Symbolic and Imaginary in Nazrul Islam

I

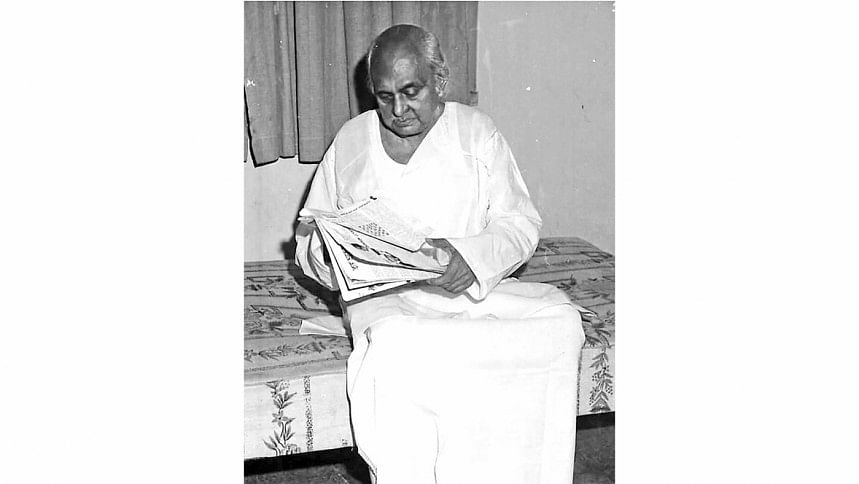

Kazi Nazrul Islam, according to Kazi Abdul Wadud (1895-1970), perhaps the first formidable critic who took him seriously, "was the first writer among Bengali Muslims of the modern era who was able to conquer the hearts of Hindus and Muslims alike of Bengal." Wadud was not wide of the mark when he wrote: "Mir Mosharraf Hossain, Kaikobad, Yakub Ali Chowdhury, Latfur Rahman, Begum Rokaya, Kazi Imdadul Haque are names that will live in the annals of modern Bengali literature, but it was Nazrul who won the esteem and admiration of the entire province." (Wadud 1950: 11-12)

Wadud and, decades after him, the historian Partha Sarathi Gupta (1934-1999) also argued that Nazrul Islam's genius was shaped in the heat of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal. In course of his intervention, 'Modern Bengali Literature,' at the All India Writers Conference, Jaipur, 1945, Wadud noted: "He was perhaps not more than twenty at the time he made his debut in Bengali literature (1919-20). He must have been, therefore, a mere boy at the time of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal. Yet, somehow, he carried about him all the fire and fervour of that movement as he made his debut. His radiant youthfulness and his passion for freedom made him in a short time the darling of Bengal."

What complicated matters for our critic was the fact that, in Nazrul Islam, the fervour and fury of the Swadeshi agitation, which brought real gains for Bengali Hindu leadership, notably the reversal of the partition of Bengal in 1911, and which was widely taken as a snub to the interest of Bengali Muslims, "was combined with an ardent desire to see his community gain in strength and spirit, and anguish on account of the distressed Islam of the years following the Great War of 1914-1918." (Wadud 1950: 11)

Partha Sarathi Gupta's take, just a few years before his premature demise, echoed K.A. Wadud's concerns: "He holds a pre-eminent place in the story of efforts to communicate through music the ideal of a nationalism rising above religious differences." (Gupta 2001 [1996]: 428)

What differences? Some became apparent in course of the Swadeshi agitation against the partition of Bengal. The movement produced a remarkable crop of patriotic songs by many, and music proved one of the most effective techniques of mass contact. "However," Gupta adds, "the appeal of the agitation to Muslims in general was limited. While one cannot deny the involvement of some Muslim leaders and their followers, and the composition of patriotic songs by Muslim writers (like Ismail Husain Shirazi), most of the songs and plays had not shed Hindu imagery and historical allusion to the 'glories' of ancient Indian civilization. The revolutionary secret societies excluded Muslims from membership, even when some young Muslim boys wanted to join them." (Gupta 2001 [1996]: 428)

In the wake of the Swadeshi agitation and the imperial policy of introducing separate electorates, the distance became apparent. As Gupta writes, "we have to concede that henceforth the anti-imperialist forces in Bengal could not, at all critical conjunctures of social and political crisis, avoid thinking in terms of the relative gains and losses that would accrue to each community from any new political development." (Gupta 2001 [1996]: 428)

The annulment of the partition of Bengal (1911) was unpopular with most Bengali Muslims, especially East Bengal Muslims. They were also hurt, even in their imaginary, by the fact of Britain's stand against Turkey, which was allied to Germany, in the Great War of 1914-18. The lesser demographic weightage granted to Bengali Muslims in the Lucknow Pact of 1916 also embittered them. Thus the Bengali Muslim goodwill to make a common cause with the Bengal Congress for a Hindu-Muslim alliance to demand constitutional concessions from the imperial administration was already fraught with fragilities. In these circumstances, when the fragile Hindu-Muslim alliance bore fruit as the Government of India Act, 1919, Nazrul Islam was demobilized because the regiment to which he belonged was disbanded in March 1920.

As is well-known, Nazrul Islam's first literary output began to appear mostly in journals edited by young Muslim intellectuals in Kolkata, the future communist leader Muzaffar Ahmad among them. As is also well-known, his poems and songs made him popular among both Muslims and Hindus, keeping guard with the sentiments of Khilafat and Non-cooperation agitations in which he participated.

Nazrul Islam made common cause with the efforts of C.R. Das (1870-1925) to regroup nationalists after the failure of the agitations by 1922. However, these efforts soon proved ephemeral with the death of Das in 1925. P.S. Gupta notes the determining factors: "Protest movements among different sections of society—workers, the student community, the lower middle class which contained a sizeable number of ex-terrorists—could not be coordinated and given a steady anti-imperialist aim. Among the Hindu bhadralok class there was a recrudescence of the Hindutva sentiments of the swadeshi period, a sentiment which found literary expression in the writings of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay." (Gupta 2001 [1996]: 433)

On the other side of the divide, it is a recognized fact that, despite a notable share of the Bengali Muslims in the making of early Bengali literature, the Muslims of the colonial era failed to take a worthy share in the making of modern Bengali literature. K.A. Wadud holds the political changes of the eighteenth century as well as the Islamicist reform movements of the nineteenth mainly responsible for this misfortune. Without necessarily taking such a myopic view, we can concede that in the first half of the nineteenth century, while the Hindu cooperated with the British, a significant part of the Muslims for the most part remained 'sullenly hostile' and after the uprising of 1857, they faced the wrath of the conquistadores. Neither the Islamicist reform agitation nor the prostrations of Aligarh did much to rescue the Bengali Muslims from their torpor.

K.A. Wadud's remark is apposite: "The Aligarh movement of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan did something towards the uplift, mental as well as mundane, of the Muslims of North-Western India, but left Bengal practically untouched. Thanks to Syed Ameer Ali, a disciple of Sir Syed Ahmad, just a faint ray of modernism touched the minds of the English educated Muslims of Bengal, but it was too faint to be effective." (Wadud 1950: 13).

We are going to determine this while we are still at the aphelion [farthest point from the sun] of our matter for, by the time we reach the perihelion [nearest point from the sun], the heat will be able to make us forget it. Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (Lacan 1966: 242)

That the English educated Muslims of Bengal did not, for the most part, represent the Bengali Muslims did not deter Kazi Abdul Wadud from making generalizations need not blind us from his appreciation of Nazrul Islam's debut as a tour de force (his 'true worth' in manner of saying) in the history of the Bengali Muslims. "Some have not hesitated," Wadud admits, "to describe his writings as ephemeral. This view, however, no longer holds the field. None in the literary world of Bengal would deny today that Nazrul is a memorable poet of twentieth-century Bengal, nay, of India." (Wadud 1950: 12).

II

Talking of the historical importance of Nazrul Islam as one of the factors of the awakening of the masses of Bengal, Wadud is led to enquire about the question of the 'true worth' of Nazrul Islam as a literary figure. His first anxiety relates to the persistence of a dualism (as distinguished from 'syncretism' celebrated by the Orientalists) widely noted in the Bengali poet's theology.

Wadud formulates the problematic as not simply coexistence of Islamic and pagan traits, but of their simultaneous development: "Nazrul Islam has endeared himself to his co-religionist of Bengal by his poems and songs on Islam and Muslims. He is also widely held to be responsible for a new ferment among them. But along with his pieces called Islamic he has penned innumerable lines in eulogy of gods and goddesses of the Hindus over which his coreligionists do not feel comfortable." (Wadud 1950: 123).

Wadud proposes an understanding of this problematic as the fact of cohabitation of the Islamic symbolic with the Hindu Imaginary simultaneously in every Bengali Muslim true to his creed and to his soil. Thus, Kazi Abdul Wadud writes: "The Mussulmans of Bengal sprang, it is undeniable, mostly from the Hindus, i.e., Buddhists and Hindus, of the land. Man's emotional awareness is hardly a fact till he realizes his intimate relationship with fellow man and nature. That emotional awareness again is vitally linked with man's self-assurance of the powers he has been born with (which is another name for Renaissance). So, the Mussalmans of Bengal wishing their own fulfilment must have a deep comprehension of the environment they have been born in and of their heritage from their ancient Hindu forbears—even as Firdausi felt the compelling need of realizing the greatness of his non-Muslim ancestors. The matter may well be likened to the tree's thrusting of roots deep down into the earth to draw nourishment from there." (Wadud 1950: 124-25).

A second problematic that worried Kazi Abdul Wadud concerns a sign of self-confidence, sometimes taken for a wonder. Nazrul once uttered "I bow to no one except to myself", and the utterance, as Wadud takes it, "was no stray outburst but the expression of an abiding feeling in him—it is in fact his dominant feeling." (Wadud 1950: 127-28).

We would suggest this dominance as an outburst of the Symbolic, in the sense in which Jacques Lacan (1901-1981), the psychoanalyst, employs the notion. Lacan's use of the term symbolic endeavours to show how the human subject is inserted into a pre-established order which is itself symbolic in nature, where the symbolic, exemplified by language as the structure per excellence provides prototype of the unconscious.

Wadud pays tribute to this notion of the symbolic when he writes the following: "The popular ways of viewing him as a poet of Rebellion, as a champion of the cause of the have-nots, as a unifying force between Hindus and Muslims are not to be challenged; they are good inasmuch as they endear the poet to us by stimulating in us some creative thoughts peculiar to our age and environment; yet it is too true that his Rebellion, his espousal of the cause of the have-nots, his endeavours to unite Hindus with Mussalmans, all are rooted in his sense of glory of the self and have derived their potency from that consciousness." (Wadud 1950: 128).

REFERENCES

Jacques Lacan, Écrits (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1966).

K.A. Wadud, Creative Bengal (Calcutta: Thacker Spink, 1950).

Partha Sarathi Gupta, Power, Politics and the People: Studies in British Imperialism and Indian Nationalism, ed. Sabyasachi Bhattacharya (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2001).

Salimullah Khan is a Professor at the General Education Department of ULAB.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments