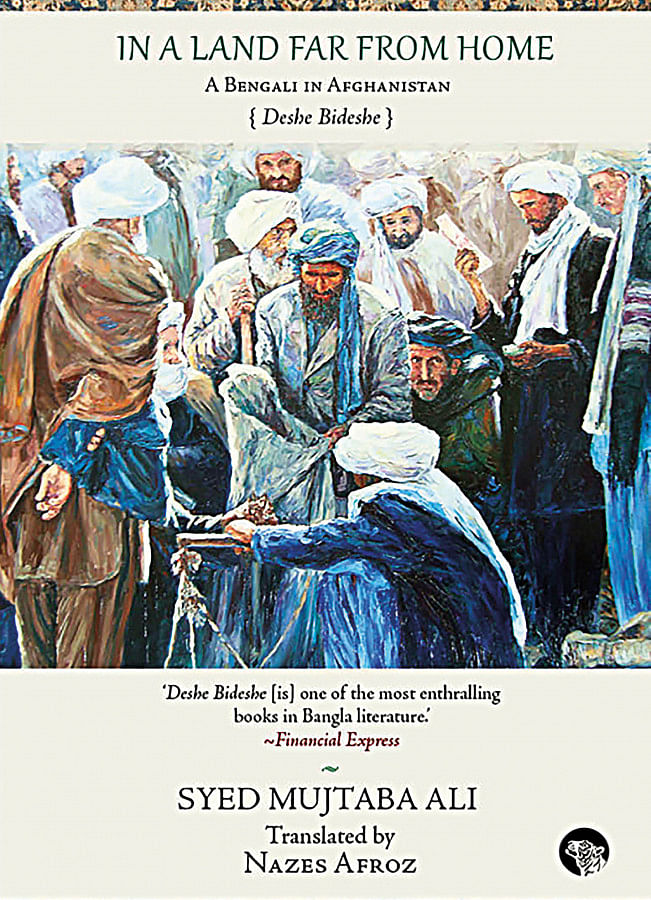

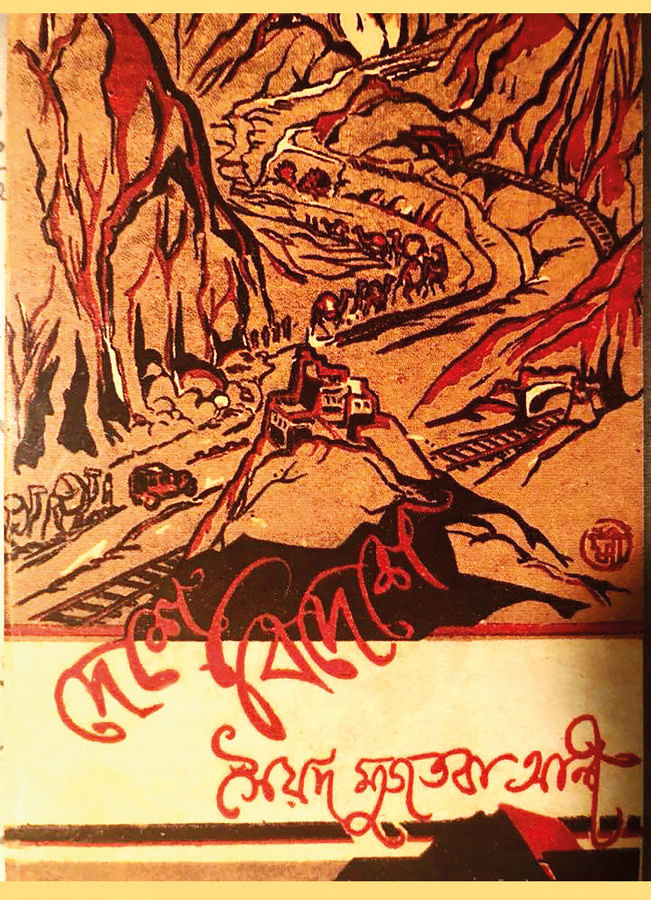

Syed Mujtaba Ali between Bengal and Afghanistan

Historically, Afghanistan, and its cities Kabul and Peshawar, were central in the Mughal imagination as the space where the idea of Hindustan took shape. Bengal, on the other hand, was the farthest eastern frontier. The province was conquered by Akbar almost at the end of his conquest of India, in 1576. For the British however, their territorial conquests in India were a reverse of the Mughals – Afghanistan on the west and Burma on the east were the last frontiers, while Bengal became the seat of British power since 1757. The western scholarship on Afghanistan tends to focus on the Anglo-Afghan relationship in the 19th and early 20th century, and foregrounds conflict between Afghan and British competing motives in what was presumably the first Cold War. This was more well-known as the Great Game, a series of Anglo-Russian diplomatic maneuvers. These imperial games were further enlivened by the historical memory of the carnage faced by the British in the three Anglo-Afghan wars. Rudyard Kipling, in his famous novel Kim, focused on this imperial rivalry. These Anglo-Afghan wars, which frustrated British ambitions of expansion on the Western frontier of their Indian empire, were fought over eighty years from 1839-1919. One of the outcomes of these conflicts was the drawing of the Durand Line in 1893 across the Pashtun homeland - perhaps the first senseless Partition in the South Asian subcontinent.

However, with the disastrous British expeditions to Afghanistan in the 19th and early 20th century, the narrative about linkages between Hindustan and Afghanistan began to change. First the British and subsequently other Western imperial powers began to characterize Afghanistan and Afghans as "ungovernable." The fact that there were repeated failures of imperial control and that recognizably Western modes of statecraft never took root in Afghanistan, led to a silencing and erasure of the pre-colonial connections between India and Afghanistan in colonial records and narratives. This particular failure of the imperial western imagination when it came to Afghanistan, to point towards very recent history, gave us the two-decade long "War against Terror." The end of this war, and the sudden and devastating fallout in the region, is an ongoing concern for all South Asian nations, and for both the US and China.

We however get a different narrative about Afghanistan when we turn to our very own Syed Mujtaba Ali. When Mujtaba Ali made his life-changing journey from Calcutta to Kabul in 1927, almost a century ago, he was barely 23-years-old. His most precious possession was an M.A. degree from Rabindranath Tagore's Santiniketan - an educational qualification not recognized by the British administration as a valid degree. Mujtaba Ali would work at the new Education Department in Kabul between 1927-1929, which had been set up by the ruler of Afghanistan, Amanullah Khan. Amir Amanullah, in his short reign between 1919 and 1929, had gathered the reputation of a modernist reformer. Mujtaba Ali's journey across the breadth of the British empire into independent Afghanistan, would be the beginning of his life-long fascination with the idea of travel and of limits. It would inspire him creatively to invent a new genre in Bengali literature, that of "Ramya-Rachana" or belle-lettres.

His Kabul travelogue, Deshe Bideshe, was filled with historical observations on the slow decolonization processes across the world. It is in this travelogue that Mujtaba Ali would experiment and create an authorial self, that of the Bengali raconteur or addabaj. This addabaj would move out of the porches and teashops of Bengal and continue a flaneur-like investigation of urban spaces and cities, observing, walking and talking across the Indian Ocean arena and Europe. Mujtaba Ali's travelogues were cultural and social investigations of the world from the point-of-view of a colonized but cosmopolitan India, in the period leading up to the second world war. From the rise of Nazism in Germany (Chacha Kahini) to the world of Kemal Ataturk and Gamal Abdel Nasser in Turkey and Egypt (Jale Dangai), Mujtaba Ali would map shifting geopolitical equations in this rapidly decolonizing world.

We have to ask an important question about Mujtaba Ali's Kabul adventures - what did this experience mean to this young Bengali man? Mujtaba Ali's literary depictions of Afghanistan open up a complex and yet familiar land to the readers, which is affectionately rendered in beautiful yet light prose. In the opening chapters of Deshe Bideshe, as the train made its way across India, Ali recorded his reflections on his teacher, Gurudeb Rabindranath Tagore. Rabindranath's short story Kabuliwallah, written in 1892, was constantly on Mujtaba Ali's mind during this journey. For Rabindranath, the affectionate bond between the narrator's young daughter and the migrant Afghan small-goods trader in Kabuliwallah, collapsed the boundaries of difference between that foreign land and the well-known spaces of the middle-class Bengali home in Calcutta, through a powerful act of imaginative vision:

If I hear the name of a foreign land, at once my heart races towards it; if I see a foreigner, at once an image of a cottage on some far bank or wooded mountainside forms in my mind. High, scorched, blood-colored forbidding mountains on either side of a narrow desert path; laden camels passing, turbaned merchants and wayfarers, some on camels, some walking, some with spears in their hands, some with old-fashioned flintlock guns.

This literary technique, that of collapsing the boundaries between Desh and Bidesh, would be used by Mujtaba Ali extensively in the narrative of his own discovery of Afghanistan. From the perspective of Ali and other Indian travelers, Afghanistan in the early 20th century emerged as a truly cosmopolitan place of cultural familiarity. Kabul especially was a common space of engagement, through the intimacies of cultural, political and linguistic connections, where Indians could forge wider global anti-colonial solidarities. Afghanistan provided not merely the border, physical or mental, to the constrictive existence of a subject race, it provided a glimpse of a space which was ungovernable by the rules of colonialism. The shared locus of Indo-Islamic heritage and history, enlivened by years of creative accommodations of difference and existing trade routes, were only disturbed as late as the nineteenth century.

There are interesting historical possibilities of thinking about the valences of frontiers and homelands through a wider study of Syed Mujtaba Ali's considerable corpus of travel writing spanning all of Asia and Europe. I would like to position Mujtaba Ali's work as an entirely serious, and anti-colonial reimagination of the possibilities of existence beyond colonial control. In fact, Ali's travelogue is also the autobiography of a possibility of reform and modernization beyond imperial control. Mujtaba Ali took on the role of a flaneur, and that has often affected judgment of his work as merely light and amusing observations of peoples and places. I believe that humor and laughter, which Mujtaba Ali deploys with surgical precision in Deshe Bideshe, are in themselves techniques of recording what was to be a historical genre-defying work of Indian historiography for Indians. Ali's laughter destabilized the fundamentally colonial practice of travel as domination and travelogue as ethnography. Instead, he used the idea of Afghanistan as the homeland of a quintessentially South Asian culture, to flip the idea of colonial historiography on its head. Travel for Mujtaba Ali engendered kindness, liberality and empathy.

The Afghanistan/British India border – ungovernable to the British, and a space of strict codes of independent conduct for the Afghan tribes, was observed by Mujtaba Ali as a space for liberty, liberality and unrestrained mobility. Peshawar itself, the city of bazaars and gossip, would be for Mujtaba Ali, a foreshadowing of Afghan hospitality and friendship – a code of honor that went beyond the social niceties of polite conversation that Mujtaba Ali was perhaps used to in Santiniketan and Calcutta. The border, to an Indian traveler like Mujtaba Ali, was truly the cosmopolitan marketplace for exchanges of goods, information and hospitality. The journey through the Khyber Pass, physically demanding because of the extreme weather conditions and due to the lack of access by railways, remains one of the most vivid descriptions in Deshe Bideshe. And yet, Mujtaba Ali exhibited a joyful anticipation of reaching the gardens of Kabul. The border, Mujtaba Ali seemed to suggest, was a chimerical creation of the British – one haunted by labyrinthine and senseless paperwork and violence. But the code of hospitality between the people of Afghanistan and India was enduring and far more real. Mujtaba Ali's experiences in Kabul, at least for the first year and a half, are similarly joyful, enlivened with cultural and social exchanges, and discovery of linguistic and historical affinities between his home and the new world he inhabited. His connections to intellectuals and the Afghan aristocracy in equal measure, as well as access to the rumor economy of Afghan politics, through his servant Abdur Rahman, remain both a wonderful pleasure to read, as well as an invaluable eye-witness document of an important moment of change in Afghan society.

When tragedy set in, in this almost idyllic life-world, with the beginning of civil war in Afghanistan in 1929, Deshe Bideshe provides a poignant picture of a moment of terrible loss, a destruction of those possibilities of positive change. There are two instances of transcendent spiritualism in Deshe Bideshe – one at a moment of communitarian joy, and another at a moment of lonely terror. In the first, Mujtaba Ali visits his friend Saiful Alam's home for a wedding celebration. Saiful Alam, like many young aristocratic Afghans, was completely westernized and educated in Paris, but the wedding Mujtaba Ali depicted was traditional. It is at this wedding that Mujtaba Ali listens to the performance of a traditional Afghan Sufi singer. This old, wizened musician creates magic by singing a Farsi ghazal. "Shab-e Agar," he sings – just for one night – if his beloved kisses him only once - "Aaj lab'e yaar bosaye talbam." The singer conveys that he is prepared to suffer life all over, once again for one touch of grace from his beloved. Mujtaba Ali describes the feeling of listening to the music in the deepening night as an experience of synesthetic absorption. He notes that the listeners were shocked, enchanted, and as the notes emerged, he perceived them not as sound but as colors. For Mujtaba Ali, the love the singer expressed for his beloved, mirrored the love of Afghans for their difficult homeland. Therefore, the music was an illustration of that patriotism, a drowning in the soul of Afghanistan itself.

The second experience Mujtaba Ali depicted was one of unmitigated devastation. Kabul had been overrun by the outlaw bandit Bachha-i-Saqao's mercenaries. Saqao, the water-carrier or bhisti's son, would shortly crown himself as Amir Habibullah Kalakani, and oust Amanullah Khan and his family from Afghanistan. Mujtaba Ali, who had an unfortunate propensity to speak hard truths to those in power, had annoyed the British Minister in Kabul, Sir Francis Humphreys when he protested against the airlift rescue of Europeans from Kabul, while British Indian citizens were abandoned to the ravages of the civil war. As a consequence, he was struck off the list of Indians that the British bureaucrat would airlift to India, in the world's first air-rescue operation. In its last few chapters, Deshe Bideshe is a testimony to Mujtaba Ali's grief, not merely for the dangerous situation he found himself in, but also for the destruction of Amir Amanullah Khan's reformist program. That lost moment of possibility was indicative to Mujtaba Ali, and to his readers, of a different future for the Indian subcontinent – a possibility that would never be realized.

Though it is Bengal, and Sylhet, that were truly home for Mujtaba Ali – in an act of spatial and historiographical telescoping, he sets the most emotional scenes of the travelogue at the tomb of the Mughal emperor Babur. It is clear that he felt a profound kinship with the emperor. It is in this sanctuary, bent in prayer, that Mujtaba Ali describes his fear, his grief and his uncertainty, not only about his life in Kabul, but also about the future of India under British repression. It is a moment of supplication, of sajda, where Mujtaba Ali asks for "mukti, moksha, najaat" for both Afghanistan and Hindustan. This moment of acute empathy erases the distinction between homeland and frontier, both for Mujtaba Ali and his readers.

In some ways, Deshe Bideshe is a story of colonial and imperial mobility, which became increasingly restricted with decolonization, the drawing of new geographical borders, and the establishment of new bureaucratic immigration regimes in the 20th century. The memory of lost mobility and cosmopolitan lived-worlds haunts Mujtaba Ali's recreation of his time in Afghanistan. We should remember that Mujtaba Ali wrote and published Deshe Bideshe between 1946 and 1948, a period marked by horrific communal violence in India, in the countdown to eventual Partition. In this context, Syed Mujtaba Ali's looking back at the Afghan moment of possibility between 1927 and 1929, and its loss in unchecked violence, echoes his own restless movements across the postcolonial border between India and East Bengal/East Pakistan/Bangladesh. He would never again be at home in any of these places, haunted by accusations of spying and disloyalty, tormented by ill-health and loneliness. His experience was one that was shared by many South Asians in the aftermath of decolonization – that of being an exile in a strange foreign land which once used to be home.

Mou Banerjee is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments