Cartographic Imagination and Colonial Landscape Paintings in and around Bengal

Cartography in India might have had its roots in this expansionist ambition but went on to achieve much more than this. Rennell's Map of Hindostan, published by an act of Parliament in 1782, inaugurated the cartographic identity of modern India for the first time on the world stage. It geographically integrated the eastern entrepot all the way to the Himalayan hinterlands and the north western Punjab-Sind, reorienting existing land into a fresh geo territorial unit heavily dependent on its eastern delta for overseas commerce. This is not to say that this outlying terrain was unexplored for exactly these reasons. Earlier regimes and powers, both local and foreign, had their stakes all over the Bengal littoral region, making it one of the most coveted and strategic locations in the world for a very long time. However, it was the British East India Company which was responsible for the territorial transformation of the region as the fulcrum of power.

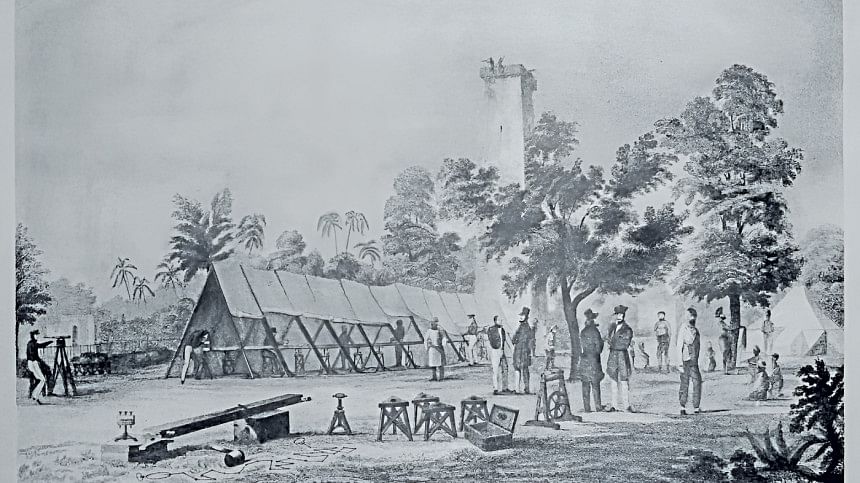

With James Rennell's surveying operations surging outwards across India while being focalized in Calcutta, large parts of India which were thus far outside the scope of the colonial information grid were fast brought under detailed observation. The utility of a panoptic knowledge of routes that was sought from the administrative class was stressed by Rennell in his book, A Description of the Roads in Bengal and Bahar (1788). Rennell lists four major centers, Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna, and Dacca: "the first being the seat of government, and the others either the capital military stations, or factories or both." Since the grant of the Dewani to the English East India Company by the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II in 1765, the seat of power shifted from Murshidabad to Calcutta, which now needed to be connected with all major stations throughout the region. The British colonial regime, with its growth of mercantile capital, commercial manufacture, and a drive towards the monetization of social relations, transformed the existing circulatory practices. The decline in commerce and attrition of urban centers in the early phase of British colonization of India was therefore generally seen as a breakdown of an earlier circulatory regime. Many of the arguments foregrounding the importance of transport infrastructure, roadways, navigation, and later on the railways in British India, were based on this foresight of bringing products and capital into a disciplined and efficient system of circulation.

Cartographic practices were not limited to academic mapping alone. Pictorial representations flourished in abundance as riverine landscape paintings became a popular medium to portray journeys into the subcontinent. William Hodges and the Daniells were major forerunners in initiating the genre, making landscape paintings popular and lucrative for later European traveling artists to participate. From the late eighteenth century onwards, many amateur artists in the East India Company's service explored innumerable opportunities to record the sights of India. Among the most productive of amateur artists in India was probably Sir Charles D'Oyly (1781-1845). Son of a senior Company official, John Hadley D'Oyly, the Company's Resident to the Nawab Babar 'Ali at Murshidabad, Charles was educated in England from where he returned to India in 1797. He held minor posts in the Company at the beginning of his career but gradually rose to higher and more responsible positions in the service. His first major appointment was as Collector of Dacca from 1808 to 1812. Following this, he returned to Calcutta, first as Deputy Collector and then Collector of Government Customs and Town Duties, a post he held until 1821 when he was appointed Opium Agent in Patna. D'Oyly's specific aesthetics are infused with geographical knowledge. In his movement away from riverine landscapes into the mofussils and hinterlands, his art can be seen as depicting 'spatial stories,' which link together, draw itineraries, and hence organize places as though in a map. Be it his paintings of Calcutta, Dacca, or Gyah or his monumental work titled Sketches of the New Road in a Journey from Calcutta to Gyah (1830), a project undertaken on the occasion of the inauguration of a new military road linking the Grand Trunk Road to Calcutta, his drawings contextualise the new colonial circulation evolving from existing routes. His topographic drawings are a kind of spatial practice which narrativise the fresh emergence of space, supplanting the space and network of the ancien regime. D'Oyly's The Sketches of the New Road celebrated the initiation of the idea of geographical improvement and mobility as the signpost of British triumph. The areas surveyed by the artist's eye were brought under cartographic surveillance and military order. The Sketches simulated an ideal tour through a coherent visual experience. In this series, D'Oyly adopted the European style of the 'prospect,' by then a widely accepted format, for his panoramic views. A bird's eye view of an entire terrain, the style could include with fields, forests, roads and rivers, sometimes towns and cities, travelers on the road, tiny as against the scenic landscape. The road interlaced with semaphore towers, as it were, paved the way to India's modern future.

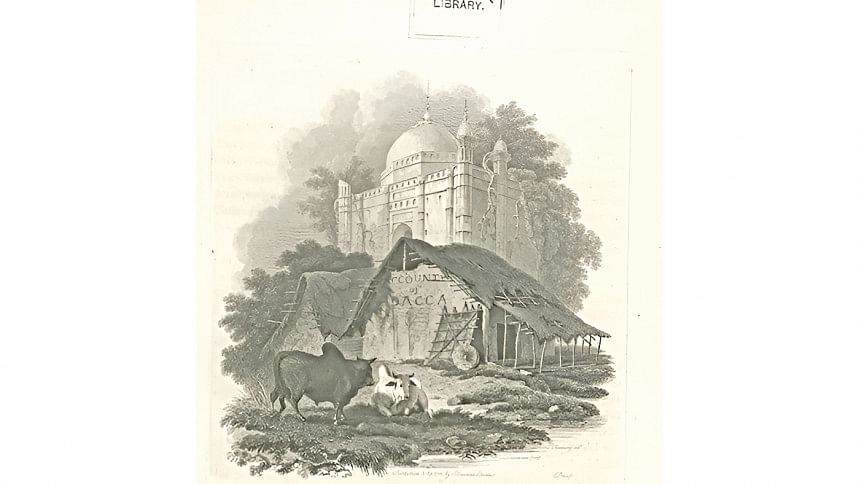

The Dacca paintings share a similar format with the Calcutta paintings and capture mofussil life in its plebeian detail. Most depict Mughal architecture then in ruins, hovering atop dense oppressive vegetation taking root in it, exuding a sense of decadence and a passing away of an old order. Also depicted are roads, rivers, and nullahs (streams) fallen into disuse.

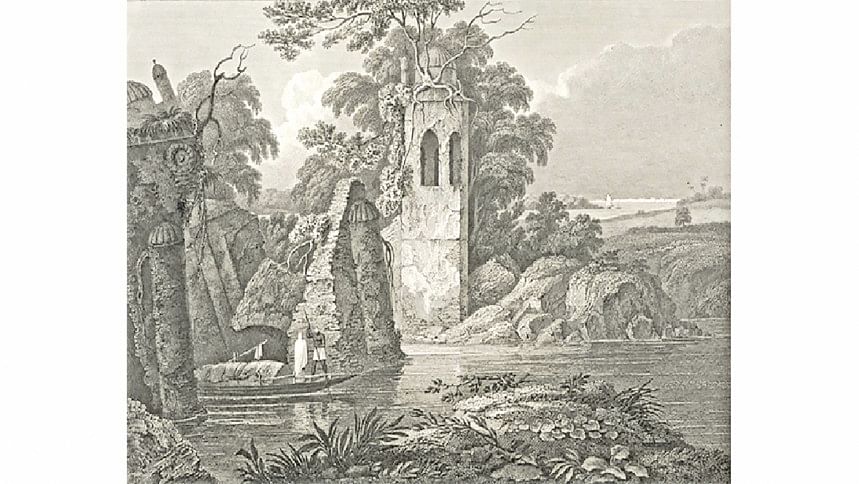

In Views of Calcutta and its Environs, D'Oyly ventured away from the banks of the Ganges into the black town in search of local experiences: the streets, bazaars, huts, rituals, fairs, and festivals of the locals. In 1808, when he was appointed Collector of Dacca, he promised Warren Hastings that he would offer "as companions a few of the ruins of the city of Dacca which […] are exquisite for their magnificence and elegance and are calculated to tempt the pencil of an artist." The result was the drawings for Antiquities of Dacca (1830), planned as a joint venture with another professional artist, George Chinnery (1774-1852). His sketches and paintings dealing with Dacca were brought out from 1823 onwards in the form of folios from London. Each of these folios had about four to five sketches or paintings in it together with topical and historical descriptions of them. These brief explanatory notes were submitted by an acclaimed historian, Persian scholar, and artist, Military Surgeon James Atkinson (1780-1852). The roping together of image and accompanying explanatory letterpress was a relatively established convention at the time. D'Oyly granted greater significance to the vernacular and public architecture of an erstwhile important port township. He insisted on replacing the established hierarchical distinction between places, largely through preceding artistic ventures of Hodges and the Daniells, with a more fundamental equivalence. The Dacca paintings share a similar format with the Calcutta paintings and capture mofussil life in its plebeian detail. Most depict Mughal architecture then in ruins, hovering atop dense oppressive vegetation taking root in it, exuding a sense of decadence and a passing away of an old order. Also depicted are roads, rivers, and nullahs (streams) fallen into disuse.

D'Oyly starts off by recalling the strategic location of Dacca not only because it had once been the capital of Bengal, which rose to pre-eminence during the time of Aurangzeb, but also because of the presence of other European powers prior to the coming of the British and the East India Company:

Long before the English settled at Dacca, the Dutch had established a factory there, and transacted their business through native agents; [...] The English factory at Dacca, having been preceded by that which Tavernier terms "a tolerably good one", was rebuilt about a century ago by Mr. Stark, with the permission of Iltizam Khan, [...] previous to which native agents had been employed to purchase cloths, and convey them for sale to Calcutta. It was not till the year 1742 that the French succeeded in getting permission to rebuild a factory here, which is now, as well as that erected by the Dutch, a heap of ruins.

In both his Dacca and Behar paintings, D'Oyly reinforces his identity as an administrative officer in the colonial service by commenting on the state of decay and administrative lapse the regions had suffered in the recent past. The Antiquities deal with descriptions and depictions mainly of the architectural past and present, and there is inevitably an attempt to draw comparisons between past elegance and the poverty-stricken present.

Thus Ducca for more than half a century was the capital of Bengal, and continued to be enriched by the multitudes which crowded to the courts of its governors. The stupendous remains of gateways, roads, bridges, and other public works, which present themselves on every side, sufficiently prove the former grandeur and magnificence of the city.

While correcting earlier records such as that by the French traveller, Tavernier, D'Oyly takes credit for his own 'discovery', his detailed research and production of original knowledge:

It would appear from this account by Tavernier, that almost the whole of Dacca at that time consisted of habitations built of mud, straw, wood, matting, and bamboo, such as are constructed by the common people at present. He mentions no public buildings excepting those of the Europeans; although the Great Kuttra, a most magnificent edifice, as well as the Mosque of Syuff Khan, had been erected many years before, and the small Kuttra more recently; but still several years before the celebrated French traveller visited Ducca. These splendid buildings, as well as several others, seem to have eluded the observation, or escaped the memory of Tavernier.

While D'Oyly takes pride in exhibiting his discoveries through his drawings, he does not miss an opportunity to point out existing flaws in the survey of a representative of a rival European power, namely the French. In a move that marked the age, he disentangles what he sees from what is already known. When he mentions the Daniells and their inability to identify the picturesque significance of the location, he simply flaunts his artistic vision to complete an unfinished agenda – to reveal in sight an entire terrain which had been left out for so long.

From Chinnery's drawings, he finally chose only three that contrasted "present poverty with Mohammedan importance, and rusticity with architectural elegance" and explicitly commented on the decline of Dacca. The work ends with a high romanticist note contemplating on the passage of time, the fall of empires, and the vicissitudes of life and human endeavors:

To the noise of mariners and shipwrights which once resounded along the nulla – to the bustle and pomp of commerce and princely equipage – has succeeded a degree of loneliness and silence. [...] The bridge before us is fast following its predecessors [...] Though now mutilated and mouldering under the effects of time and neglect, and the ruder dilapidations of war, it is still an interesting object to the eye of the landscape painter and poet.

Such comments establish connections between the medieval and the modern, nature and industry, to the detriment of the latter. The ruined mill of an earlier colonizing power proved purposeful in establishing a continuum, granting a timeless quality to the scene and the place. The seemingly romantic statement obliquely refers to the failure and falling apart of the earlier system of mobility and circulation, thereby suggesting the possibility of repair by a stronger force. This idea is reiterated in a number of his paintings in the series, such as in depictions of collapsed bridges such as the 'Paugla pool'. A picturesque scene could be granted a sublime status if it could nobly inspire the artist with elevated thoughts.

Topographic representations framed by philosophical and sentimental utterances reaffirmed the sublime prospect of the place, reflecting that cartographic amassment of geographic space was not wholly incongruous with the aesthetic predilections of the day.

Nilanjana Mukherjee serves as a Professor in the Department of English at Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi, and holds the position of Joint Secretary at the India International Society of Eighteenth Century Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments