Kalaketu, a hunter belonging to the lowly Kirāṭa community, is the hero of the Ākheṭik Khanḍa (Book of the Hunter) of Mukundaram Chakrabarti's Canḍīmaṅgal (c.1579). Along with his wife Phullara, Kalaketu ekes out a meagre existence by hunting and selling forest products in local markets. One day, Goddess Canḍī visits the couple and chastises them for slaying the other animals of the forest, who are also under Canḍī's protection. She blesses Kalaketu and Phullara with a lumpsum and orders them to clear the forest in nearby Gujarat and establish a kingdom there. This initial wealth attracts many day-laborers and erstwhile forest-dwellers to the region. By their unremitting toil, a city and market are founded.

It proves difficult, however, to get people to settle down in the city. Kalaketu again seeks Canḍī's help, who floods the neighboring kingdom of Kalinga, but even that does not lead to immediate migration. Residents of Kalinga decide to make Gujarat their new home only when their king insists on collecting all taxes even after the flood, and when people hear that Kalaketu offers tax-free settlement for seven years and charges no extra levies on festivals, salt, and police protection. Once Kalaketu's modality of rule becomes common knowledge, his kingdom flourishes in no time, but with that comes new problems.

in the duty-free market with contempt. Bhām̐ṛu steals and tries to exact duties from Kalaketu's subjects, even beats them if necessary, despite having received rent-free lands himself. Upon receiving complaints from his subjects, Kalaketu banishes Bhām̐ṛu from Gujarat and the headman becomes intent on exacting revenge. He goes forthwith to the king of neighboring Kalinga and warns him of the upstart lower-caste king in Gujarat. Bhām̐ṛu reports that Kalaketu's people live in harmony and wealth is produced at a fast pace. If this is allowed to continue, Bhām̐ṛu says, then Kalinga will soon be deserted!

The king of Kalinga is furious and exclaims that there cannot be two kings in one kingdom! He begins a war with Kalaketu, which the latter eventually loses despite initial victories. The king has half a mind to execute Kalaketu but decides to imprison him at the request of the courtiers who suspect that Kalaketu is merely Canḍī's vessel. Indeed, it is only Canḍī's divine intervention that gets Kalaketu out of jail and revives the lives of all those who had fallen in battle. Bhām̐ṛu Datta is punished for his misdeeds, and Gujarat returns to its erstwhile vibrant and flourishing state.

Fast forward two centuries. January 1778. Calcutta. The Kayastha Raja Nabakrishna Deb (1732-1797) complains to the British colonial state that petty merchants and shopkeepers (tahbazaris) have been deserting his legally established market. The tahbazaris have been provoked, Nabakrishna insists, by the upstart Madan Dutt, who has dared to establish a market on his land without a charter issued by the state! By the customary law of the land, Dutt's market should, therefore, be immediately abolished.

The company-state is unsure about the best course of action. Its confusion is compounded by multiple petitions from the shopkeepers, vendors, and landowners of Sutanuti against Nabakrishna's depredations. In light of myriad grants bestowed by the government on the Raja since the early 1770s, the petitioners fear for the "security" and "liberty" of their property and the ability to dispose of their property freely. They plead for such liberty to be granted to them by the government and bemoan the "arbitrary" authority and "unjust" exactions of Nabakrishna.

The Raja, for his part, doubles down and swears that the petitioners against him are largely "poor" and "ignorant," and that the "highest" inhabitants (of the city) with a "better" disposition have not petitioned against him. Nabakrishna also reminds the state that he dutifully pays taxes and that no government in Bengal has ever allowed a private landowner to establish a market without a legal charter and customary taxation.

A lengthy legal battle ensues and lasts the whole year. Madan Dutt argues that he simply rents out land, which is his private property to do as he pleases. The shopkeepers and tahbazaris claim that they rent land from Madan Dutt because the duties in Nabakrishna's market are five, ten, or even fifteen times higher! Indeed, many shopkeepers argue that Dutt has not established a market at all, because neither the dām (a duty in money on each shop) nor the tolā (a duty in kind on the articles of sale) are collected on Dutt's land. The transaction between Dutt and his tenants is between two private parties freely disposing of their property, to which neither the state nor Nabakrishna should object.

It's December 1778, and the state is unable to prove either that Madan Dutt is occupying the land illegally or that he is surreptitiously collecting duties. Company officials agree that these are private transactions and a man may let his land for whatever rent he can get. Unable to find a legal principle to abolish Dutt's "market," the state falls back on a consequentialist argument: Ifsuch actions go unpunished, then the state and local persons of authority (such as Nabakrishna) will gradually lose their property right over the disposal of property! In January 1779, based on this thin argument, the state orders that the shops on Dutt's ground be razed. Property is thus destroyed in the name of property.

Reflect, for a moment, on the uncanny similarity between these two stories. If we ignore the constant presence of divine agency in Mukunda's Canḍīmaṅgal and its upbeat ending, and then replace Kalaketu with Madan Dutt, Kalaketu's subjects with the tahbazaris and shopkeepers on Dutt's land, Bhām̐ṛu Datta with Nabakrishna, and the king of Kalinga with the British East India Company, we arrive at the structure – albeit not the exact content – of the legal battle of 1778. The similarities in structure and motivations are undeniable, and Bhām̐ṛu Dutta and Nabakrishna Deb hail from the same caste! Is this a mere coincidence?

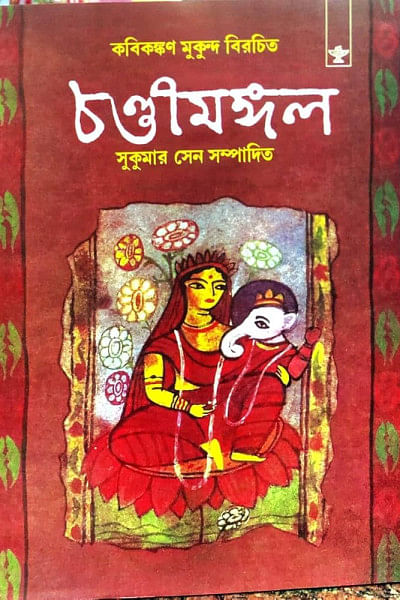

I think not. Mukundaram's text belongs to one of the most distinctive genres of medieval Bangla literature – the Maṅgalkābyas (literally, "poems of well-being") – composed between the late-fifteenth and early-nineteenth centuries by the rural, relatively poor Brahmans of south-western Bengal. Scholars of these texts have noted that the Maṅgalkābyas present a complex picture of the contemporary social landscape, and they ruminate on the possibility of subaltern actors challenging caste and gender norms. Moreover, the problems discussed in Maṅgalkābyas often referred to actual historical ones, and the audience was expected to actively engage with and evaluate the logical and ethical valence of arguments made by the characters.

If this is true, then it follows that a basic socio-political problem in early modern Bengal – that those with substantial property and authority exercised a property right over the disposal of other people's property – was neither restricted to urban settings like Calcutta nor radically new in 1778. Even in rural western Bengal – where the Maṅgalkābyas were performed – the problem was important and recognized as such. Otherwise, it could hardly have found such a clear expression in Mukunda's text.

We can go even further to link the social and economic contexts of the two stories. Bengal underwent major socio-economic as well as political transformations between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Vast amounts of fallow and forest lands were brought under the plough with remarkable vigor, first in the western and south-western frontiers of the province in the sixteenth century, and then in the east throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This was paralleled by the expansion of marketing and the establishment of new markets, and some of the markets founded in the late sixteenth century were still functioning two centuries later. In short, the stakes of being able to access land and markets more freely increased dramatically. Unsurprisingly, this led to caste struggle, since the control of access to land and markets – along with the regulation of sexuality – had always been the practical basis for reproducing caste hierarchies. Indeed, the efflorescence of Vaishnavism in sixteenth-century Bengal should also be read against this historical background.

The eighteenth century, of course, witnessed the rise of an extractive colonial empire after 1765. As a result, scholars often tend to read all events after that date as bearing the stamp only of colonial power. I have argued elsewhere in detail, however, that the conflict of 1778 cannot be reduced to the question of colonial governance. While the impulses of the revenue-hungry state demonstrate its illiberal character, the critique of arbitrary exactions must be read as a critique of practices that reproduced caste. Close attention to the history of settlement in Calcutta and clues thrown up by the colonial archive – such as Nabakrishna calling his opponents poor and ignorant – allow us to conclude that the tahbazaris of 1778 belonged to middling and lower castes. Nabakrishna was a Kayastha, one of the three elite castes of medieval Bengal along with Brahmans and Vaidyas, and his tendency to act in authoritative and extractive ways embarrassed even colonial officials at times. Although Madan Dutt was a wealthy businessman (his caste background is unclear), Dutt's social status cannot explain the sustained political struggle of the tahbazaris.

The history of caste and caste struggle, in short, cuts across the colonial/pre-colonial divide. Socio-cultural transformations from the sixteenth century onwards inspired critiques of caste, and those worst affected by "arbitrary" impositions challenged their legitimacy. In Calcutta, aspirations for alternative institutional arrangements took the form of unprecedented commercial cooperation between peoples of multiple ethnicities, and the Calcutta Mayor's Court established in 1726 sought to model itself on the legal culture of the Atlantic colonies. The city became a refuge for people fleeing the arbitrary exactions of landed elites and the Bengal Nawabs, and evidence from the conflict of 1778 shows that in the years leading up to 1765, many South Asian merchants allied with the radical bourgeois faction within the East India Company that sought to establish a liberal commercial order in Bengal.

A bourgeois revolution, therefore, was once an incipient political possibility in Bengal, and the contingent failure of this possibility explains the illiberal character of the post-1765 empire. Kalaketu's story in the Canḍīmaṅgal and the conflict of 1778 show us that precisely because the stakesof an open marketplace were large and recognized as such by subaltern actors, caste struggle found an ally in the radical bourgeoisie. Historians of South Asia have either failed or been reluctant to chart such aspirations and the political alliances they gave rise to, preferring instead to see liberal modernity as either a colonial imposition or a matter of concern only for elite figures such as Rammohan Roy. It is time to ask why this has been the case and to go beyond the inadequate historical memories that have been bequeathed to us. The nineteenth century certainly marks a violent break in our history, but we cannot recognize the stakes of this break if we do not understand the nature of the social and political possibilities that were closed off by illiberal colonialism.

Anirban Karakis a Collegiate Assistant Professor in the Social Sciences Collegiate Division at the University of Chicago.

Comments