More than a century ago, revered Bengali writer Begum Rokeya in her short story Sultana's Dream had visualized futuristic inventions like solar cookers, atmospheric water generators and flying air-cars. She dreamt of Ladyland as a feminist utopia without crime, the death penalty and epidemics. Here men were shut indoors and responsible for childcare and household chores, while women with "quicker" brains pursued science and shaped inventions.

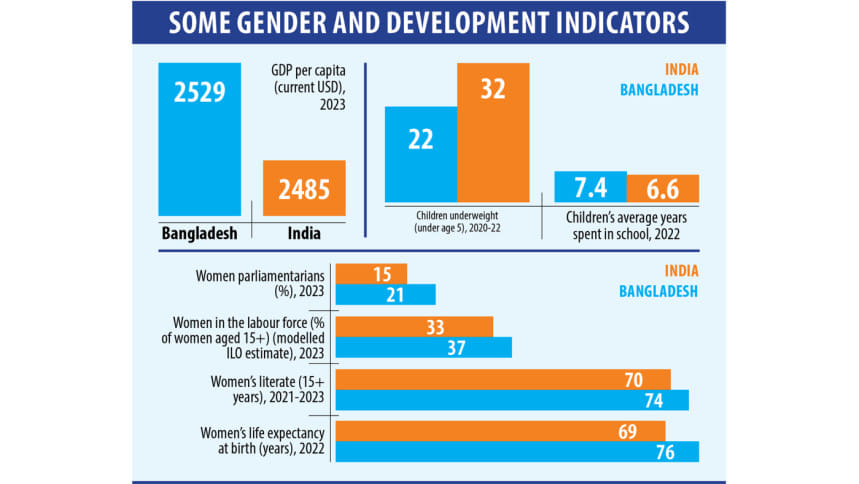

Five decades after its creation, modern Bangladesh does not resemble Sultana's Dream. But despite all its recent political turmoil, for the last quarter of a century, Bangladesh has had only female heads of state. On average, Bangladeshi women are also more likely to live longer, work outside the home and hold seats in Parliament compared to Indian women across the border. Bangladeshi children are less likely to be underweight and usually spend more years in school.

Bangladeshi women ahead

My five-year doctoral research aimed to probe precisely this puzzle of the rapid progress in the quality of healthcare, education and life chances in Bangladesh and other Indian neighbours, such as Nepal and Sri Lanka. My book 'Unequal: Why India Lags Behind Its Neighbours' was based on this cross-border fieldwork.

Unfortunately, India's focus in the last few decades has largely been only on rapid—and lopsided—economic growth. With rising inequality, extreme contradictions of caste, class and gender have worsened one another. Patriarchy is so acute that gender discrimination begins even before birth. Forty-six million women are 'missing' from India's population, especially due to sex-selective abortion in the last four decades. Ironically, educated women from wealthier households and the upper castes are more likely to abort female fetuses. Even as adults, one of every four women in India cannot read and three do not earn an income. Their dependence on men is so extreme that few rural women get a chance to flourish outside the confines of the four walls of their kitchens or homes.

Bangladesh has been able to dilute its social inequalities of gender, class and caste gradually over centuries. Three catalysts have fuelled its progressive transformations—the investment in public services, the influence of social movements and the unleashing of women's agency.

In contrast, consistently more than a third of Bangladeshi women work outside the home. Unlike India, it is also culturally more acceptable for Bangladeshi women to be employed even after marriage, provided they can find jobs. Teaching, for example, is a largely feminized profession. In Bangladeshi government schools, female teachers have a 50 per cent quota. After clearing the public examinations, teachers undergo 18 months of training, with 1-year on-the-job within school classrooms. In one school, we met many teacher trainees wearing either pink saris or burkhas as uniforms. Unlike India, teachers also receive their permanent postings nearer their homes and transfers are rare, especially to aid women teachers.

Bangladeshi women also work regularly on factory shop floors. Every morning, on any Bangladeshi rural highway, streams of women in cotton saris can be seen walking purposefully towards these factories with steel dabba lunch boxes in their hands. These economic opportunities have also helped women to renegotiate their control over public spaces. Outside a rural jute mill, at a roadside tea stall, I even saw several women workers in saris, with their hair covered with the thin cotton pallu, who were busy sipping tea and eating shingaras (samosas) and cake. Most of them worked in the jute factory, often on night shifts, unthinkable across the border in the north Indian heartland.

Catalysts of Change

Bangladesh has been able to dilute its social inequalities of gender, class and caste gradually over centuries. Three catalysts have fuelled its progressive transformations—the investment in public services, the influence of social movements and the unleashing of women's agency.

First, Bangladesh has been a trailblazer in the doorstep delivery of welfare services, from healthcare to micro-credit, which not only empowers women but also employs them as teachers, health workers and social workers. That apart, government initiatives such as the Female Secondary Stipend Program have been so effective that across classrooms there are often more girls than boys.

Interestingly, similar to most high-achieving countries, many social sector programs are integrated to exploit synergies. School children, for example, are included in hygiene education, such as hand washing demonstrations and health education. They are also encouraged to complete their vaccinations and periodic de-worming to improve nutrition. Community participation is another key. A school teacher told me that in 2005, a decade before India's Swacch Bharat Abhiyan, there was a competition among the North Bangladeshi districts to be 100% open defecation-free. Teams of teachers, local government officials, elected representatives and even Muslim clerics travelled door-to-door to motivate families to build toilets. Community-led total sanitation (CLTS) and regular group discussions also ensured that rural Bangladeshis were made aware of the ills of using the great outdoors.

Second, in Bangladesh, socio-political, peasant, labour, religious, and women's movements that have cumulatively, over long decades and even centuries, altered social hierarchies.

For example, in Panchagarh district, I saw archaeological excavations underway in the ancient sixth-century Bhitorgarh fort, which have unearthed Buddhist stupas, temples and viharas built along the Silk Route. East Bengal, as a part of the ancient Pala and Chandra empires, had more than one millennium of egalitarian Buddhist influence before the advent of syncretic Islam. So, even before the mass conversion of the population to Islam in the thirteenth century, East Bengal has long had fewer caste-style disparities.

East Bengal's also has a rich history of subaltern peasant movements across centuries. From the Sannyasi and Fakir rebellions (1763–1800) to the Faraizi movement (1818–62) and Tebhaga Andolan (1946-47), peasant revolts with varying degrees of success, have been crucial in gradually diluting class hierarchies. In particular, in the fifties and sixties, the Language movement was important in extending an equalizing influence across religions to promote Bengali culture.

My research also traces how class hierarchies shrank after three unique historical waves of elite displacement. After the 1905, 1947 and 1971 partitions, the Hindu zamindari and bhadralok classes largely shifted to India and the Urdu-speaking elite to Pakistan. So, rural Bangladeshis who have been left behind have fewer social divisions among them. Most Muslim village women we met in our door-to-door survey had no idea about their surnames, bongsha (family) or jati (clan) name. Especially after the 1974 famine, a unique social contract developed between the Bangladeshi ruling classes of all hues and ordinary citizens to prioritise welfare services. As political sociologist Naomi Hossain argues, all regimes knew that if they did not deliver, they could easily be replaced in a country with legendary street protests.

Lastly, Bangladesh's unique history has also unleashed women's agency. The nine-month Liberation War marked a turning point in altering gender relations. The Mukti Bahini guerilla soldiers in the 1971 Liberation War even had a separate female battalion, the gun-carrying 'Naari Muktijoddhas' (female freedom) fighters. But, the Pakistani army employed mass rapes as a weapon of war. This was one of the darkest chapters in the history of the 1971 Liberation War. As veteran feminist Raunaq Jahan has described, the impact of this social tragedy led to 'the beginnings of a feminist consciousness in the country'. It 'unhinged women's role from being necessarily protected by men, to go out to earn an income'.

The famine in 1974 marked another turning point. As feminist economist Naila Kabeer has described, this resulted in women renegotiating the old 'patriarchal bargain' and breaking purdah norms which confined them to the home.

So, women's employment in Bangladeshi factory shop floors and school classrooms has taken decades to fructify.

The Right to Equality

The visionary 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights upheld the ideal that, "all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights." Among developed countries, citizens in more equal societies, tend to have better health, education, child development and gender equality. Bangladesh also offers valuable lessons on this front.

India, as the largest democracy in the world, too, can experience transformative progress in the lives of citizens if inter-generational inequalities of caste and class are smelted with socio-political transformations. Equality between men and women is also equally important.

Of course, within India there are vast differences between the North and the South. In 2020, a newborn girl in the southern state of Kerala could expect to live to the ripe age of 78 years—two years more than Bangladeshi women. At the same time, girls born in the north Indian states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh are likely to survive an entire decade less.

Begum Rokeya in one of her essays on the 'Degradation of Women' thunders, "Women [also] hold the key to society's success, because unless the Indian women awake, India cannot rise".

A century later, her words still ring true. Indians too need to dream about Ladyland.

Swati Narayan is an Associate Professor at the School for Public Health and Human Development at O.P. Jindal Global University. She is the author of Unequal: Why India Lags Behind Its Neighbours

Comments