Rabindranath Tagore and the creation of national identity

Rabindranath Tagore is perhaps the only poet whose songs were chosen as the national anthems of two countries: India and Bangladesh. On January 24, 1950, Tagore's song "Jana Gana Mana" was officially adopted by the Constituent Assembly as the Indian national anthem. Twenty-two years later, on January 13, 1972, an earlier song of Tagore's, "Amar Sonar Bangla," was officially recognized as the national anthem of Bangladesh. If a country's national anthem epitomizes the identity of the country, how do these two songs epitomize the identities of India and Bangladesh? Furthermore, is there something ironic in choosing these two songs that had been composed in different circumstances – one mourning the partition of Bengal and the other celebrating the annulment of that partition – as the national anthems of two countries? Does giving a song an "official" status deprive it of its richness and even complexity? Especially, as in both cases, only a few lines of the songs are the national anthems? In the case of "Amar Sonar Bangla," in particular, has its institutionalization weakened its evocative power as the rallying cry for Bengalis in 1971?

On July 20, 1905, the British Raj announced the partition of Bengal. The partition would take effect from October 16 that year. The new province of Eastern Bengal and Assam would include the districts of Dacca, Mymensingh, Faridpur, Backergunge [Barisal], Tippera, Noakhali, Chittagong, the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Rajshahi, Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Rangpur, Bogra, Pabna, and Malda. While the official reason behind the partition was that the Bengal province was too large to be administered by a single governor, the division of the province into a Hindu-dominated one and a Muslim-dominated one could be considered but another example of the British "Divide and Rule" policy.

There was almost immediate reaction to the announcement of the partition. The anti-British Swadeshi movement was launched on August 7, 1905, at a public meeting at the Calcutta Town Hall, when the Boycott Resolution was passed. By September 1905, the sale of British cloth in some districts fell to between 6 and 20 per cent of original levels. Public burning of foreign cloth took place spontaneously. Earlier attempts to boycott foreign cloth had failed to elicit this response. If Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, meant to curb the rising tide of nationalism, he succeeded in doing just the opposite. The anti-British feeling led to a new wave of patriotism as well as increasing violence.

Rabindranath Tagore too became involved in the swadeshi movement. Though he did not approve of violent methods – as his novel Ghare Baire reveals – his initial reaction to the partition was an outpouring of grief over the dismemberment of his motherland. Among the songs he composed at this time were "Banglar Mati Banglar Jal," "Bidhir Badhon Katbe Tumi Emni Shaktiman," "Jodi Tor Dak Shune Keyu Na Ashe Tobe Ekla Chalo Re," and "Amar Sonar Bangla."

In the face of these protests, the partition was annulled in 1911. At The Great Coronation Durbar on December 12, 1911, King George V announced the annulment of the partition. But there was a price: From Calcutta, the capital was shifted to Delhi.

On the occasion of the visit of King George V to the Delhi Durbar, Rabindranath Tagore was asked by a friend to compose a song. While he did not write a song for the Durbar, he did write one for the annual meeting of the Congress. The wordings of the song suggest that it was written in praise of George V. The Statesman, for example, on December 28, 1911 stated, "The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore sang a song composed by him specially to welcome the Emperor." The Englishman also noted "The proceedings [of the Congress] began with the singing by Rabindranath Tagore of a song specially composed by him in honour of the Emperor." Reba Som notes, in Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and His Song, that though Tagore did not write a song for George V, "Jana Gana Mana" "was deliberately ambiguous" (103). In 1911, the dispenser of India's destiny was, in all practicality, the British ruler.

Tagore would insist that the poem was not in praise of King George and the word "Chirasarathi," which he translated as "Eternal Charioteer" in his translation of 1919, referred to Krishna. However, it is not improbable that in 1911 with the annulment of the partition of Bengal, Tagore was celebrating the reunification of India – but it was a reunification that had been made possible by the then ruler of India's destiny. Tagore's anti-British feelings would not come to a head until 1919, after the Jalianwallah Bagh atrocities when he renounced his knighthood awarded by George V in 1915.

In January 1912, the Brahmo Samaj journal, Tatva Bodha Prakasika, published the song. Below is a transliteration of the first stanza.

Jana gana mana adhināyaka jaya he

Bhārata bhāgya vidhātā

Pañjāba Sindhu Gujarāṭa Marāṭhā

Drāviḍa Utkala Vaṅga

Vindhya Himāchala Yamunā Gaṅgā

Ucchala jaladhi taraṅga

Tav śubha nāme jāge

Tav śubha āśiṣa māge

Gāhe taba jaya gāthā

Jana gaṇa maṅgala dāyaka jaya he

Bhārata bhāgya vidhāta

Jaya he, jaya he, jaya he

Jaya jaya jaya, jaya he!

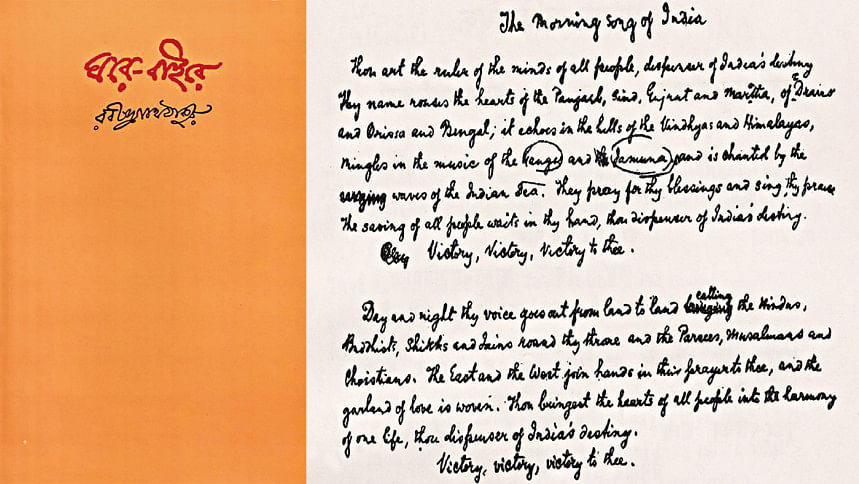

In February 1919, Tagore accepted an invitation from the Irish poet James H. Cousins, Principal of the Besant Theosophical College, to spend a few days with him and his wife, Margaret. After listening to Tagore singing the song, Margaret set down the notation which is still followed. It was here that Tagore wrote his English translation of the song, titling it The Morning Song of India. The first stanza describes the varied land of India and its people.

Thou art the ruler of the minds of all people, dispenser of India's destiny.

Thy name rouses the hearts of Punjab, Sind, Gujrat and Maratha, of the Dravida and Orissa and Bengal; it echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and Himalayas,

mingles in the music of Ganges and Jamuna and is chanted by the

waves of the Indian Sea. They pray for thy blessings and sing thy praise.

The saving of all people waits in thy hand, thou dispenser of India's

destiny.

Victory, victory, victory to thee.

In 1941, shortly before his death, Tagore wrote the essay "Crisis in Civilization." Despondent over the violence that attended the anti-British movement, Tagore looked forward to a time when the British would indeed leave India and man's humanity would prevail.

The wheels of Fate will some day compel the English to give up their Indian empire. But what kind of India will they leave behind, what stark misery? When the stream of their centuries' administration runs dry at last, what a waste of mud and filth they will leave behind them! I had at one time believed that the springs of civilization would issue out of the heart of Europe. But today when I am about to quit the world that faith has gone bankrupt altogether.

As I look around I see the crumbling ruins of a proud civilization strewn like a vast heap of futility. And yet I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man. I would rather look forward to the opening of a new chapter in this history after the cataclysm is over and the atmosphere rendered clean with the spirit of service and sacrifice. Perhaps that dawn will come from this horizon, from the East where the sun rises. A day will come when unvanquished Man will retrace his path of conquest. Despite all barriers, to win back his lost human heritage.

While Tagore describes the beauty of Bengal in the poem, it is only the entire poem that reveals that it is also about the political situation at the time. The last two lines refer to the boycott of foreign goods and in an almost prophetic vision foresee the hanging that would be the result – as it indeed was when Khudiram was hanged.

Unfortunately, when the British left India, there was a cataclysm more violent than any Tagore had visualized. The Indian subcontinent was divided into two nation states, with India in the middle of the two wings of Pakistan: East and West Pakistan. The early patriotic fervour in East Pakistan soon faded as people started feeling that they were being treated as second-class citizens. One of the issues was that of the state language. This issue came to a head in 1952 when Governor-General Khawja Nazimuddin defended the "Urdu-only" policy in a speech on January 27. Police action on February 21 led to the killing of at least six persons. The language movement and the killing of protestors was the catalyst for an awakening nationalist consciousness among the Bengalis of East Pakistan. Though the central government granted official status to Bangla in 1956, the awareness that the people of East Pakistan were Bengalis first and Muslims later led to increasing distancing from West Pakistan.

The awakened Bengali consciousness was given a boost on the cultural side when, in 1961, the government of Pakistan attempted to ban the singing of Tagore songs in East Pakistan. However, a group of intellectuals and singers defied this ban and celebrated Tagore's birthday. Subsequently, a cultural organization was formed to nurture and foster the cultural aspect of the land, including the celebration of the birthday of Tagore. Chhayanat initiated the celebration of the Bengali New Year on the first day of Baisakh, April 14, 1963 with Tagore's song "Esho Esho He Baisakh." The song not only celebrated the coming of a new year, but also stressed the cultural unity of the people of Bengal. Thus, if Tagore recognized the multi-ethnic, multi-religious Indian identity in "Jana Mana Gana," his songs helped to create a sense of Bengali identity distinct from the Pakistani Muslim one. Subsequently, as the movement for autonomy grew and increasingly in 1971 after the crackdown, Tagore's "Amar Sonar Bangla" became popular as the song which epitomized the meaning of the land for the dispossessed Bengali.

While Tagore describes the beauty of Bengal in the poem, it is only the entire poem that reveals that it is also about the political situation at the time. The last two lines refer to the boycott of foreign goods and in an almost prophetic vision foresee the hanging that would be the result – as it indeed was when Khudiram was hanged. With "Amar Sonar Bangla" elevated to the status of the national anthem, we are deprived of the complex feelings that inspired the poet to write these lines. The poem is not just about beauty but also about separation, about the cauldron of history in which much creation occurs.

The circumstances under which "Amar Sonar Bangla" was created are interesting and reveals Tagore's openness to borrowing whatever he found good. Between 1891 and 1901, Tagore resided at the family estate of Shilaidaha, on the south bank of the Padma in Kushtia. Apart from composing poems and songs, Tagore was fascinated by the songs of the wandering baul singers. The universal message of their songs appealed to him as did their evocative tunes.

In 1905, when Tagore was writing his songs of protest, he used the tune of Gagan Harkara's "Ami Kothay Pabo Tare" to accompany the lyrics of "Amar Sonar Bangla." The song which first appeared in the September 1905 issue of Bangadarshan describes the beautiful land of Bengal and perhaps owes something to the baromashi, the Bengali song of separation which refers to the different Bengali months and their seasonal changes. However, the English translations of Tagore's song – perhaps to make it more understandable to readers unfamiliar with the Bengali months – use "Spring" and "Autumn" instead of "Phalgun" and "Agrahayan."

The official English version of the first stanza is that by Syed Ali Ahsan, himself a Bangla poet.

My Golden Bengal

My Bengal of gold, I love you

Forever your skies, your air set my heart in tune as if it were a flute.

In spring, my mother mine the fragrance from your mango-groves makes me wild

with joy –

Ah, what a thrill!

In Autumn, Oh mother mine,

In the full blossomed paddy fields,

I have seen spread all over – sweet smiles!

Ah, what a beauty, what shades, what an affection

And what a tenderness!

What a quilt have you spread at the feet of banyan trees and along the bank of

rivers!

Of mother mine, words from your lips are like nectar to my ears!

Ah, what a thrill!

If sadness, Oh mother mine, casts a gloom on your face,

My eyes are filled with tears.

In 1972, the song that Tagore had composed in protest against the division of Bengal became the national anthem of a sovereign country, the seeds of which had perhaps been sown in 1905 with that division. While celebrating Bengal, the song, by becoming the national anthem of Bangladesh, reifies the division that had created the province of Eastern Bengal and Assam and which, after much blood shed, became Bangladesh – but a Bangladesh reduced in size because Assam had not been part of East Pakistan and was not subsequently part of Bangladesh.

Niaz Zaman is a retired academic, writer and translator.

"Rabindranath Tagore and the Creation of National Identity" was first presented at the conference on "Redefining Paradigms of Sustainable Development in South Asia," organized by Sustainable Development Policy Institute, Islamabad, Pakistan, in December 2011. This is a shorter version of the developed essay published in Chaos, IUB Studies in Literature, Language and Creative Writing, Fall 2012.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments