, which was then forwarded to the West Bengal Council of Women for distribution in the refugee camps.

Broader significance

The examples listed above may seem insignificant on their own. But what they shows is that collectively individual actions can shape public opinion, which then has the capacity to change government policy. In the case of Australia during the Bangladesh Liberation War, the actions of individuals helped push risk-averse politicians to take a moral stand that was at odds with its main ally, the United States. Within the space of 10 months, Australian government policy moved from declared neutrality to supporting openly Bangladeshi independence, even if that meant attracting retaliation from Pakistan and the ire of America. Australian government aid was also increased on five occasions, again in response to public pressure. It is important to note that private aid (that is, donations from Australian citizens) far outstripped government assistance.

From the Australian perspective, the lessons of this event in history are two-fold: one, it provides a rare example of people leading the government, rather than the other way around. It is an inspiring tale of individuals taking action, which had ripple effects throughout Australian society. Two, it shows that Australians educated themselves on the events unfolding in Bangladesh, rather than blindly following the Cold War logic of the United States, which pitted capitalist Pakistan against socialist Bangladesh. This episode reveals Australians as deeply engaged with their Indian Ocean neighbours and committed to creating a just world free from persecution and oppression. I can only hope that Australians and Bangladeshis will remain good neighbours as they confront the complex challenges of the twenty-first century.

Rachel Stevens is a Lecturer in History at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University in Melbourne.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments