Munshi Meherullah of Jessore and religious identity in 19th century Bengal

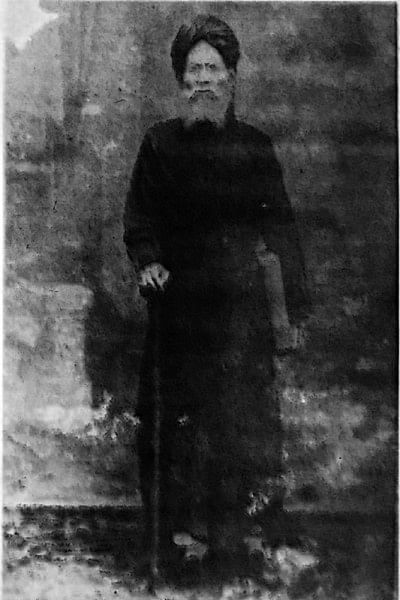

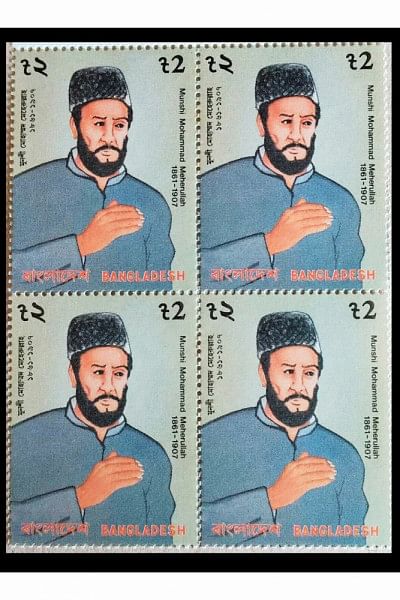

On 7 June 1907, a rural Bengali tailor, Meherullah, died of complications from pneumonia in a small village called Chatiantala, on the banks of the river Bhairab, in Jessore. Jessore was, as the imperial gazetteer L. S. S. O'Malley put it, a 'land of moribund rivers and obstructed drainage, notoriously unhealthy, with fever silently and relentlessly at work, destroying many, and sapping the vitality of the survivors and reducing their fecundity.' In the wet, humid, and marshy environs of riverine eastern Bengal, such deaths were not uncommon. What can the life of a tailor illuminate for us about the spaces and politics of religion and language, or legitimacy of belonging and identity, in Bengal of the late nineteenth century? In the small, unremarkable tragedies of rural peasant life, Meherullah's story could have been an ordinary chapter and Meherullah's memory lost to the archives of history. However, his extraordinary qualities of oratory and his unlikely influence on Bengali-Muslim society of the late nineteenth century make this story more complicated.

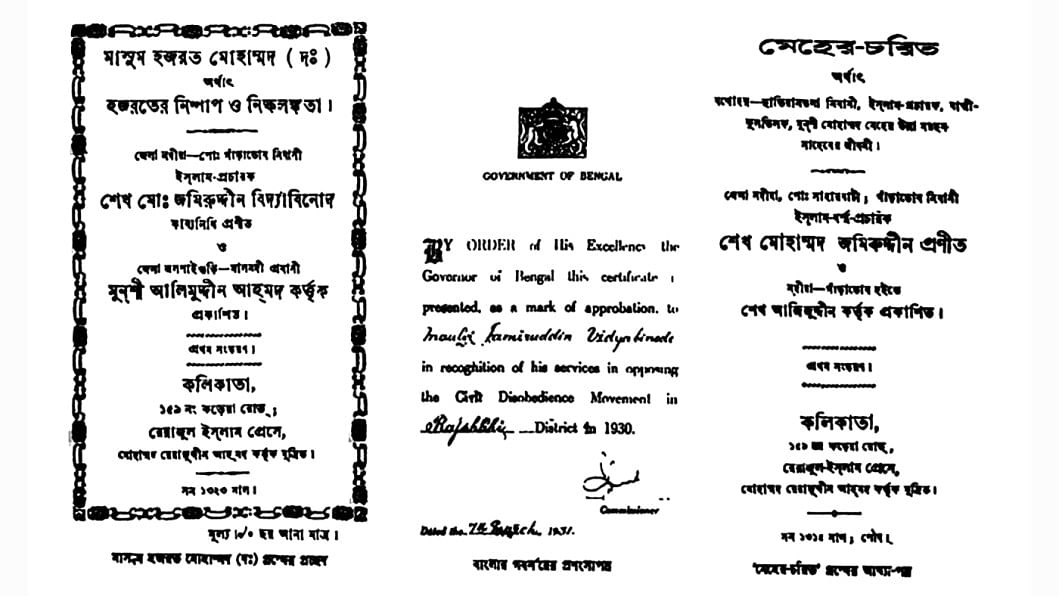

Meherullah's murid Jamiruddin wrote a short biographical essay of his master after Meherullah's death, published in the periodical the Islam Pracharak. Called Meher Charit, this biography is the most authentic contemporary record of Meherullah's life and labors and acted as the source material for two subsequent biographies of Meherullah, written by Asiruddin Pradhan of Jalpaiguri and Habibur Rahman. Since these quasi-hagiographic literary works are our main source of knowledge about Meherullah, they interestingly provide the historian with a portrait of the common man reimagined as hero. We can see how Meherullah became more than what he was, not only a charismatic self-taught tailor who assumed the role of spokesman for Bengali Muslims in his battle against Christian evangelism and conversion, but also an ideologically inscripted cipher holding the key to the Bengali Muslim mofussil milieu and mentality.

The ripples of dismay at Meherullah's death spread from Jessore to Dhaka and then to Calcutta. The premier Bengali-Muslim weekly periodical, Mihir-o-Sudhakar, published by Sheikh Abdur Rahim, led the chorus of grief-stricken obituaries. The periodical printed a notice that lamented the fate of the subaltern Bengali-Muslim society of Bengal, particularly eastern Bengal: "The political and religious world of Bengali Muslims is shrouded in great darkness. The person who dedicated his life to the uplift and reform of religion and society and infused a new life in Bengali Muslims, that preacher of the true values of Islam, Munshi Mohammad Meherullah, alas, is no more. The Christian padris shook in fear when they heard him defend Islam. His advice brought many Christian converts back into the fold." Other important Bengali-Muslim periodicals and newspapers echoed the Mihir-o-Sudhakar, including the Soltan, the Islam Pracharak, as well as the Moslem Suhrid, which emphasized the profound social loss Meherullah's passing had caused. It is very clear from the tone of these obituaries that Munshi Meherullah had transcended his very humble origins to occupy the role of reformer and social conscience for a large section of Bengali Muslims, across the spectrum of class and sectarian differences, from the plebeian atrap to the aristocratic ashraf.

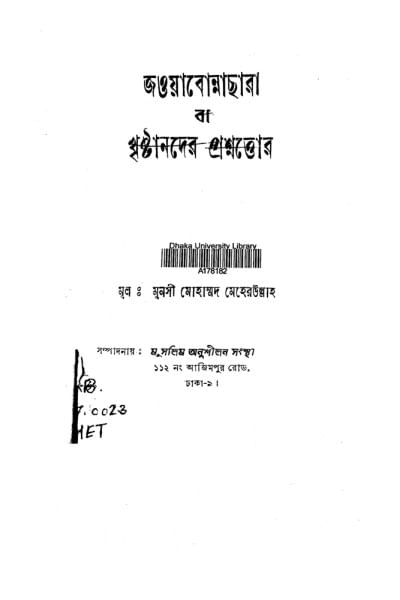

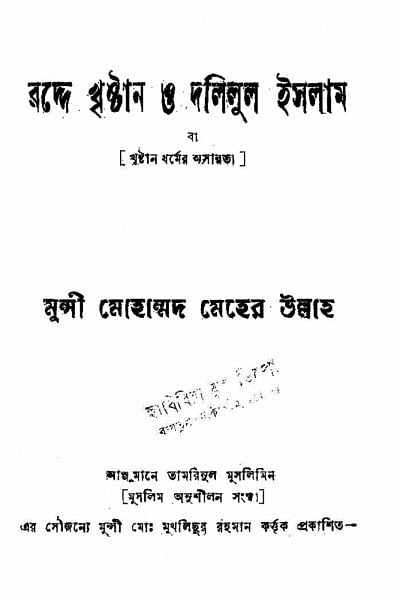

As we have seen, Meherullah's acceptability as a spokesman for the religious, political, and social aspirations of Bengali Muslims was acknowledged by the centers of high intellectual exchange in Calcutta and Dhaka through the print medium. The Bengali Muslim public sphere, aided by the print media, helped disseminate Meherullah's opinions, especially to the educated ashraf or elite Muslims. This was done by allowing him the space to write and contest Christian evangelical polemics in the pages of fairly widely subscribed periodicals and pamphlets, most of which were straightforward transcriptions of his speeches. Meherullah's characteristic apologetics against Christian evangelism translated into the print medium with vibrancy and humor. For example, his Jawabunnesara or Answers to major theological questions used by the missionaries in an effort to critique Islam, written in 1898, took the form of a dialogue between a Christian missionary and himself.

One of the questions directed attention towards the fact that there were no easily available Bengali translations of the Quran. As such, wasn't it fruitless to read the words of Allah by rote in a language that the namazi could not hope to comprehend? This was a deeply Protestant Christian concern about the comprehensibility of the Holy Word, but also served as a direct attack on the nature of Muslim piety in Bengal. Meherullah in his answer used the rhetoric of practical common sense. In riverine eastern Bengal, many hundreds of men and women bought tickets printed in English for boats and steamers, not knowing the language or what it meant for their journey, and still had faith that they would reach their destinations. Was it not evident that Allah and the alims would steer the devout Muslims on the path of piety even if they couldn't read the Quran in Arabic? His oratorical powers were exceptional – the power of the spoken word, and his ability to yield it precisely for the intended audience, helped him to appeal to the large sections of illiterate or literacy-aware peasant Muslim communities, spread in the remote rural areas of deltaic Bengal, who would gather by the thousands to hear him give speeches at the waz-mahfils or engage Christian missionaries in debate in deeply antagonistic but entertaining bahas'es.

Abul Ahsan Chaudhuri pointed out that the decades-long vicious cycle of epidemics, flooding, famines, and the unsettled agricultural ecosystem in the aftermath of Indigo-troubles, led to population decline and breakdown of socio-economic infrastructure in Nadia and Jessore. The lack of education, a tattered rural economy, and repeated natural calamities combined with charitable efforts of Christian missions and devout colonial administrators, meant that this region became one of the only places in Bengal other than the 24 Parganas to evince success in non-elite Christian conversions. Poverty and illiteracy made the Muslim peasantry particularly vulnerable to conversion efforts. Meherullah's relentless apologetics against evangelism stemmed from the recognition that in many cases, Muslim conversions to Christianity were the result of the wretched conditions of existence in rural Bengal. The general lack of medical care, access to education or employment, and the often-unprofitable business of agriculture that was at the mercy of moneylenders and erratic weather, exacerbated the situation. Missions provided education, employment and medical care, fundamentally important services.

Meherullah was deeply conscious of the material conditions of performance of faith and was also aware that this could be exploited in his preferred form of social activism and religious reform. He wrote, 'Enchanted by the imaginary idea that Christianity was the true religion, recently many thoughtless Musalmans have gone ahead and had their names recorded in the registers of Christian Missions, and thus have now a share of free bread.' His opinion was a common one, as evidenced by a folksong from Nadia:

নদীয়া জেলার আজি বেরাদর'গন।

যত কেরেস্তান লোগ কর দরশন।

বাপদাদা তাহাদের আকালের বারে।

পেটের দায়েতে মজে যীশু মন্তরে।

Look, brothers from Nadia,

Look at all these Christian people!

Their forefathers, during the famine,

Compelled by hunger sang Jesus's praise!

For Meherullah and the Bengali-Muslim intelligentsia at large, it was this understanding of the materiality of religious faith and religious identity that determined their stance on Bengali Muslims, especially of the non-elite Muslim peasantry of eastern Bengal.

James Wise, in a seminal essay published in 1883, made a series of observations about the relationship between Muslims and native Christian converts. Like high-caste Hindus, Muslims of Bengal practiced untouchability towards Christians. On coming into close contact with the person, clothing, or food of the native converts, they would bathe. And if a convert entered their home, they would throw away all cooked food and drinking water. They did not practice similar rituals of taboo with low-caste Hindu neighbors. Educated middle-class Muslims would not sit at the same table with Christians, even with British officials. Wise's observations are borne out by the descriptions Kazi Nazrul Islam left of the so-called 'low-caste' Muslims and the 'Oman-Kathlee' (Roman Catholic) inhabitants of Ranaghat and Krishnanagar in his novel Mrityu Khuda published in 1930.

In such a society, the visibility of Christian missions, the implicit racial hierarchies practiced by the missionaries and colonial officials and the explicitly insulting nature of Christian apologetics, especially about the Prophet, created an impression in the Bengali-Muslim ecumene of a much larger threat of Christianity. The Islam Pracharak of September 1891 complained: "The primary enemies of our religion are the Christians. They spend hundreds of thousands of rupees each year. When there are famines, they lure the wretched sufferers of those regions with promises of aid." The Anjuman'e Ettefaq'e Islam concurred – "Many of [the peasants] sought sanctuary with the missionaries during the last terrible famine. If the Muslims had money or education that enlightened them to the true glories of Islam, they'd never ever convert to Christianity."

Meherullah affected clear disinterest in open debate with his missionary interlocutors in bahas meetings, deferring their theological enquiries with a joke, a folktale, a recitation from a Persian poem, using laughter and an almost parable-like use of everyday practices. There are two reasons for such performances. One, the very act of engagement with the racially inflected theological debates between Christian missionaries and Muslim alims was, Meherullah understood, merely a performance of social, racial, and theological superiority. The outcome of such debates was always undecided and indefinitely deferred because apparent victory for any one side was completely unacceptable, at the peril of their very souls and identities, to the other side. Meherullah cut through the dense minutiae of arid scriptural thicket and made the contest merely about demonstrations of superior wit before a deeply partisan audience, usually predisposed towards him. This strategy was also an effective way to disconcert the missionaries, who traditionally based their salvos against Islam, only after a thorough study of both the Quran and the tafsir literature. Deprived of this common ground, they floundered at Meherullah's sly challenges to their textual authority.

Meherullah's actions remain opaque to the historian if studied within the rigid categories of reform, modernity, and colonialism. The distinctive approach of Meherullah towards social reform, religion and religious identity played a very important role in defining self and other in Bengal, with important consequences. Defining the parameters of being a good Muslim demarked the boundaries of identity, where religion and social capital were interwoven, proximate and omnipresent strands. The threat of Christian conversion enabled self-examination and analysis of one's immediate social milieu in Bengali Muslims, in order to resist the material lucrativeness of religious and political subordination, and to bring about reform from within.

Meherullah, in his capacity to travel across networks of information-exchange, from the elite ashraf circles of the Mihir-o-Sudhakar in Calcutta to the bahas and waz-mahfils of the villages and mofussil towns of rural Bengal, complicates our notions of who could speak for the community and the nation. In fact, Meherullah's imagined community, imagined against Christianity and colonialism, opens up an interesting arena of processual understanding for rights and identities. He was an interlocutor of his social milieu, mediating between the present and the past in a voice that could not be drowned out by the larger intellectual currents of nationalist historiography that has privileged the Hindu/Brahmo point of view. Meherullah possessed what Ranajit Guha called "the small voice[s] of history", recovered from the ruins of the vernacular pasts.

Mou Banerjee is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments