SM Sultan: An early portrait

These are the facts of Sultan's life that have significance for the study of his paintings. He spent his boyhood in the villages of Bengal. He got some academic training in art at the Calcutta School of Arts, as a precocious young lad but left without completing the discipline, and has ever since been wandering all over the sub-continent. He may be said to have no formal education of any kind but has gazed with wonder and admiration at the reproductions of modern masters without of course understanding the technical and aesthetic revolution that they represent. He has eked out a precarious living with pencil and brush and knows no other trade to support himself. He can never bring himself to doing commercial art work, besides the fact that he is too erratic for business dealings. The result is that he has lived a life of poverty broken by short spells of prosperity and improvidence. Since the years of his growth coincided with the war, it happened that he found his greatest clientele among the British army officers who wanted to take mementos from the country. Moving in these circles of foreign art-lovers and artists, he could not help being influenced by many of their ideas and tastes in art.

It is not to be thought that the above is like the premise of a logical syllogism from which only one conclusion will follow. In fact a person placed in such circumstances could paint in a variety of ways. It is quite likely that he should have started to paint spurious imitations of old Mughal paintings which had high market value as curios during the war. But Sultan had that in him which was seeking expression; mechanical "picture making" was not enough for him. Every artist paint both to please himself and his clients; now though the latter consideration was very urgent for Sultan, it does not mean that he did not choose the style which was most congenial to his temperament. Like every young artist he has thrown about for the nearest ready-made style that can express his personality. It is only after the dissatisfaction grows on him that these styles do not convey exactly what he means to say, that he forges a new path for himself. Sultan is slowly emerging into this stage.

Sultan has no collection of his old works for he sells out everything. I do not know therefore what he painted before Pakistan was established, except that he had painted a great deal and that from life; but ever since, he has been painting mostly landscapes of Bengal and Kashmir. Now he has been away from Kashmir for four years and from Bengal for about twelve. Almost all his landscapes therefore are done from memory. Inevitably they are somewhat idealised and somewhat sentimental, especially when the local folk figure in the scene. Both these qualities I guess were acquired when he was painting for foreign visitors. Again the choice of style must have been dictated by the need to paint quickly. Sultan has incredible facility and neither can nor does sweat over a painting for any length of time. His mercurial restless nature has much to do with this. The result however is that he never aims at finish and practises some sort of impressionism in his better works, while the rest are just quick sketches.

THE DIFFERENT STYLES

Let us consider his works more closely to find their distinctive qualities. What I think impresses the spectator most is the bewildering variety of his styles. There are first the soft subdued tones of his panoramas of Bengal done in water-colour, depicting wide expanses of water and sky, the melting horizons, palm trees and boats, fisher-men and dainty huts, in a charmed atmosphere of rustic serenity. Thin, watery, flat!

Then there are panoramas of Kashmir, mostly in oils, all richly colourful, almost flamboyant--the deep purple mountains, the variegated shrubbery and trees, the lakes and rivers, which make up a scene very unlike the unrelieved monotony of Bengal.

Both the above group of pictures are heavy with literary interest—the non-artistic interest of describing notable objects and interesting landmarks in the scene, more to establish their identity than to exploit their artistic value for studies in form and colour, integrated into a purposeful design. The authenticity of a convincingly built up structure, in details and in the whole, is lacking, partly because it is not based on immediate observation and partly because panorama reduces form to its most tenuous, and makes the interplay of light on broad spaces the main subject of the painting.

There is more however to Sultan's work. There are close-ups, landscapes in water colour, showing a patch of vivid green, a copse, even a single tree with all its fascinating chiaroscuro. These are executed with an eye to the evanescent effects of changing colour on the foliage and on the shade. The execution is marked by verve, for such a subject requires not meticulous draftsmanship and careful graduated washes, but deft suggestive touches that help the mind to reconstruct reality in all its quivering intensity of life and movement. Not only is it a better interpretation of the personality of the tree but as a pattern of line and colour, light and shade, it is on a much higher plane.

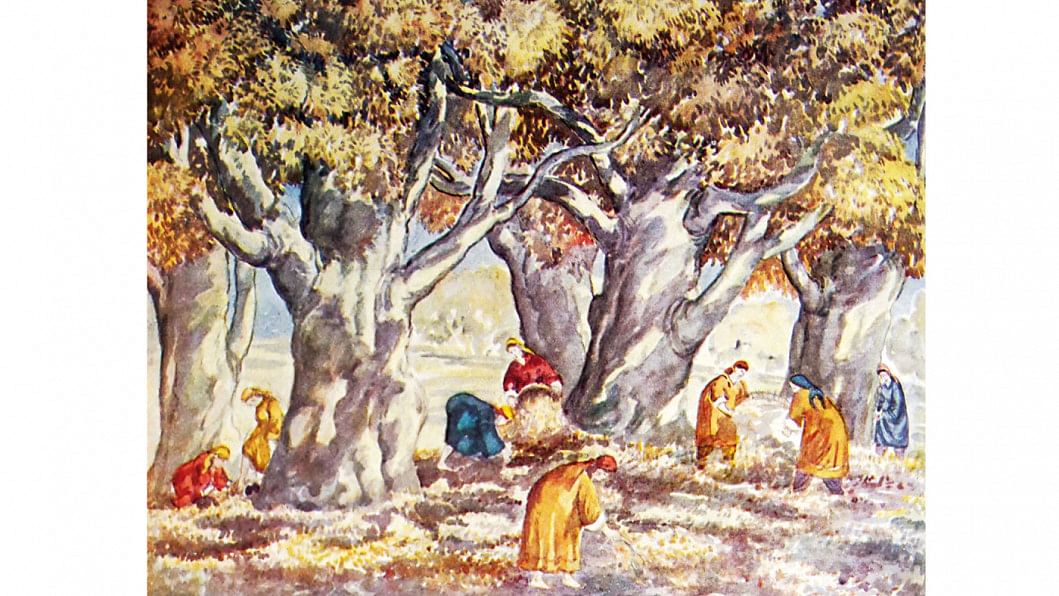

While in the above Sultan throws planes, direction, and form overboard in a mad love of colour and harmony of tones, this is far less true of the remarkable little landscapes he has done in oils, specially those done with the knife. There is better understanding of the plastic significance of the subject, the relation of the depth and surface, the total build-up of the values. No smooth suave surfaces here, but telling daubs of fat thick colour, sonorous tones. The different shades of the same colour are sensitively juxtaposed to create a vibrant quality; different colours are placed together to build up a convincing structure as well as a flawless, singing harmony. For, as Cezanne, said "When colour has reached the maximum richness, form is at its zenith". There is no mere literary interest in these paintings. The hills and dales, the rocks and trees, are but pretexts for a study of form and colour and the expression of personality. Most of the above remarks apply to those of his water colour studies in which he has left the patchy sketchy style for the more finished though still impressionistic manner-as in his rich and mellow autumn scene, which I consider his masterpiece. It has excellent modelling, remarkable tonal harmony, and a satisfying design. It has verisimilitude also. On a lower plane in this style is another Kashmir Scene, which is mainly remarkable for design. Excellent again is the study of Kashmiri women under walnut trees. The foliage is somewhat stylized--it is never very realistic in Sultan-but the trunks are architectonic in their solidity. Perhaps some day when he had more time on his hands, Sultan was carried away into a loving study of detail, away from fleeting impressions into the world of consecutive vision. The result is the marvellous painting of autumn in Kashmir with a house boat in the foreground. It is a wonderful pattern, and the turning, twisting branches are almost symbolic in their rich significance. As a composition in space too it is skillful and true. The execution strikes a happy balance between perfunctory sketch and laborious finish which can make even a non-impressionistic painting a pleasure for modern art lovers to see.

It only remains to point out that Sultan is not a mere landscape painter. He has made excellent study of the human figure and I have seen both drypoint sketches and large crayon studies by him which show a very high degree of merit. However, what came as a pleasant surprise was that he has recently done two large panels showing crowds of refugees and poverty-stricken multitudes. The delineation of the human forms is admirable and the composition is marvellous. The severe selectiveness of the lines of human figures, the largeness and boldness of the composition, and above all the human interest and tragic note in these panels are welcome signs of growth and maturity. I think Sultan has won his spurs in the field of technical skill and what he needs now is contact with great ideas and some rich experiences of life and art, to produce masterpieces of painting. His present visit to America under the International Education Exchange programme is a step in the right direction and likely to prove very fruitful.

S. Amjad Ali was the editor of Pakistan Quarterly.

Paintings: SM Sultan

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments