Historian Willem van Schendel divides the historiography of the War of 1971 into two broad categories: i) first-generation historiographies and ii) second-generation historiographies. The first-generation historiographies are too simplistic in nature and less sophisticated. There are mainly three principal narratives in this type of historiography: a) national triumph; b) betrayal and shame; and c) the glorious campaign. The authors of these narratives engage with the event to meet their own nationalist objectives. The first kind of narrative centers on the idea that the War of 1971 was a Bengali war of emancipation and portrays the sacrifices and valor of the Bengali nation, particularly the heroism of the middle class. The second type of narrative is written by Pakistani historians, who, in line with the ruling class of Pakistan, see the War of 1971 as an act of betrayal and refuse to accept the legitimacy of Bangladesh. The third narrative is mainly by Indian historians, who see the War of 1971 as a glorious campaign. This narrative also downplays the role of Bangladeshi freedom fighters and presents Indian forces as the chief power that offered independence to Bangladesh and freed its people from Pakistani repression.

It was neither the student group nor the middle-class leadership that first challenged the Martial Law Authority in East Pakistan. British High Commissioner J.S.P. Mackenzie, stationed in New Delhi, reported in 1959 that the working classes in East Pakistan posed a serious challenge to Martial Law authority in the state.

The second-generation historiographies, according to Schendel, are more sophisticated and inquisitive, exploring diversified themes. For instance, Nayanika Mookherjee's 'Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and the Bangladesh War of 1971' and Yasmin Saikia's 'Women, War, and the Making of Bangladesh: Remembering 1971' delve into the neglected themes of gender, violence, and public memory. Despite this, histories of the War of 1971 often lack proper representations and agency for subaltern people. Few historians place the working classes and peasants at the center of their narratives, with Badruddin Umar being a rare exception. However, almost no historians have studied the struggle of the non-industrial urban poor workers in East Pakistan in the 1960s and during the Liberation War of Bangladesh. This brief essay aims to shed some light on the struggle of urban menial workers during the 1960s and 1971.

Besides ideological bias, one of the reasons why historians often overlook the struggles and lives of poor menial urban workers in East Pakistan is the scarcity of sources. Most archives focusing on East Pakistan during the sixties and 1971 remain silent regarding the plight of the poor urban workers. Anthropologist and historian Ann Laura Stoler, in her work 'Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense,' argues that archival production is a consequential act of governance. Archives related to the Liberation War of Bangladesh, such as the Bangladesh Liberation War Museum and Genocide Museum, patronized by the Bangladesh government, primarily preserve, curate, and display records that reflect government or elite middle-class ideologies and interests, often neglecting the working classes or informal urban workers.

In September 2023, I stumbled upon a rare and well-preserved archive, neglected within a comparatively less popular department of the National Archives of Bangladesh. These fragile pages of archival documents shed light on the mobilization, protests, and struggles of urban menial workers in Dhaka during the 1960s and 1971.

East Pakistan witnessed a revolutionary upheaval in the 1960s. Historian Subho Basu asserts in his work 'Intimation of Revolution: Global Sixties and the Making of Bangladesh' that revolutionaries in distant East Pakistan used to read revolutionary texts published in different parts of the world and were inspired by revolutionary activities in Indochina, Cuba, and Africa.

During the 1960s, under military bureaucratic capitalist development, there was exponential growth in industries and working classes. However, Basu demonstrates that this capitalist development created growing economic and social discrimination between the two wings of Pakistan. Basu refers to this economic development under the military-bureaucratic regime as praetorian capitalism.

Under the praetorian colonial racial capitalism that developed in East Pakistan from the late fifties to the late sixties, peasants, working classes, and middle classes faced significant challenges. Alongside the democratic movements led by students and middle-class leadership, there was powerful activism among the working classes in East Pakistan.

It was neither the student group nor the middle-class leadership that first challenged the Martial Law Authority in East Pakistan. British High Commissioner J.S.P. Mackenzie, stationed in New Delhi, reported in 1959 that the working classes in East Pakistan posed a serious challenge to Martial Law authority in the state. In his letter to A.G. Wallis of the Ministry of Labour and National Service's overseas department on February 21, 1959, Mackenzie noted: The Martial Law Authorities in Pakistan just had the first serious challenge to their authority. Not surprisingly this occurred in East Pakistan, in the Adamjee Jute Mills at Narayanganj near Dacca. This is the largest industrial unit in East Pakistan, employing 21,000 workers and has previously been the scene of industrial trouble mixed up with politics… This recent trouble has been nothing like so serious but in the context of the Military Regime it is a most important incident.

The Martial Law authority took heavy-handed measures to quell the strike. Major General Umrao Khan, the then East Pakistan Martial Law Administrator, reminded the mill workers that all sorts of strikes and mobilizations were illegal under the Martial Law regime. He also announced the arrest of nine key leaders of the workers. General Khan admonished workers, stating that if any further trouble occurred, he would take severe action to punish the 'troublemakers.' The British diplomat Mackenzie observed that the strike seemed as spontaneous as the trade union was inactive then. Strikes like this, or more intense, were not uncommon in the Sixties in East Pakistan.

What remains relatively unknown are the strikes and mobilizations led by the urban informal workers of East Pakistan. Throughout the Sixties, the scavenging community in Dhaka and other major cities orchestrated powerful mobilizations to advocate for their rights and demands. The cleaning workers of Dhaka formed a robust and active union, naming it the Dacca District Scavengers Union. Over the course of the decade, these cleaning workers consistently presented their demands through this influential union. Employing various tactics, the scavengers of Dhaka endeavored to assert their demands. Initially, they pursued a policy of submitting memorandums to municipal authorities, and even to the provincial government's leadership. When these memorandums failed to yield results, the scavengers resorted to more assertive actions, including processions, strikes, and picketing.

From 1967 to 1969, the Dacca District Scavengers Union repeatedly presented their demands to the Dacca municipal authorities and even to the president of Pakistan, resorting to short-term strikes during these years. The year 1969 proved to be particularly successful for the union. On March 19, 1969, the Dacca District Scavengers Union initiated an indefinite strike to underscore their 18-point demands. Among these demands, prominent ones included securing permanent employment status after three months of initial service, ensuring weekly holidays and various types of leaves (such as sick, festival, and casual), providing maternity leave for female colleagues, offering healthcare support, establishing a contributory provident fund, implementing a graded pay scale with incremental increases, ensuring adequate provisions for latrines and urinals in scavenger quarters and sheds, constructing additional quarters, and establishing primary schools for the education of their children, among others.

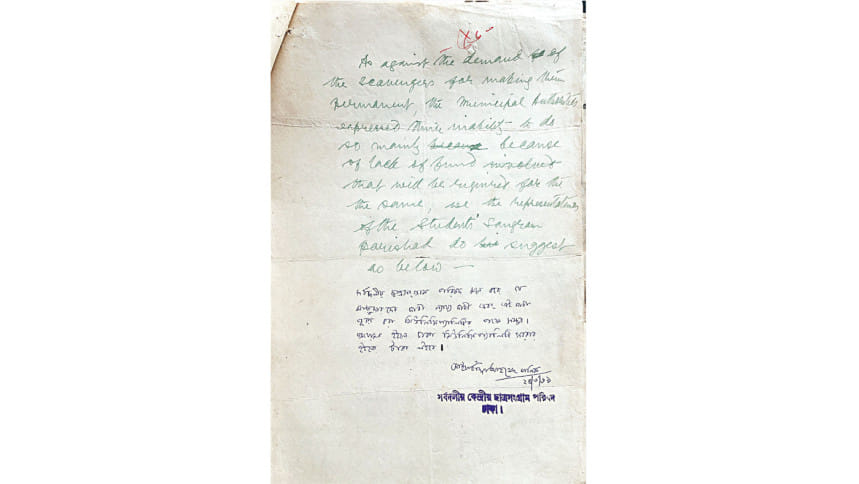

The strike in March 1969 was so effective and intense that the Dacca municipal office responded very promptly, and the municipal office had to sign a memorandum of agreement with the Dacca District Scavengers Union subsequently. Two days after the Dacca District Scavengers Union started their indefinite strike, an officer from the Dacca municipal office sent a letter to Gour Chandra Barman, the president of the Dacca District Scavengers Union. The officer from the Dacca municipal office wrote, "Dear Sir, Chairman Dacca Municipal Committee desires to meet you in a meeting in which some leaders of the student(s) organization have also kindly agreed to attend tomorrow at 10 a.m. in the Municipal Office to discuss about the demands of the Municipal Sweepers. I would request you to kindly make time to attend the meeting with your General Secretary and a few others as you may think necessary. Thanking you."

From the municipal office letter, it appears that the Dacca municipal office wanted to keep some student leaders as negotiators, as we may assume that the Dacca district scavengers had a good relationship with the student leaders. A solidarity letter from the Sarbadalio Kendrio Chatra Sangram Parishad, Dacca, a spearhead of mass upsurge in 1969, affirms our assumption. Signed by Saifuddin Ahmed Manik, one of the important leaders of the student body and later became a prominent communist leader, the letter reads: "Sarbadalio Chatra Sangram Parishad believes that the demands of the scavengers are rightful, and municipality can fulfill these demands. If needed, the municipality should seek money from the government." In the sixties, the middle class and student leaders tried to mobilize urban workers and the poor in the nationalist and democratic movements. In return, student and middle-class leaders offered solidarity to the movement of the urban poor workers.

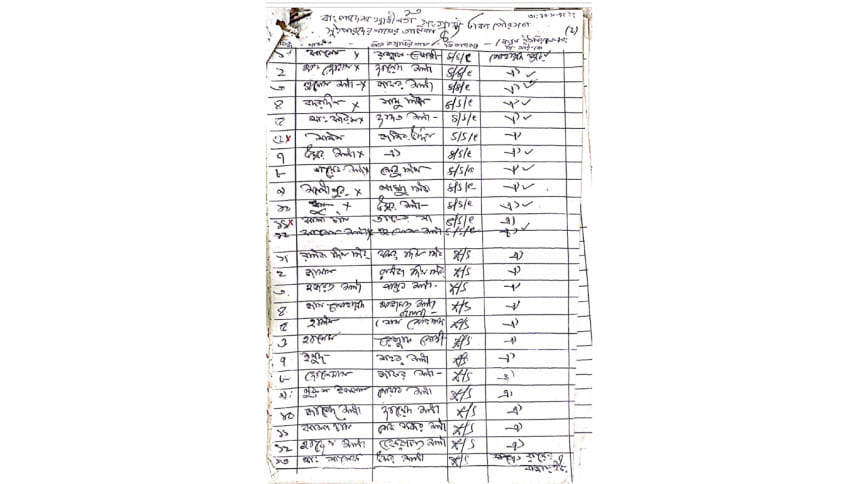

In 1971, when many government officers and university teachers opted to work and collaborate with the East Pakistan government, the scavengers of Dacca under the Dacca District Scavengers Union left their jobs and most of them left Dhaka. Many of them joined the liberation war and fought for the country. After Bangladesh's victory on December 16, 1971, the scavengers of Dhaka returned to their job. The Dacca District Scavengers Union made a long list of the scavengers who left their job during the liberation war of Bangladesh. The Scavengers Union submitted the list to the government to demand their wartime wage. A few names from the long list are: Jamila, Sayara, Mehrun Nesssa, Ramijuddin, Julhas, Hazrat Ali, Jamshed, Upendra, Abhoy, Bejoy, Ashit, Binod, Rajendra, Susil, Nitai, Bimal,Priolal, Bijendra, Dhanu Miah, Nayeb Ali, and so on. The Dacca District Scavengers Union also prepared a list of the scavengers who participated in the Liberation War of Bangladesh. The title of the list is the List of the Swadhinata Sangrami Sweeper (the list of the freedom fighter sweeper). The list consists of 66 names. Some names are Kalu Mian, Kala Chan, Udhbav Shil, Demru, Ramuna Anna, Dayal Hori, Siddiq and so on. Unfortunately, we do not get any list of the martyred cleaning workers.

In his 1995 book Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, reputed anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot demonstrated how power and representations engineer people's understanding of history and thus, produce silences. The dominant historiography of the Liberation War of Bangladesh silenced the voices of poor urban workers and erased their names systematically. The essay is an attempt to show how urban menial workers were active in democratic and right-based movements in the revolutionary sixties and the Liberation War of Bangladesh.

Azizul Rasel is a PhD scholar at McGill University, Canada.

Comments