Anwarul Quadir (1887-1948) was a key literary figure whose work significantly influenced the intellectual movement of Bengali Muslims in late colonial Bengal. He is best known for completing the novel Abdullah after the death of its original author, Kazi Imdadul Huq (1882-1926). Abdullah is recognized as a pioneering work in Bengali literature by Bengali Muslim writers, addressing several contentious social issues. Additionally, Quadir published his only essay collection, Amader Dukkho, in 1934, which compiled his writings from various periodicals. Now 90 years old, this seminal book addressed pressing issues of its time that remain relevant today.

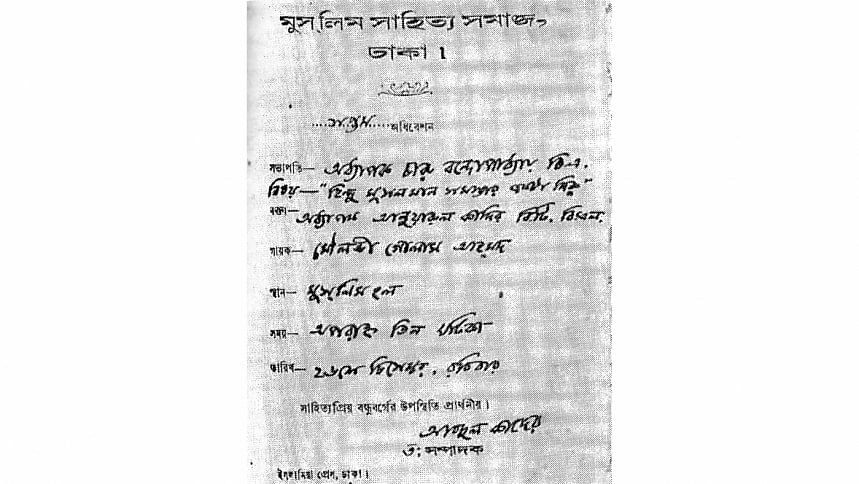

Born in 1887 in Port Blair, Andaman Islands, as his father was posted there as a headmaster of a government school, Anwarul Quadir held the family title of Kazi, and their family originally hailed from the village of Paygram Kasba in Khulna. He completed his entrance exam at Jessore Zilla School and earned his BA from Presidency College. Quadir pursued a career in teaching and obtained his MA in English Literature in 1928. He also served as an assistant to Mr. Steplan, who was specially assigned to the proposed Dhaka University. Quadir passed away from cancer in 1948 at Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta. He was awarded the title of Khan Sahib for his lifelong service in education. Anisuzzaman noted that Quadir was an ideal figure among his students and colleagues, with his significant contributions to the formation and operation of the Muslim Sahitya Samaj being highly valued.

Anwarul Quadir was the senior-most author among the seven key writers of the Muslim Sahitya Samaj, which is better known as Shikha Gosthi, with their publication Shikha, the leading progressive writers' association of Bengali Muslims in Dacca at the time. This association played a crucial role in awakening the newly educated minds among Bengali Muslims, injecting a fresh literary and intellectual spirit into the stagnant society of East Bengal's main city.

Mustafa Nur-Ul Islam described Dhaka during the emergence of the Shikha Gosthi and the free intellect movement, popularly known as the Buddhir Mukti Andolan:

"At the top is the Nawab family of Dacca, an impregnable fortress of conservatism. Dacca, in that period, was far removed from the modernity of free liberal thought. A university was just being established on the outskirts of Ramna Green and the Dacca Inter area, and Jagannath College was located near Sadarghat in the main town. In this limited and often hostile environment, a small group of individuals championed the cause of 'free intellect,' founded institutions, and published periodicals. Remarkably, most of these young reformers were from outside Dacca and lacked significant local support or patronage."

Historians note that after C.R. Das's death in 1925, communal tensions intensified in Bengal, with Dhaka frequently witnessing Hindu-Muslim riots. Amid this volatile atmosphere, the group introduced a new vision in Dhaka. As the most senior writer in the group, Anwarul Quadir believed it was not just the responsibility of political leaders but also of writers and thinkers to guide the nation in the right direction.

Although poet Kazi Nazrul Islam was not directly involved with the Dhaka-based literary association, he was invited to its inaugural conference in 1927 due to his prominence among young Muslim intellectuals in Bengal. He traveled from Kolkata to open the conference and expressed his enthusiasm with these words:

"Today, I am thrilled to make a joyous announcement at this conference. For the first time in a long while, I enjoyed a peaceful night's sleep. I see that a new movement among Muslims has begun here, and I intend to spread this message far and wide. Furthermore, I once thought I was the only heretic, but now I am convinced that virtuous individuals like Maulavi Anwarul Quadir are the true dissenters. My circle of supporters has expanded; beyond this solace, I seek nothing more."

Nazrul was inspired by the new association's activities and lauded Anwarul Quadir as a leading thinker within the group. With a hint of sarcasm, he called both himself and Quadir "Kafir" or "infidels" to underscore their challenge to traditional views.

As noted earlier, a significant contribution of Anwarul Quadir was completing the novel Abdullah. He wrote chapters 31 to 41 based on the original draft, and the complete version was published in 1932. Kazi Abdul Wadud remarked on their differing styles:

"Kazi Imdadul Haque is primarily a painter, whereas Anwarul Quadir is more of a psychologist, a difference reflected in their writing styles. Notably, Quadir's contributions shine in two chapters: one depicting Saleha's death and the other describing Mir Sahib's final days. While Imdadul Haque portrays Saleha as nearly lifeless, overly constrained by her father's rigid principles, Quadir introduces a touch of compassion to her character and adds a hint of novelty and affection to Abdullah's otherwise mundane life."

Wadud notes that Anwarul Quadir brought a more dynamic and humanistic dimension to Saleha, the lead female character, who was largely passive in Kazi Imdadul Haque's original portrayal.

Anwarul Quadir's another major contribution is Amader Dukkho, an essay collection. Originally published in Calcutta, the prose work was reprinted twice, first in 1990 and again in 2010.

The title Amader Dukkho (Our Sorrows) underscores the urgent issues Anwarul Quadir critically examined during his time. This period was marked by intense and unresolved Hindu-Muslim conflicts, which eventually led to the Partition of Bengal. Quadir noted that leaders of these competing groups adopted narrow, self-serving views driven by religious biases, failing to unite for the nation's benefit. The government officials were more concerned with their own positions and perks, with their salaries rising while the common people's suffering worsened.

He presented a critical analysis of the socio-economic and political climate, which was increasingly polarized between Hindus and Muslims. This growing distrust approached a state of near-separation, with each side accusing the other of grievances. Quadir found Hindu accusations of Muslims destroying temples and desecrating idols to be largely exaggerated, just as he saw Muslim fears that Hindus would eliminate them after achieving independence as overstated.

Quadir argued that both Hindus and Muslims faced significant poverty and criticized inherent issues within each community. He found the Hindu caste system incompatible with modern democratic values and noted that Muslims were often more conservative and resistant to change, sometimes practicing their religion in a way that seemed bigoted and misaligned with Islam's core principles. Instead of focusing on religious differences, Quadir emphasized shared problems like severe poverty, food shortages, and inadequate clothing. He questioned whether the country's leaders would understand these issues or continue to follow antagonistic policies.

Nazrul was inspired by the new association's activities and lauded Anwarul Quadir as a leading thinker within the group. With a hint of sarcasm, he called both himself and Quadir "Kafir" or "infidels" to underscore their challenge to traditional views.

Anwarul Quadir's lecture, titled "Bangli Musalmaner Samajik Galad" ("The Social Faults of Bengali Muslims"), appeared in the first issue of Shikha and was later included in his book Amader Dukkho. In this lecture, Quadir explored the challenges and potential of Bengali Muslims. He emphasized, "Without the liberation of the mind, religion cannot be taught. Intelligence is essential for understanding and following religious principles. The true essence of Dharma has been lost due to a lack of intelligence, leading to a dominance of orthodoxy in our practice."

In the essay collection, Quadir also critiqued the thinking of influential educational and social leaders, such as the respected chemist and educationist Prafulla Chandra Ray (1861-1944). Ray remarked that the narrowness of the Hindu caste system had driven lower-caste people to seek refuge in the "kindheartedness of Islam," resulting in over 50 percent of Bengal's population becoming Muslim, which he perceived as a misfortune for India. Quadir questioned how a slight majority of Bengal seeking refuge in the "kindheartedness of Islam" led to the wreckage of the entire country. He believed Ray might have been trying to provoke Hindus into rejecting the caste system. However, Quadir doubted that divisions wouldn't have developed within Hinduism if people hadn't embraced Islam. He argued that the rise of Buddhism and many other sub-sects of Hinduism indicated that oppressed people would have embraced any other sect or religion, even if Islam had not arrived in this land.

Quadir questioned how this shift towards Islam could be blamed for the country's problems, arguing that Ray might have been trying to provoke Hindus into reform but ultimately failed to address the deeper issues. He suggested that divisions within Hinduism would have arisen even without Islam's influence, as evidenced by the rise of Buddhism and various Hindu sects among oppressed people.

He dismissed Ray's conclusion as narrow-minded, arguing that such sectarian blame emerges under subjugation and reflects a form of subservience. He emphasized that if even a respected social leader like P.C. Ray, known for his liberal ideas and acceptance among Muslims, held such views, it would alienate Muslims and lead them to seek a fictitious identity elsewhere, neglecting their place in their own land. He suggested that overcoming such narrow-mindedness requires insight and a fresh perspective, avoiding stereotypical thinking in a colonized state.

Quadir did not accept that communal issues in India began with the colonial period but pointed to historical examples, such as the exile of 500 Brahmins during Harshabardhan's reign for causing unrest. He believed that widespread communal issues arose from rulers seeking personal benefits, with religion frequently manipulated for these purposes. He criticized the hypocrisy of showcasing religion, which obscured sincere and humble adherence to its practices.

During the final phase of colonial Bengal, the Hindu-Muslim feud intensified as economic opportunities dwindled. Zamindari became less profitable, agriculture stagnated, and competition between the two major religions centered on the limited number of government jobs. These rivalries extended beyond daily economic and social activities and even impacted Bengali literature, where communal biases influenced the portrayal of characters in religious terms. Quadir criticized this environment, claiming it was impossible to produce "honest literature" under such conditions, and expressed hope that literary figures would develop a more harmonious approach in their work.

Quadir argued that both communal Hindus and Muslims had failed to adopt Tagore's ideals of compassion and love, resulting in a lack of empathy and leaving the nation's problems unresolved.

Quadir emphasized Rabindranath Tagore's view on the Hindu-Muslim issue, noting Tagore's concern that the nation's identity had become mired in religious divisions, obstructing the path to unity. Quadir argued that both communal Hindus and Muslims had failed to adopt Tagore's ideals of compassion and love, resulting in a lack of empathy and leaving the nation's problems unresolved.

Tagore's predictions about the fallout from Hindu-Muslim rivalry are echoed in the account of scientist Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda (1900-1977). During a trip to Darjeeling in the late 1920s, the young Qudrat-i-Khuda met Tagore by chance. In their conversation about socio-political issues, Tagore voiced his concern that ongoing Hindu-Muslim conflicts would thwart any efforts at unity, ultimately leading to the creation of separate states for Hindus and Muslims.

Remarkably, Tagore appeared to anticipate the partition of Bengal as early as the late 1920s, noting the increasing tensions between the major communities. Quadir found parallels between Tagore's observations and his own insights. Furthermore, Tagore, after reading the novel Abdullah, expressed his pleasure, mentioning that it deepened his understanding of the inner lives of Muslims in Bengal and shed light on various social issues.

Although Quadir's discussions were framed within the context of undivided Bengal, the issues he highlighted have continued and frequently intensified into serious conflicts even after the formation of three separate states. The sorrow expressed in Amader Dukkho remains relevant in a subcontinent still grappling with communal divisions.

Priyam Pritim Paul is a Researcher and Journalist at The Daily Star.

Comments