Partition 1947: PARTITION or UNITY? BENGAL in 1947

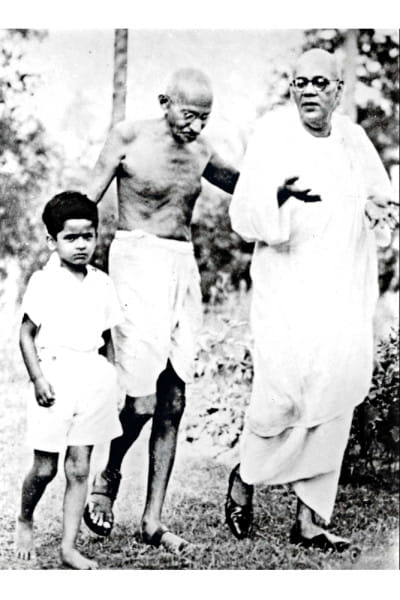

Between May 9 and 14, 1947, in Sodepur near Calcutta, Mahatma Gandhi had a fascinating set of conversations with Hindu and Muslim leaders of Bengal. Sarat Chandra Bose (seen in photograph with Gandhi) explained to him the ethics underlying the effort to preserve the unity of Bengal based on an equitable sharing of power between the two major religious communities. Gandhi told Abul Hashim on May 10 that he was trying to become a Bengali and that he was learning Bengali to be able to appreciate the poems of Rabindranath Tagore in the original. Hashim mentioned that Bengali Hindus and Muslims alike revere the poet. Gandhi argued that the spirit of the Upanishads connected Rabindranath to the entire corpus of Indian culture. If Bengal voluntarily wanted to be associated with the rest of India, Gandhi enquired, what might Hashim have to say about that proposition? On May 12 the Mahatma gave Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy a written undertaking that he was even prepared to act as "his honorary private secretary" so long as the Muslim leader worked with sincerity for both Hindus and Mussalmans to preserve the unity of Bengal.

On hearing that Sarat Bose's united Bengal plan had received Gandhi's support, the Hindu Mahasabha leader Syamaprasad Mukherjee rushed to Sodepur. The Mahasabha had been clamoring for the vivisection of Bengal ever since the British prime minister Clement Attlee made his February 20, 1947, announcement of their intention to quit India by June 30, 1948. The Mahatma wanted Syamaprasad to see the merits of the proposal to keep Bengal united. "An admission that Bengali Hindus and Bengali Mussalmans were one," Gandhi explained, "would really be a severe blow against the two-nation theory of the League."

The Muslim League took its stand in favor of safeguards for minority rights until 1940 when Mohammad Ali Jinnah claimed that the Muslims of India constituted a nation. As he put it, the term nationalist had become a 'conjurer's trick' in politics. With some prodding from the British viceroy Linlithgow, the Muslim League resolved at its Lahore session in March 1940 that the Muslim-majority provinces in the north-west and east of British India should be grouped to constitute independent states. In addition to speaking about these Muslim states in the plural, the resolution moved by Fazlul Huq also spoke of a constitution in the singular that would govern minority rights throughout the subcontinent. It mentioned neither the word 'partition' nor the name 'Pakistan'.

The claim to Muslim nationhood, as Ayesha Jalal has shown, was not an inevitable overture to separate and sovereign statehood. The interests of Muslims in provinces where they were in a minority were not the same as those of Muslims in the majority provinces of the north-west and the east, which sought a high degree of autonomy. The Muslim League faced an insurmountable challenge in trying to resolve these contradictions. When Rajagopalachari offered a Muslim state based on the partition of Punjab and Bengal in 1944, Jinnah dismissed it as 'a shadow and a husk', 'a maimed and mutilated' version of their demand.

During World War II Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was able to forge a remarkable unity among Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians in his Azad Hind movement. A political disciple of the fair-minded Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das, who had forged the Bengal Pact between Hindus and Muslims in 1923-1924, he was committed to unity based on equality. That spirit of solidarity was widespread within India during the Red Fort Trial of the three Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh officers of the Indian National Army during the winter of 1945-1946. The British finally recognized that they would have to quit India. The Cabinet Mission arrived in the spring of 1946 to hold talks. It seemed possible that the unity of India could be preserved within a federal arrangement of three groups of provinces proposed by it. Once the Congress under Jawaharlal Nehru declared that grouping might not last, the Muslim League under Jinnah called for direct action to achieve Pakistan.

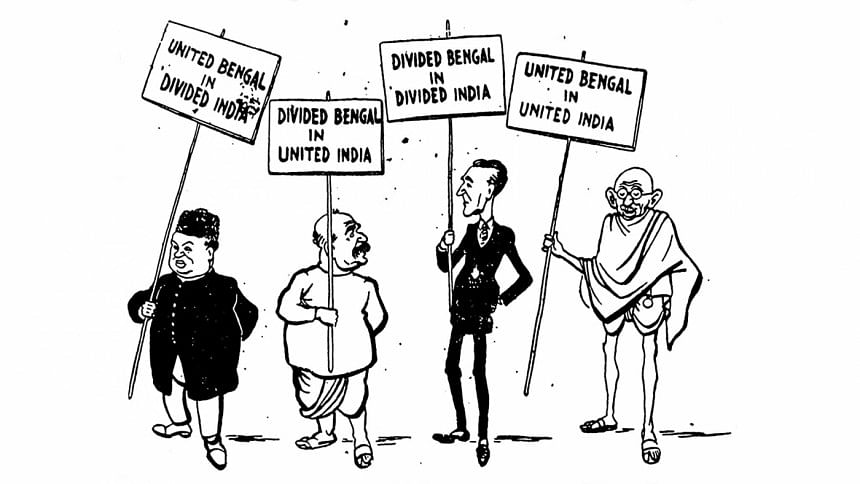

On March 8, 1947, the Congress under Nehru echoed the Hindu Mahasabha demand for the partition of Punjab and added that the principle of partition may have to be applied to Bengal as well. Conceding Pakistan based on the partition of these two crucial Muslim-majority provinces would enable the Congress High Command to inherit the unitary center of the British raj. In an editorial on April 11, 1947, the Bengali paper Millat charged the Congress and the Mahasabha of performing Parashuram's role of raising a parashu (axe) to slice "Mother" into two. It asked why the Congress after preaching the high ideal of unity was now dancing on the same platform with the Hindu Mahasabha.

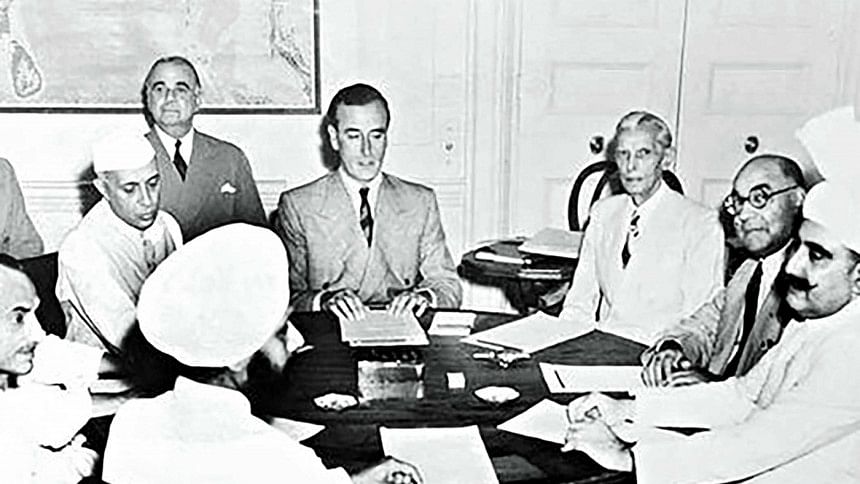

The united Bengal plan was a final and failed attempt to preserve religious harmony and the unity of Bengal by the more far-sighted Hindu and Muslim leaders. It received the backing of Jinnah and Gandhi in April and May 1947. After amending the plan by taking note of Gandhi's suggestions, Sarat Bose sent a final version through George Catlin to Mountbatten. Catlin was a well-known British Member of Parliament and political theorist, husband of the writer Vera Brittain and father of the future Labor and Liberal Democrat politician Shirley Williams. He had been staying at Sarat Bose's Woodburn Park home as a guest in May 1947. In London on May 28, 1947, Mountbatten recorded two alternative broadcasts. According to Broadcast B, the Hindu and Muslim leaders had come to a power-sharing agreement to form a new coalition government, leaving Punjab alone a candidate for partition. On Mountbatten's return to New Delhi on May 30, Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel vetoed the exception for Bengal. As a result, Mountbatten announced the partition plan on June 3, 1947, that had been the substance of his Broadcast A.

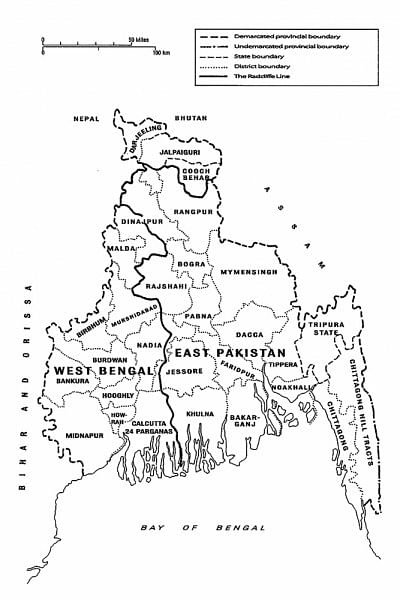

The British had decreed partition while making a hollow statement about ascertaining the will of the people through votes by members of the legislative assemblies of Bengal and Punjab. On June 20, 1947, East Bengal legislators voted by 106 votes to 35 against partition while the legislators of West Bengal voted by 58 votes to 21 in favor of partition. Since the Mountbatten plan had provided for partition if any one side wanted it, the vivisection was ratified. The economic problems between mostly Hindu landlords, traders, and moneylenders and a predominantly Muslim smallholding peasantry of East Bengal – a theme discussed in my book Agrarian Bengal – required a very different solution from the territorial division that took place in 1947.

The two dominions Pakistan and India did not know precisely where their borders lay when they came into being on August 14-15, 1947. The Radcliffe decision on the partition lines was not announced until August 17. Nearly two million people were killed in horrific violence while at least fourteen million refugees fearfully crossed the newly demarcated borders. Having abdicated all responsibility for maintaining order, Mountbatten congratulated himself on having carried out one of the greatest administrative operations in history. The incompetent surgeon named Radcliffe had also left enclaves. I worked as a parliamentarian on the exchange of enclaves between India and Bangladesh that was finally accomplished by the ratification of the Land Boundary Agreement in 2015.

In Punjab there was an almost wholesale forced exchange of population in 1947. In Bengal the migratory flows continued in fits and starts between 1947 and 1971, leaving significant religious minorities in both Bengals. The specter of a great religious divide in 1947 masked center-region tensions and contributed to centralization of state power in both post-colonial India and Pakistan, stifling the voices calling for a healthier dose of federalism.

Mahatma Gandhi and a handful of principled leaders of the freedom struggle tried unsuccessfully to avert the human tragedy of partition. Only one leader working alongside Gandhi could have worked out an equitable layering and sharing of sovereignty instead of the batwara of territory at an unacceptably high human cost. That was Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose who commanded the trust of all the religious communities and linguistic groups of the subcontinent. Gandhi spent August 15, 1947, quietly in Calcutta, away from the festivities surrounding independence in Delhi. On January 23, 1948, he pointed out that Subhas "knew no provincialism nor communal differences"; he "had in his brave army men and women drawn from all over India without distinction and evoked affection and loyalty, which very few have been able to evoke." "In memory of that great patriot," Gandhi called upon everyone, to "cleanse their hearts of all communal bitterness." "Let us permit ourselves to hope," he said on January 26, 1948, "that though geographically and politically India is divided into two, at heart we shall ever be friends and brothers helping and respecting one another and be one for the outside world."

"I do not wish to disturb the partition of Bengal which has already taken place," Sarat Chandra Bose wrote in an "Appeal to India and Pakistan", an hour before his death on February 20, 1950. Instead, he wanted to "let East Bengal live and flourish as a distinct and separate State". Fazlul Huq visited Netaji Bhawan in Calcutta as the premier of East Bengal in 1954 at the head of the United Front government. He spoke emotionally about the Bose brothers and questioned the division along lines of religion. His government was dismissed soon after his return to Dhaka and East Bengal placed under the rule of a military governor. An ordeal of suffering and sacrifice was the price that was paid by Bangladesh to win freedom in 1971.

The decisions of expediency in 1947 continue to haunt the quest for equal citizenship in South Asia. Seventy-five years after freedom the people of the subcontinent owe it to themselves to finally heal the wounds of partition.

Sugata Bose is the Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs, Harvard University

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments