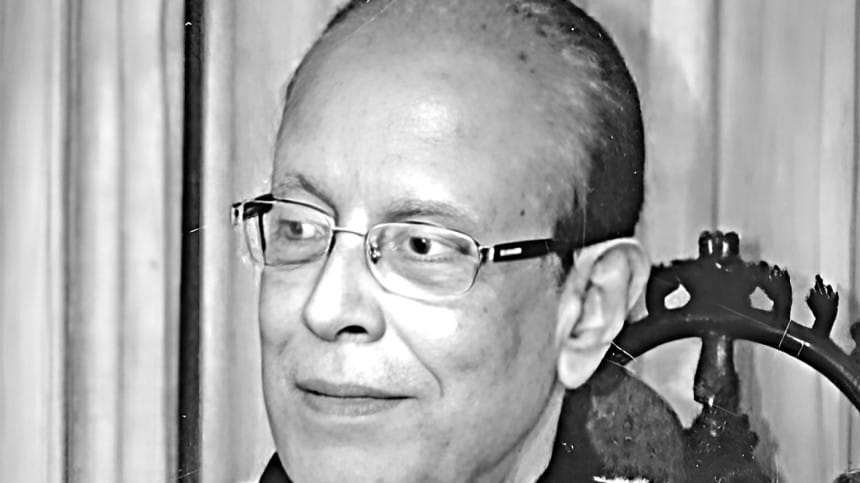

In 1961, the Arts Faculty of the University of Dhaka was still located at the southern end of Dhaka Medical College and Hospital. It was there, under the high-ceilinged rooms with their antique benches that Dr Khan Sarwar Murshid taught the MA English Preliminary students. He would be there only for a few months because, later that year, he would leave for Harvard. Our classes were lecture-based. Teachers spoke, students listened. The only occasion we had for close contact with teachers was during our tutorials when four or five of us met our tutors. I was lucky to have Dr Murshid as one of my tutors. However, much as I strove to write good tutorial essays, the highest mark I ever received from him was a B+. We were too intimidated in those years to talk to our teachers and I never asked him how I could improve my grades.

Dr Murshid was assigned to teach John Donne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. We still teach Donne but Rossetti has grown out of fashion. Perhaps even in the early sixties Rossetti was not important, but Dr Murshid's teaching of Rossetti and Donne was like a breath of fresh air. Theory was quite unknown those days. The study of a writer's biography was quite common. And teachers who had good voices often read texts aloud in class. Both Donne's poetry and Rossetti's came alive in Dr Murshid's voice. I can never forget the charismatic teacher, tall and strikingly handsome, reading English poetry as it should be read. Donne's "A Valediction Forbidding Mourning" and Rossetti's sonnets embedded themselves in my senses. Sadly, he was not there when I was in my final year MA, so I did not get to learn his thoughts on W. B Yeats and T. S. Eliot – on whom he had written, along with Aldous Huxley – for his doctoral dissertation.

New Values set an intelligent critical standard, and tempered its Bengali preoccupations with good articles from overseas, and translations and critical discussions of modern writing from other Islamic countries. For a man in his early twenties all this was considerable achievement.

Dr Murshid had barely known me for a few months. In the ten years since my classes with him, much had happened. How well did he remember the girl in braids in his tutorial class? Yet, in late January 1972, when I visited him, saying that I needed a job, that I was now qualified as having taught for seven years, one and a half of them at Chittagong University, he listened quietly. A few days later, I learned that I had been appointed on an ad hoc basis in the Department of English. If that brave man had not listened sympathetically to me, I would not have been where I am today.

In Memoirs of Dacca University 1947 - 1951, A.G. Stock describes Dr Murshid's bravery during the riots of the 1950's. She comments, "I was full of admiration for Murshid's courage." His readiness to act when action was needed, his courage to do the right thing, was as much a part of him as was his love for books. Dr Murshid's recommending a Punjabi for a post when Bangladesh had fought an army composed largely of Punjabis required great courage – and he had that in plenty.

In a moving tribute to her father, "The Intellectual Journey of Khan Sarwar Murshid," published in the Daily Star on December 8, 2020, Tazeen Murshid sums up his concept of values – and perhaps explains how he could take the step that he did when he recommended me.

At the core of Murshid's world view had already evolved the concept of values. It included ideas of order and moral responsibility, justice and right conduct, truth and beauty as the measure of such an order. He summed these up in his concept of values. To him, values were what made a man, and those values are what held society together.

Tazeen Murshid notes that even before her father began his doctoral studies, "he embarked on his spiritual journey into ancient Indian philosophy in the context of his literary studies." He had thought of an intellectual platform where these values could meet. They would be new values and that was what he called the name of his quarterly journal when he started it in 1949. It was two years after Partition and the creation of Pakistan; Bengalis had not yet lost faith in Pakistan. He was just a young man of 25 when he started New Values. He would continue the journal for 14 years, trying to publish the best of current thought, poetry and fiction.

Professor Stock, in her memoirs, discusses the importance of New Values and how it "set out to focus on the many-sided thought that was stirring in East Pakistan."

New Values set an intelligent critical standard, and tempered its Bengali preoccupations with good articles from overseas, and translations and critical discussions of modern writing from other Islamic countries. For a man in his early twenties all this was considerable achievement, and it bears witness to the liberating mental atmosphere of life in Dacca at the time.

New Values was remarkable for including not just essays, but also stories, poems, translations, and book reviews. Its writers included Bengalis, Indians, West Pakistanis, English men and women. The topics ranged over politics, economics, literature, and philosophy. Syed Waliullah's story, "The Escape," which was first published in PEN Miscellany from Karachi in August 1950, was republished in New Values, 4, in 1952.

Thanks to the publication of New Values for a New Generation (Bangla Academy, 2019), we can appreciate the range of the pieces that appeared in in the journal. Among the 28 selected pieces are writings on the Bengali mind, modern Bengali music and Nazrul Islam, poetry in East Pakistan, essays on Ghalib and Iqbal, on Sarojini Naidu and Yeats. There is also an essay on comparative literature – written by Dr Murshid and Henry Widdowson, then working for the British Council. But there are also essays on politics, economics, religion. A. G. Stock's essay on literature is included as are some of her poems.

Thanks to this publication, today's reader can not only understand the mind of East Bengal during those years, but also the broadness of the vision of the young editor. Today, when Bangladeshi readers and scholars claim all of literature as their own, it is pleasantly surprising to see how just after the creation of Pakistan a young man was reaching out to the world as well as projecting the world of East Bengal and its mind to readers in English wherever they were. As his son, Kumar Murshid, who is co-editor of this volume, says, "New Values, for a crucial period in our history, provided a progressive platform for intellectuals and poets in Bengal and beyond to re-evaluate and redefine their identity and aspiration as citizens of a Muslim state in which the concept of a 'Bengali Muslim' identity was taking shape alongside the shaping of the secular Bengali identity."

In his tribute to Professor Murshid, "The Inspirational Dr. Murshid" (Khan Sarwar Murshid: Sangbardhana Grantha, 2012), Fakrul Alam regrets that the one failing "Of this remarkably learned and intellectually vibrant man" was that "almost nothing by him can be found in print." True, apart from his Introductions to Contemporary Bengali Writing: Pre-Bangladesh Period (UPL,1995), and Contemporary Bengali Writing: Bangladesh Period (UPL, 1996), the essays collected in Kaler Katha (Mowla Brothers, 2001), and the posthumous publication of his doctoral thesis, Indian Elements in the Works of W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot and Aldous Huxley (UPL, 2021), there is nothing. Why didn't Dr Murshid write more? One answer might be that he read too much.

The first mention we have of Dr Murshid in Professor Stock's Memoirs of Dacca University reveals his fondness for reading: "Murshid spent a good deal of time reading at the bungalow. He was interesting to talk to and accommodatingly easy to ignore when either of us was busy." An anecdote provided by Fakrul Alam also suggests Dr Murshid's ability to ignore the world while engrossed in a book. "I had gone to his house to meet his daughter Tazeen Murshid, a good friend, and we talked and talked for almost ninety minutes. All this time I saw him sitting in his study, fully focused on the book that he was reading. When I left Tazeen that day, he was still glued to the book and his desk!"

My brother, Raza Ali, who was also a student of the English Department, did not get to take any of his classes because Dr Murshid was at Harvard for much of my brother's time at the university. However, there was an approachability about Dr Murshid that led to my brother visiting him after he got a good job. Dr. Murshid was disappointed in the choice my brother had made. He explained that money and status were not important, and for him as long as he had his books and record collection he was content. He encouraged my brother to continue with his studies. (A few years later, my brother did that.) Perhaps those who read too much do not have time to write.

However, there was perhaps another reason which no one has quite pointed out. He was a perfectionist. Mizanur Rahman Shelley, in his essay "The Maestro of Moving Times" (Khan Sarwar Murshid), describes how students belonging to a government backed organization had beaten up Professor A. N. M. Mahmud. Dr Murshid was the Secretary General of the Dhaka University Teachers Association (DUTA). The teachers met in the Teachers Club and condemned the incident. Dr Murshid had the responsibility of drafting the press release. Mizanur Rahman waited impatiently for it. He urged Dr Murshid to hurry as the press were waiting. Dr Murshid responded by saying that "these things need to be prepared with great care." Mizanur Rahman blurted out, "Sir, if you were the Editor of a daily it would have come out once in a fortnight." Dr Murshid was not perturbed. He stopped correcting the draft, took off his glasses and looked quietly at Mizanur Rahman for a few minutes. He then went back to correcting what he was writing and only when he was satisfied did he give the statement to Mizanur Rahman.

We do not know why Dr Murshid did not publish his thesis that had been highly recommended by Professor Geoffrey Bullough, the External Examiner. Perhaps by the time Dr Murshid had finished writing his thesis, the business of the world called upon him. And he was not one to shy away from action when needed. Things were not all right. His views were the very opposite of the powers that be. He had played an important role in the centenary celebrations of Tagore. It was a dangerous position to take at a time when singing Tagore songs was banned. Though not directly involved in politics, his advice was often sought. But academics who refuse to toe the line of the party in power are not always appreciated. In "A Tribute to Professor Khan Sarwar Murshid: A Man of Values" (Khan Sarwar Murshid), Dr Rehman Sobhan suggests something of this sort happened after 1971. After a brief stint as Vice Chancellor of Rajshahi University, Dr Murshid was sent to Poland as ambassador. As Dr Rehman Sobhan points out, Poland was "not a country which was likely to bring out his best talents."

Subsequent political events must have disheartened the man who had started out with the hope of a world of possibilities. Perhaps that is why he withdrew from a world so different from the one he and some of his colleagues had envisioned, immersing himself in his books and teaching occasional classes at the university. Perhaps that is why he had also attempted to bring out a collection of pieces from New Values, pieces which were indicative of a time when the Bengali consciousness was rising but divisiveness had not rent the nation. The publisher he approached at the time was not interested.

Fortunately, his son recognized the importance of New Values and was able to convince Shamsuzzaman Khan of Bangla Academy to bring out a selection of pieces from the journal. As Dr Murshid says in his Introduction to New Values for a New Generation, "New Values was much more than a high brow literary journal. It had become the voice of a new generation of youthful intellectuals who fostered a globalized perspective on the key issues facing Bengali Muslims and their new nation Pakistan in the context of an analysis of the experience of other postcolonial developing nations."

The new millennium would have shown Dr Murshid a world very different from the one that Bengalis of his generation had hoped and fought for, in words and actions. He would have felt very much like Yeats, the last romantic, with whom his daughter Tazeen says he identified the most.

Niaz Zaman is a retired academic, writer and translator.

Comments