Growth of National Consciousness

Although the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent and sovereign state is a fact of recent history, this country has been the home of an ancient civilization. From very early times human species belonging to various races and tribes and coming from different regions had been pouring into this land and had settled here permanently. To mention only few, there were proto-Australoid, Mongoloid. Aryan or Indo-Aryan, and Scythians. They had brought with them their own varied cultural traits. These were intermingled with the indigenous cultural elements of this region and by this process the culture of Bengal was invigorated and transformed through the ages.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century Bengal was conquered by a band of Turko-Afghan horde who were followers of Islam. Before Muslim conquest, however, between the middle of eighth and twelfth centuries, for nearly four hundred years, Bengal was under the rule of the Kings of the Pala dynasty. The Palas were Buddhists. Thereafter a ruling dynasty from the South Indian region known as the Senas established their supremacy in Bengal. The Sena rulers were zealous Hindus. In order to establish the Brahmanical religion firmly in this land a considerable number of Brahman pandits well-versed in Hindu religious scriptures were brought to Bengal during this period and were settled in this country. But traditional Hinduism did not gain firm foothold in Bengal. Till the time of Muslim conquest at the beginning of the thirteenth century the influence of tantrik Buddhist elements which represented a corrupt form of Buddhism could be noticeable in the religious life of the common people of this region. The comparatively easy manner in which the Turkish military adventurer Ikhtiyaruddin Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji was able to subdue Bengal with a handful of soldiers was due to the fact that Hinduism did not have strong social roots in this country.

It is generally believed that Islam had come to Bengal long before the Muslim conquest of the region in the thirteenth century. Some Arab Muslim traders who had come to Bengal around eighth and ninth centuries are said to have established settlements in the coastal regions of Bengal particularly in Noakhali and Chittagong regions.

The Muslim conquest of Bengal in the thirteenth century facilitated the spread of Islam. People particularly belonging to the lower social orders who had been suffering from the evils of the Hindu caste system and other prejudices readily accepted Islam being drawn by its simple religious creed and egalitarian social system. But despite conversion to an alien religion they did not forsake their indigenous culture.

It is commonly known that the inhabitants of Bengal have sprung from varied racial background. Besides Dravidian, Aryan, Arab, and Turko-Afghan elements there was another element which came from East Africa. For quite a number of years Bengal was ruled by five or six Abyssinian sultans. There was also a practice of keeping Abyssinian guards at royal palaces. Traces of this Abyssinian descent are still noticeable in the facial features of both Bengali Hindus and Muslims. Again, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the coastal areas of Bengal were infested by Portuguese-Arakanese pirates known as Maghs. Traces of this element can also be found in the physical appearances of some inhabitants of the coastal region.

According to the famous sixteenth century Mughal historian Abul Fazl the name Bangal or Bangla was derived by suffixing the word al to Banga or Vanga which was the ancient name of the major part of this region. The word al meant not only the boundary of farm-land; it also meant embankment. The low lands of this region had so many of these als that this land Banga eventually came to be known as Bangala or Bengal or Bangladesh that is, the country of Bangala.

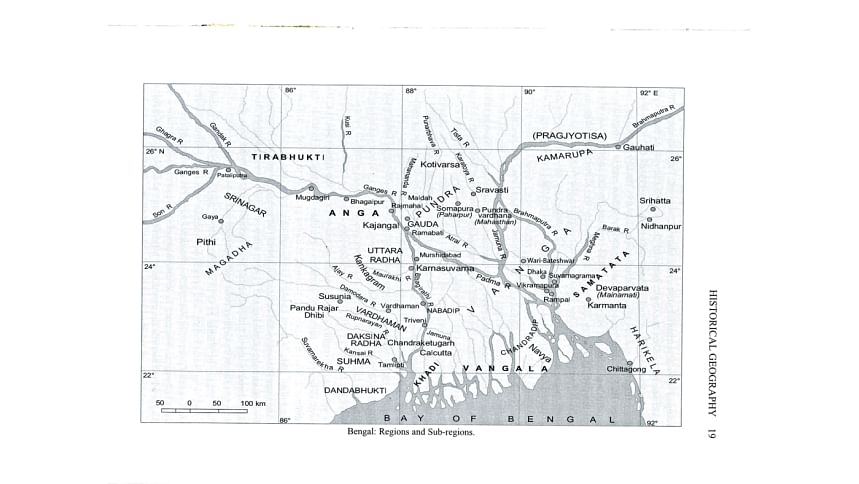

In ancient times Bengal was divided into a number of human settlements. Each settlement grew up with people belonging to a particular clan. Generally each settlement carried the name of the clan which settled there. for instance, Banga or Vanga, Gauda, Pundra and Rarha. Without going into further details it may be said that by eleventh century A.D. there was an independent settlement which was known as "Bangala and whose eastern frontier was the river Bhagirathi, that is the southern part of the Ganges. At that time the country of Bangala embraced the whole of Eastern and the coastal region of Southern Bengal. This area roughly coincided with the present territory of Bangladesh. It may, however, be said with some certainty that the efforts made by king Sasanka in the seventh century and the subsequent rulers of the Pala and Sena dynasties to bring the whole region of Bengal under the unified supremacy of Gauda had not succeeded. It was only during the middle of the fourteenth century that the independent Pathan/Afghan Sultan Shams-uddin Iliyas Shah had been able to conquer almost the whole of this region of Bengal and unite it under one rule. Subsequently, during the time of the Mughal emperor Akbar Bengal became a province of the Mughal empire and was known as 'Subah Bangala.

There are certain particular traits in the way of life and culture of the Bengali people which have marked them out as a distinct nation. The Bengalis have always been an emotional people. In the words of Rabindranath Tagore "the call from the heart and from humanity would get easy response from here. And the same may be said about the religion of this land. The people of Bengal have been drawn more by the inner spirit of religion than by its outward external rituals. Hence, narrow communal feeling could never influence the minds of the people of this region. Tagore had truly observed: "Even in ancient times humanist Bengal was looked down upon by the upholders of traditional society and scriptures of India. Anyone visiting this land for purpose other than pilgrimage had to perform penance.

That means Bengal has always been free from the orthodoxy of scriptures. Such unorthodox religious orders like those of Buddhists and Jains always held sway over Bengal and its neighboring regions. At that time the land of Magadha (Bihar) along with Bengal was also treated as outcast and was independent. The same independent spirit is also noticeable among the Vaishnavas and bauls of Bengal. They have never allowed their literature and songs to be overburdened by ornamental or scriptural influence. Free from the great weight of scripture and yet how deep and noble is their expression. Our spiritual saints have in the simple language of their devotional songs such as kirtan, baul and bhatiyali created such incomparable humanistic feelings, sweetness and charm that one cannot reach their depth nor can one surpass their limit. Where can you find the limit or the end of such unbounded human emotion? Like the unchained spirit it is so simple and free from all burdens: its mystery is limitless and boundless.

If we review the history of the preaching of Islam in Bengal we would find that the activities of the unorthodox sufi saints, pir-dervishes, aul-bauls have been far more effective than those of the orthodox and fundamentalist mullahs. These spiritual saints had by their moral qualities and unblemished character been able to win the respect and admiration of all sections of people. The religious tradition which they had initiated was that of spiritual humanism and tolerance which have left an everlasting imprint on the Bengali mind and intellect. In our cultural tradition also the predominant trend has been not of discord or conflict but that of peaceful co-existence of different faiths and the harmonious blending of various creeds. In fact, the characteristic feature of Bengali life and culture is unity in diversity. Before the advent of British colonial rule communal antagonism as we know it today did not exist either in Bengal or in other regions of the Indian subcontinent. For various historical reasons communal antagonism or religious conflict began to manifest during British rule. It would appear that through their struggle for liberation the Bengalis were able to resurrect their age-old tradition.

The world to-day is divided into many nation states. Nationalism is the basis of the modern state system. In one sense modern nationalism may be compared with religion. As in the past religion had served as a driving force which had united people of all classes under one banner, so in modern times particularly after the French Revolution the new idea of nationalism seemed to be the most inspiring doctrine of all which welded together diverse sections of people. In fact, the roots of many wars in modern times may be traced to nationalism.

Although the idea of nationalism had been germinating for the past several centuries, it was only after the first world war particularly at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 that nationalism gained universal recognition. It was at this great conference that the principle of self-determination of each nation was for the first time declared unanimously. This declaration was reiterated in much more stronger language by the charter adopted by the United Nations after the second world war. It is however one thing to proclaim an ideal and quite another to implement it. As Hans Kohn has observed:

Nationalism is first and foremost a state of mind, an act of consciousness, which since the French Revolution has become more and more common to mankind.

The present day Bangali nationalism has grown out of a collective feeling of oneness among the people irrespective of their caste and creed inhabiting the geographical territory now comprising Bangladesh. This feeling or consciousness has after 1947 assumed new dimension and character and forms the basis of the new nationalism of Bangladesh

Nationalism is primarily a territorial concept. It is the collective consciousness or feeling of a people inhabiting within the boundaries of a particular geographical territory. This consciousness or feeling is caused by several factors. In Europe during the period which is known in history as the Middle Ages which lasted for nearly thousand years —from fifth to fifteenth centuries —every aspect of a man's life —polities, society, art, literature and philosophy—was dominated by religion. In those days states were created on the basis of religion. Hence those who held political power did not hesitate to exploit the religious faith and prejudice of the people in order to maintain themselves in power.

Various factors contribute to the growth of national consciousness among the people of a particular region such as race, religion and language. But the rise of modern nationalism is not caused by any single factor. For example, take the case of religion. It is true that throughout the ages religion has succeeded in unifying large sections of mankind; but such unification solely on the basis of religion has not lasted long. The overriding influence of religion, however, has greatly declined owing to economic, social and political changes and the development of science and technology as well as improvement in the means of production. Most religions are not confined within particular geographical limits for instance Christianity and Islam are spread over many parts of the world. In the Middle Ages attempts had been made to unify Christendom and the Islamic world under the Holy Roman Empire and Caliphate, but this is not possible at all in modern times. Thus we find that both Christian and Muslim worlds are divided into so many nation states.

Like religion, language also by itself cannot be the basis of nationalism although both religion and language can largely help in awakening national consciousness. The inhabitants of Arabia and north Africa though they all speak Arabic and are adherents of Islam have not been able to from a single nation state.

The most essential feature for the growth of national consciousness is the awareness of a common inheritance. Without this awareness national feeling or consciousness cannot fully develop notwithstanding the fact that a particular group of people may belong to the same race or religion or speak the same language or live in the same region or are inhabitants of the same state. According to the famous nineteenth century French historian and philosopher Ernest Renan (1823-1892):

A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which are really one, constitute this soul, this spiritual principle. One is the past, the other is the present. One is the possession in common of a rich inheritance of memories. The other is the present consent, the desire to live together, the will to realize the unimpaired heritage.

A particular community's collective memory of the joys and sorrows of its past days, its consciousness of a glorious inheritance of its distinct way of life in defense of which its innumerable members have fought, have made sacrifices or have laid down their lives — these are the factors that contribute to the making of a nation

Since nationalism is primarily a territorial concept one of its principal sources is unalloyed love for the territory, that is, patriotism. And with this sentiment there arises a common sense of identity among all the people irrespective of religion, caste and color that inhabit the territory. Hence, nationalism is invariably linked with secularism.

In this context we can have a somewhat clear idea about the nature of nationalism in Bangladesh. Not many years ago, the Bengali Muslims had viewed their image and cultural identity from two opposite angles. Should they identify themselves as Bengalis or Muslims? This was the question which had deeply agitated their minds. In seeking answer to this question some had sought to merge their Indigenous Bengali identity into the all-embracing whirlpool of Islam, while others attempted to establish their Bengali identity by completely ignoring the contribution and influence of Islam. Again, there were some individuals who viewed the situation differently at different times.

Although myth is not history, myth may help in making history. Thus Pakistan was created on the basis of a myth. The Muslims of India had come to believe without any historical foundation or logic that since they adhered to one common religious faith namely Islam, they belonged to a distinct nation and possessed a distinct culture of their own. Hence they expected that their hopes and aspirations would be fulfilled if they could establish a distinct state of their own. This was the prime idea behind the Pakistan movement. Between 1940 and 1946 a great majority of the Indian Muslim community seems to have been overtaken by this psychosis. Of course the general Hindu attitude of indifference if not hostility towards the Muslim community and caste prejudices of the Hindus also contributed in a great measure to the growth of Muslim separatist feeling and anti-Hindu communalism particularly among the rising generations of the Bengali Muslim middle classes.

The creation by Pakistan would not have been possible without the support of the Bengali Muslims. They were the most vocal champions of the Pakistan movement. In fact, the Bengali Muslims constituted more than half of the Muslim population of India. But soon after the creation of Pakistan the Bengali Muslims began to be concerned regarding their future within the framework of the Pakistan state which came to be dominated by non-Bengali Muslims mostly Punjabis and Urdu-speaking immigrants from India. These elements began to exploit the resources of the Eastern region of Pakistan solely for their own benefit. No serious attempt was made to develop the Bengali speaking region. The Bengali Muslims particularly resented the conspiracy of the Pakistani rulers to make Urdu as the state language of Pakistan disregarding the feeling of the Bengalis who were very much proud of their language and cultural heritage. In fact, the Bangali Muslims were now in an introspective mood. They were passing through a period of groping with regard to their cultural identity. So long they were emotionally drawn more towards the events in the Muslim world outside India than to their own country. In the changed situation after the creation of Pakistan, the Bangali Muslims drawn by patriotic feeling were beginning to be aware of their distinct cultural identity. It is in this context that the great Bengali Muslim linguist and scholar and a distinguished exponent of Islamic learning Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah made a remarkable observation:

It is a reality that we are Hindus and Muslims, but the greater reality is that we are all Bengalis. It is not the question of any ideal, it is a basic fact. Mother nature has in her own hand imprinted such indelible marks of Bengaliness on our face and language that these cannot be hidden by outward signs of thread or tuft on head [worn by orthodox Hindus] or cap-lungi-beard (worn by Muslims).

Out of this awareness was born in course of time the new distinct Bangali nationalism. This nationalism was new in the sense that it was different from the communal nationalism that had existed due to certain peculiar historical situation in pre-1947 India. The present day Bangali nationalism has grown out of a collective feeling of oneness among the people irrespective of their caste and creed inhabiting the geographical territory now comprising Bangladesh. This feeling or consciousness has after 1947 assumed new dimension and character and forms the basis of the new nationalism of Bangladesh. The people of this region after the creation of Pakistan were in the changed perspective beginning to be conscious of their distinct cultural heritage —a heritage which was not limited within the narrow bounds of any particular religion but a heritage which was composite and humanist in character; and this consciousness of common heritage had led to the creation of the independent and sovereign Bangladesh state.

In order to have a clear understanding of the historical background of Bangladesh nationalism it would be necessary to analyze the changes that had taken [place] in the social and political thinking of the Bengali Muslims during the nineteenth century.

This article is the first chapter of the book Bengali Nationalism and the Emergence of Bangladesh: An Introductory Outline (International Centre for Bengal Studies, 1994).

AF Salahuddin Ahmed (1924-2014) was a renowned historian, and a national professor of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments