Rammohun Roy’s Grammar(s) of Bangla

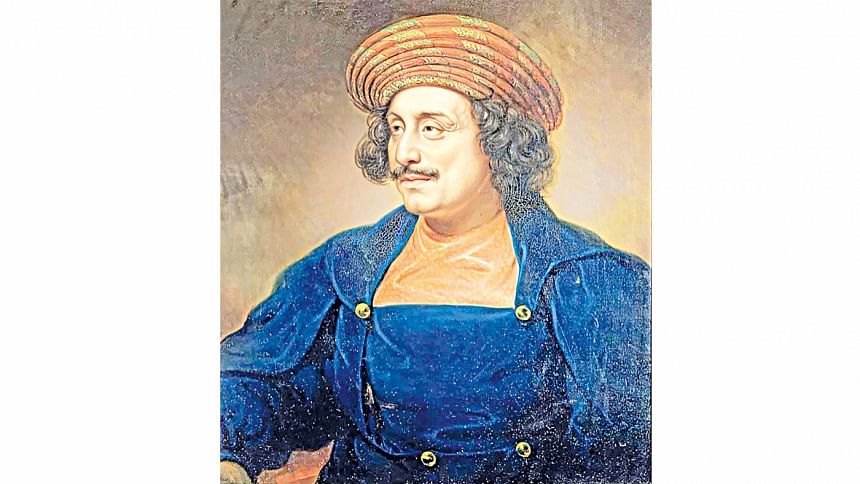

Although Rammohun Roy was notably many things, he was not an unlikely person to write a grammar—or, in fact, two grammars: one in English and one in Bangla, the latter being a free translation of the former. He was a polyglot, and once you know more than one language, you are naturally curious about the structures of them—how different or how alike they are. And next a deeper question begins to haunt you: Why are they alike or different? If, however, the languages in question are genetically related, their structures and vocabulary may have something in common. But if they come from different and unrelated families, the areas of surface divergences may be wide. Rammohun (1772-1833) knew languages that were quite different from one another, Bengali, English, Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, etc.

It is, however, quite a happy fact that he did not write a comparative grammar of the languages he had known, but, avoiding the temptation, he decided to write a grammar of his own language, Bangla. Of course, one knows that there are hundreds of kinds of Bangla—its dialects, class varieties, or sociolects, Bangla of different times, etc. But Rammohun wrote a grammar of what was the written norm of the day, the standard written dialect of Bangla, otherwise called the Sadhu Bhasha, without ignoring the spoken colloquial standard form. He also was the first Bengali to write an original grammar of the language. The earlier grammar of Mitrityunjay Vidhyalankar was not an original work, but arguably a translation of William Carey's grammar.

2

As we have hinted before, Bengalis were not the first to write grammars of Bangla. It was a Portuguese churchman, Fr. Manoel da Assumpcam, who first prepared a sketch of Bangla grammar in his Vocabulario em idioma Bengalla e Portugueze divide em duas partes (1742?), that is, 'Vocabulary and Idioms of Bangla and Portuguese divided in two parts.' The second Bangla grammar, this time a fuller treatment, was also written by a foreigner, the Englishman Nathaniel Brassey Halhed (1751-1830), whose Grammar of the Bengal Language, written at the behest of Governor General Warren Hastings (1732-1818), was published in 1778. This was a much fuller treatment of the language, and demonstrates Halhed's full grasp on what should be the components of an academic grammar. And it also carried the first experiments with movable Bangla types, whose shapes were curved by Charles Wilkins (1749-1836) and his Bengali assistant Panchanan Karmakar. Bengali printing would see its formal inauguration in this book and would begin being independently used in about two decades.

The third notable grammar of Bengali would come from the hands of yet another Englishman, William Carey (1761-1834). He came to India as a Protestant missionary, but, noting his inclinations, he was later entrusted with some academic responsibilities by the East India Company or the Governor General (1798-1805), Lord Wellesley, who founded Fort William College in 1800. Carey served the college as the head of the department of its Indian languages teaching program, and in the course of his work, wrote a Bengali grammar, a book of Bangla conversation, and a dictionary of the language. Moreover, he prompted others to write Bangla textbooks, to be published by the college.

Carey was also a polyglot and, in addition to that, had grown a special love for Bangla because of its relative 'closeness' to Sanskrit. The first Bangla textbooks, as well as those in other Indian languages, were written under his direction and published by the college, but they were mainly for the young Englishmen who had come to serve India as civilians. Carey, as we have said, has at least three important works that are closely connected with the teaching of the language. They are, chronologically, A Grammar of the Bengalee Language (first published in 1801, but later enlarged and revised to be republished in 1805), a book of Bangla dialogues, Kathopakathan (1801), and a table-size dictionary of English and Bengali (combined volume 1825). His grammar was also later translated into Bangla, in which Mrityunjay Vidyalankar (1762-1819) had a hand. Carey, of course, also wrote grammars of Marathi and Sanskrit.

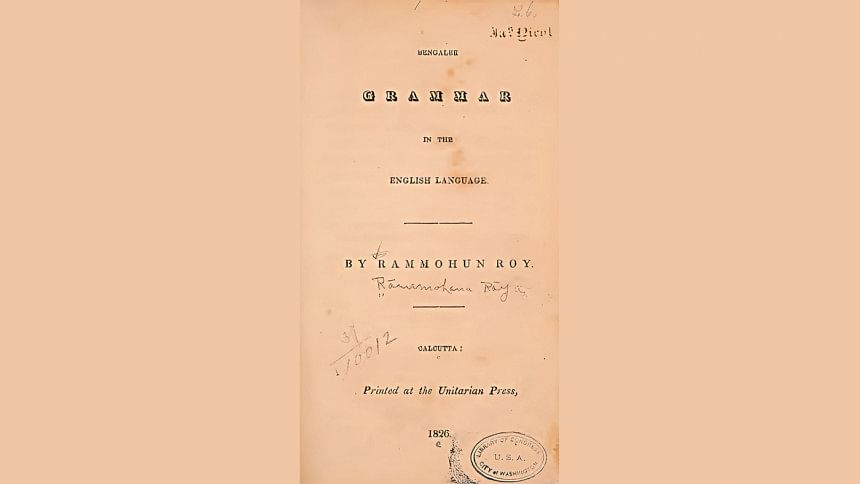

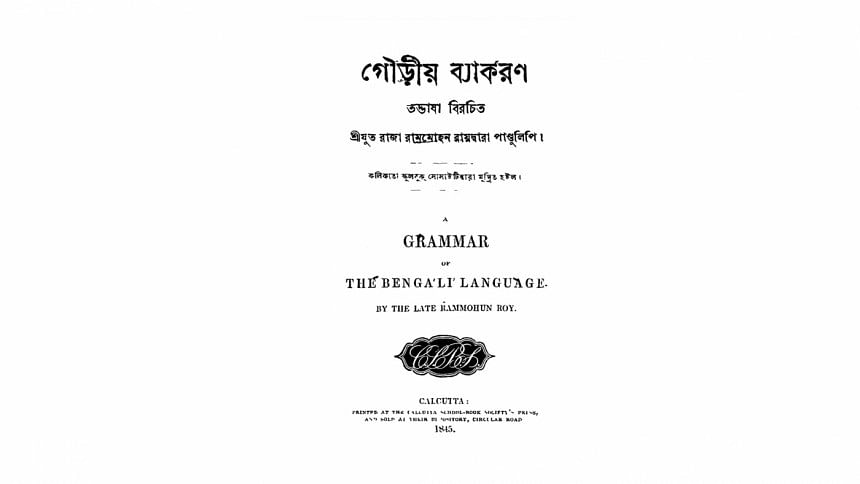

In 1801, the Russian adventurer, Gerasim Stepanovich Lebedev (1749-1817), also published a fragmented Bangla grammar in his A Grammar of the Pure and Mixed East Indian Dialects. Later in the same century, as well as in the next, quite a few Englishmen (and others) would write grammars of Bangla, but Rammohun Roy intervened to become the first Indian and Bengali to write such a grammar, first in English (1826, called Bengalee Grammar in English Language), and then in Bangla (1833, called Gaudiya Byakaran, tadbhasha-birachita).

3

When a grammar of Bangla is written in English, the Bengali reader's access to it is limited, and the authors know it. They write it mostly for users of English, Englishmen in general. These readers do not come to the language with any basic command of it and have to learn everything from the bottom up—the pronunciation, word formation, sentence formation and sentence patterns, correct usage, speech manners in appropriate social contexts, and the intricate rules of writing—from the alphabet to the orthography. A grammar written in Bangla for the Bengali audience may, on the other hand, have a different focus. I want to add that this may not always be true, as ancient models (Sanskrit or Latin, for example) often dominate and control the author's outlook, and a straitjacket frame is often adopted.

It is true that Rammohun's grammar was shaped on a Sanskrit model, but had an originality of outlook and a fresh approach. Das (1407 BE, pp. 135-6) gives an outline of the personal and social background which prodded Rammohun to write the grammar. The English version begins with a short discussion on the origin of human language, prompted probably by his exposure to the early deliberations of the Indo-Europeanists like William Jones. But his definition of a grammar sounds strikingly modern—"Grammar explains the principles on which conventional sounds or marks are composed and arranged to express thoughts." We will, however, focus on the Bengali version more, in order to underscore the originality of his approach. The Bangla grammar was, of course, written for a Bengali audience, for which the author could assume some native command of the language on the part of the user. But, as we know, in the grammars of the time, the Standard Written Bangla or the Sadhu Bhasha was emphasized, which was not a spoken form, so preference was almost always on how to write that 'chaste' variety. The author thought that that would benefit all Bengalis, including those who spoke a local dialect at home.

4

Let us say at the outset that we have consulted the 1845 text available on Google, which consists of 116 pages in total. Other editions are also available. For a grammar of a language, it looks quite small, unless it was intended as only a primary sketch. The publisher is the School Book Society, which the East India Company founded in 1817, with David Hare (1775-1842) at its head. Rammohun could barely submit his manuscript before he left for England in 1830, and due to his death there, he could not attend to its printing and publication. It was probably David Hare who took great care to have it published, as the preface mentions.

The grammar contains 38 prakaranas, or 'topics', organized sequentially, which are subsumed under 10 adhyayas, or chapters. One who has a basic notion about the structure of a grammar knows that a traditional one consists of sections like phonology (discussion of sounds in the language), morphology (how the sounds are combined to build meaningful forms like words, etc.), and syntax, in which the rules of making sentences are dealt with. In modern 'linguistic' grammars, other sections are added, but it was, naturally, far from being the practice then. And we must remember, instructions on writing were an important component. Rammohun follows the general pattern of the Sanskrit grammars and hence adds a further section on prosody.

A detailed discussion of the prakaranas will be too much for the uninitiated reader. We will therefore mainly focus on what distinguishes this grammar from others. The author was always keenly aware of the distinctive pronunciation of Bengali. He takes pains to tell us that all letters of our alphabet are not pronounced in Bengali speech, nor are they needed to be written outside of 'Sanskrit' words. He points out how two ja-s, na-s, and three sha-s are pronounced almost alike. After locating contexts where sha is pronounced as s, he also lets us know about the practice of Muslim Bengali writers to write Musalman with a chha, in place of a sa. It is quite noticeable that he dispenses with the Sanskrit sandhi rules, which, we think, should never have been a part of a Bangla grammar.

He, however, follows the traditional Sanskrit grammar in emphasizing morphology (twenty-one topics in all) or word formation and their roles in sentences. For the notion of 'person,' he uses prathama, dvitiya, and tritiya purush, by translating the English system, which looks much more reasonable than uttama, madhyama, etc., which were added later to the confusion of learners. He discards the so-called Sampradana Karaka, in which he was, again, quite ahead of his time. Syntax (anvaya) is dismissed in one topic, and so is prosody. Neither shows much light on the processes that had by then grown historically as quite complex systems.

He makes some innovations in terminology, which strike us as very original. For example, he regards a verb as an adjective. Only in twentieth-century grammatical thought was a close derivational relationship between verbs and adjectives critically discussed, so we are somewhat taken aback by his prescience. Still, we think that the two cannot be merged into a single category, as, syntactically, the verb plays a totally different role from that of an adjective. However, his postulation of four karakas for Bangla, to the exclusion of those of Sampradana and Apadana, is once again quite acceptable from a modern standpoint.

To sum up, one can say that this grammar, although it followed the Sanskrit framework, was written with a keen sense of the distinctive features of Bangla and shows a deep appreciation of the structure and function of the language as it had evolved till then. It is an unfortunate fact that this emphasis on the Bengali-ness of Bengali was ignored in most of the later school grammars, which almost put Rammohun's grammar out of use.

The best compliments for the grammar come probably from none other than Sukumar Sen, who says, "As this grammar was on hand, that is probably why Vidyasagar did not attempt to write any grammar of Bangla."

Major Sources consulted:

Bagal Jogesh Chandra (ed., 1361 BE, (see Chattopadhyay, Bankim Chandra)

Chattopadhyay, Bankim Chandra, 1361, Bankim Rachanabali, Calcutta, Sahitya Samsad.

Das, Nirmal, 1407 BE, Bangla Bhashar Byakarn O Tar Kramabikash, 2nd Editon, Calcutta, Rabindra Bharati University.

De, Sushil Kumar, 1961. History of Bengali Literature in the 19th Century, Calcutta, Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

Roy, Rammohun, 1845, Gaudiya Byakaran, (copy available from the Internet);

Pabitra Sarkar is an author and former Vice Chancellor of Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments