Kabar at 70

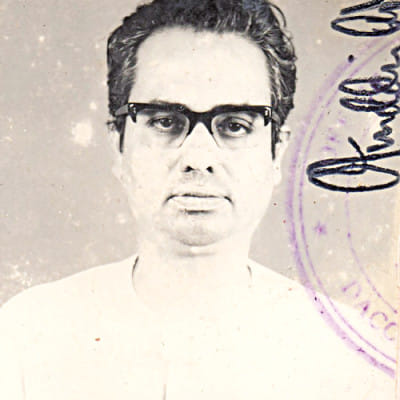

Born in a respectable middle-class Muslim family and holder of an Intermediate of Science degree from the Aligarh Muslim University, Munier Chowdhury (1925–1971) was growing up as a fashionable young gentleman with an Islamic worldview till his involvement with Anti-Fascist Writers and Artists Union in 1943, while he was still a student at the University of Dhaka. He had already found fame as a playwright by the time he passed his MA in 1947. During the turbulent days of communal violence which spread like wild fire in 1947, he is known to have risked his own life by trying to save the lives of many minority Hindus in Dhaka city in East Bengal (what now is Bangladesh). By that time, he was a member of the Communist Party. Actively involved in the Language Movement, Munier Chowdhury served his first term of imprisonment in 1949 because of his involvement with the Communist Party. He obtained his freedom by promising to disassociate himself from politics. He joined the Department of English, University of Dhaka in 1950 and in the next year, had acted in a play and directed another. He was arrested again in 1952, on 26 February, along with two other university teachers. While in prison, he wrote Kabar (The Grave), a play in one act, which, as Chowdhury himself acknowledges, bears strong influence of Irwin Shaw's Bury the Dead (1936), and in many ways the play foretells his and his motherland's future.

Kabar is set in a graveyard, late at night. It opens with the Leader, who, as we gradually come to know, is very influential and placed high in the political hierarchy. Hafiz, a police officer who is completely faithful to the ruling party and the government, joins him a little later. Both have been drinking to overcome fear – the Leader openly from bottles that he has brought while Hafiz has been helping himself stealthily from the bottles of the Leader. Their interaction generates wry humour as it exposes a horrific background: a number of people were shot brutally by the police in the preceding afternoon and the two are at the graveyard to supervise the burial of the dead before the public comes to know the actual number and create further trouble. Hafiz reports to the Leader that he has skilfully pacified the grave-diggers who had earlier refused to bury the dead without a proper funeral. However, Murda Fakir, a lunatic mendicant who has been living in the graveyard since all members of his family died in the famine of 1943, intervened to cause hindrance. Continuing to drink, the Leader advises Hafiz to bury Fakir as well.

By that time, Murda Fakir has silently entered the scene like a ghost. The Leader panics when he becomes aware of Fakir's presence but Hafiz tries to put up a brave front and attempts to pacify him. Ringing an eerie note, Murda Fakir declares that he knows the odour of the dead and it is they (i.e., the Leader and Hafiz) who smell of the dead, not those for whom the grave is being prepared. He exits to call the dead to rise, asking the two to take their place instead. When he leaves, Hafiz congratulates himself for 'successfully' dealing with a lunatic. However, the two have hardly a moment of relief when in a surrealistic haunting scene, the dead actually arise, refusing to be buried. When the political leader fails to convince them to return to their graves, the faithful police officer turns resourceful and comes up with a brilliant ploy. He play-acts as the mother of one of the dead and the wife of another, and emotionally pleads that they should sleep. When they appear to be nearly convinced, Murda Fakir arrives to lead the dead out in a procession. By then, it is dawn and the ghosts appear to have melted in the first rays of sunlight. One of the guards on duty appears to inform the Leader that their job of burial has been completed. The Leader and Hafiz are much relieved – for the rising of the dead was 'only' a nightmare, a hallucination under intoxication in a graveyard.

If a defining moment can indeed be identified as to when the Bengali nation began to be narrated in the theatrical context of the people belonging to the landmass now identified as Bangladesh, perhaps the performance of Kabar by Munier Chowdhury on 21st February 1953, can contend most strongly. The performance, an early example of 'prison theatre' undertaken entirely by the prisoners and for the prisoners, was held clandestinely to commemorate a rare moment in the history of humankind, that had erupted on 21st February 1952, when the people of East Bengal sacrificed their lives for the recognition of their mother tongue as the state language.

The entire process of writing and performing the play is no lees significant in the history of theatre in Bangladesh. It was the winter of 1952–53. Munier Chowdhury had set himself to writing Kabar in a cell (known as the 'Dewani') in the Dhaka Central Jail, where he was imprisoned along with 15-20 other political prisoners including Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Before this, he had received a clandestine note from Ranesh Dasgupta (an eminent litterateur and journalist), who was imprisoned in a larger cell (known as 'No. 2') along with 60-70 political prisoners. In the note, Ranesh Dasgupta urged Munier Chowdhury to write a play, which the imprisoned members of the Communist Party would perform in their cell (No. 2) on the night of 21 February, to commemorate the bloodbath of 1952. The play, Ranesh Dasgupta had instructed, was to be such that it would be possible to (i) present it after 10 in the late evening, when it was mandatory to put out the lights; (ii) execute lighting of the performance with eight to ten hurricane lanterns, to be borrowed from the student-prisoners of the cell (who were given the lanterns to continue their studies beyond the lights-out time); and (iii) perform all the female characters by the male inmates.

Munier Chowdhury fulfilled all the conditions and completed the play—Kabar—on 17 January 1953. As he indicates in the stage directions given at the very beginning, he turned the constraining physical conditions of the prison into his favour by weaving the action of the play around the very conditions. Instead of performing Kabar in bright light, it was played in a terrifying, mysterious, and ethereal environment, created with the help of hurricane lanterns, lamps, and matchsticks used for lighting cigarettes.

According to his stage directions, as the play begins, a lantern on the ground dimly lights the graveyard from a low angle – a portfolio bag, open at the top, a glass tumbler, and a spread-out handkerchief lie beside it. The Leader, who was sitting on the handkerchief a moment ago, enters shouting at the guard. (The eerie atmosphere is perhaps too disturbing for him to bear it alone, and hence his scream for company.) The guard responds to his call by running in, panting, and a little frightened. He holds another lantern but the light has gone out. As the play progresses, Munier Chowdhury opens enough scope for the use of unconventional lighting and costuming devises. For example, Inspector Hafiz is instructed to enter without a lantern, and thus the initial impression is a bit of a shock for the Leader. The scene between the two is lit by the lantern on the ground, seen in the beginning, and the occasional light from lit matchsticks. Murda Fakir also enters in the dark but when the dead arise, each holds a lamp, and hence the source lights their face from a low angle. When Inspector Hafiz impersonates as the Mother and then the Wife, he rearranges his shawl so as to cover his head with it, and thus give the impression of wearing a sari. Towards the end, when the guard runs in again to inform the Leader and Inspector that the dead have been buried, he is lit by a lantern that he carries—this time it is seen burning.

Munier Chowdhury passed the play-text on to Ranesh Dasgupta. The inmates of cell No. 2 decided that Fani Chakrabarty would direct it with the following cast: Nalini Das as Murda Fakir, Dhananjay Dash as Police Inspector (and also the Mother and the Wife), and Ajay Ray as the Political Leader. Amal Sen designed the set and executed it at one end of the cell. On the downstage end, he placed mattresses provided at the jail, with chunks of grass-laden earth on top. The Leader, Police Inspector, and Guard played in this area. A 'half curtain' of black cloth, rising about three to four feet from the ground, masked the upstage half of the performance space. The dead rose from behind this curtain. The entire undertaking was carried out surreptitiously, without any assistance from jail authority.

On 21 February 1953, a little after 10 in the late evening, the inmates of the cell No. 2 performed the play – by the light of lanterns, lamps, and matchsticks. The performers played for a group of spectators in the intimate space of the cell, held together by their common identity as political activists and members of the Communist Party. Except the director, Fani Chakrabarty, who was a renowned actor from Barisal, other performers had very little experience of performing in theatre. Nevertheless, their political commitment, and their aim of building solidarity amongst the inmates and raising their spirit worked to infuse the magic of a charged performance that was an act of defiance against the state. Although Munier Chowdhury could not see it because he was being held at a different cell, he was informed that the performance was extremely successful. Dhananjaya Dash writes, 'I still can hear Nalini-da's heart-rending crying. […] Nalini-da's dialogue and expression for the dead who were lying in that graveyard gave shape to the wonderful talent of a born actor'. However, Ranesh Dasgupta expressed his displeasure at the ending of the play. According to him, Munier Chowdhury had diffused a potent sign of subversion into a hallucination under intoxication, under eerie circumstances of the graveyard. In his view, had the playwright a clear political conviction or, had he not suffered from doubts and contradictions, then the play would have ended differently.

Munier Chowdhury's second term of imprisonment, during which time he wrote Kabar, ended in 1954. However, he was imprisoned again after two months in the same year. He passed his MA (Final) in Bengali while in jail, and stood first in the first class. After his release in the same year (1954), he re-joined the university and transferred himself to the Department of Bengali in 1955. In 1958, he obtained Masters in Linguistics from Harvard University. Although he continued to be a sympathizer of the progressive movement, voicing protest against repressive measures of the government of Pakistan, never again did Munier Chowdhury get directly involved in politics, or write another Kabar. Later, when questioned in an interview, why he disassociated himself from active politics, he answered, 'I have been disillusioned with life.' The Government of Pakistan awarded him Sitara-i-Imtiaz for his silence, but he disowned the award in early 1971. However, the government of Pakistan did not forget his tacit and silent support for the Bengali nationalist movement. On 14 December 1971, he was picked up from his home by anti-Liberation forces (Al-Badr and Al-Shams), to be executed by Pakistan Army. His body was never found.

Munier Chowdhury, you live forever in our heart.

Syed Jamil Ahmed is a Theatre director, and Honorary Professor of Department of Theatre and Performance Studies at University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments