The Portrayal and Relevance of Women in Kazi Nazrul Islam’s Novels

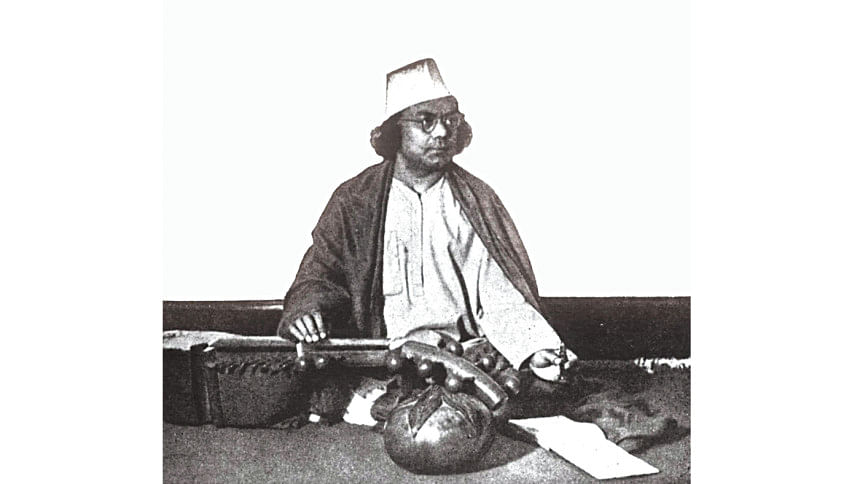

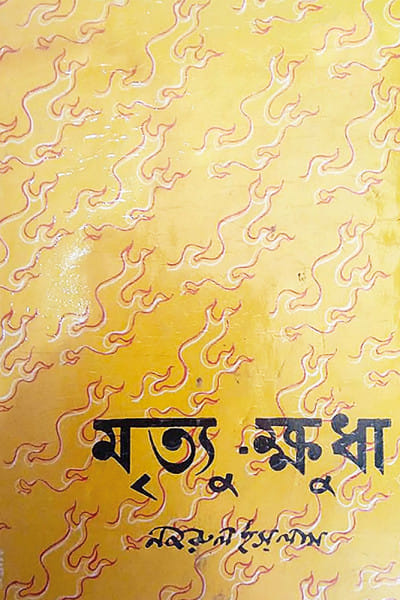

Kazi Nazrul Islam is our National Poet, but, in addition to writing poetry and composing songs, he also wrote fiction. In fact, Nazrul's first publication was not poetry, but the short story "Baundeler Atmakahini" (The Autobiography of a Vagabond), published in Saogat in May 1919. One of his most powerful short stories is "Rakshushi," the personal narrative of a woman who has killed her husband. Nazrul also wrote three novels: Bandhon Hara (Unfettered), Mrityukshudha (Deathly Hunger/ Hunger for Death; translated as Love and Death in Krishnanagar) and Kuhelika (The Enigma; translated as The Revolutionary). While love forms a strong focus in all three novels – all three having a triangular love story – if readers read these novels only for their love story, they will miss out on the social comments that Nazrul makes in them as well as his exploration of a woman's psyche.

Surprisingly, for a man so young – he was only about 21 when Bandhon Hara started being serialized in Moslem Bharat from mid-April 1920 – he was able to enter the recesses of a woman's mind and heart. Though Nazrul's experiences as a soldier inspired him to write Bandhon Hara, this epistolary novel – perhaps the first such novel written in Bangla – also provides details of the lives of Muslim women in the early years of the twentieth century. In addition to the Muslim women, there is also a Brahmo woman in the novel, one of whose functions is to show the contrast between the lives of Muslim women and the freer Brahmo woman.

Bandhon Hara consists of eighteen letters, five of them written by the protagonist Nurul Huda, familiarly known as Nuru. The narrative that emerges through the letters is about Nuru's love for two women – Mahbuba and Sophie – and theirs for him. Though it is not clear whom Nuru is fonder of, a marriage is arranged between him and Mahbuba. However, he is unwilling to barter his freedom for love and escapes the bondage of marriage by enlisting in the army. Mahbuba and Sophie are both married off. Sophie falls seriously ill immediately after her wedding. Mahbuba is married to a rich old man, who dies soon after their marriage, leaving her a widow.

While the letters of Sophie, Mahbuba, Shahoshika, Ma, Rabeya, and Ayesha develop the love story, they also provide vivid details of the purdah world of Muslim women. The letters describe women as victims of a conservative society, social conventions and patriarchal prejudices, but they also reveal that women are individuals with hopes, aspirations, and desires. For example, in her letter to Mahbuba, Rabeya, the wife of Robiul, Nuru's friend, describes how she fell in love with the man who would later become her husband. She stresses that even women, locked up in the inner parts of the home, have feelings and emotions. The only reason that the world does not know is because women are obliged to conceal these feelings.

Mahbuba's letter to Sophie describes how religion and society deprive and subdue women. Religion itself has been perverted and misinterpreted. She laments to her friend that the inner quarter where women reside is claustrophobic. It is a place where even the sun may not enter. She cries, "But. . . we are not criminals. We are entitled to some freedoms, for are we not human beings? Are we not made of flesh and blood, don't we have feelings? Do we not possess a soul?" In her essay "Subah Sadek" (Early Dawn), Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein (1880-1932) exhorted women to proclaim aloud, "Amra manush." We are human beings. In Aborodhbashini (The Secluded Ones), published in 1931, several years after Bandhon Hara, she described the claustrophobic, unhealthy and often fatal conditions of extreme purdah.

By using letters for the characters, Nazrul Islam was able to give his women a voice that they had been denied and that is generally associated with Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein. They reveal the female renaissance that was taking place in the early years of the 20th century. Though it is the Brahmo Shahoshika who is free to teach in a school, there is hope that Khuki, the young daughter of Rabeya and Robiul, will be able to go to school one day.

Mrityukshudha, Kazi Nazrul Islam's second novel, began to be serialized in Saogat from November 1927. Published as a book in 1930, it is similar to his other two novels in having a rebel hero and a triangular love affair. Initially, the focus of the book is on the poverty that Nazrul witnessed in Krishnanagar where he had moved with his family in 1926. The narrative describes the conditions of the household of Gojaler Ma, whose three sons have passed away, leaving behind their widows and their orphaned children, and only one brother to somehow earn a living for all. The daughters-in-law do not have names but are known by their position in the order: Boro Bou, Mejo Bou, Shejo Bou.

In chapter fifteen Nazrul introduces the Bolshevik Ansar who speaks about the rights and freedom of coolies, sweepers, carters etc. However, Ansar is also a frustrated lover, whose beloved, Ruby, was forced to marry someone else. Through Ruby, Nazrul criticizes the strictures that society places upon love. In Bandhon Hara, Kazi Nazrul Islam had described women's desires through Rabeya's letter to Mahbuba but also noted how they were obliged to restrain their feelings. In Mrityukshudha, however, he shows a woman who defies all religious and societal proprieties when she learns that the man she loves is dying. In a passage, perhaps unequalled in the Bangla novels of the 1930's, Ruby describes her relationship to Ansar in a letter to Latifa, her cousin. "He could not get enough of me. I started to cry, not for myself – for him. This overwhelming hunger was not just my death – it was also his death. He was seriously ill. Did he have the strength to devour me and live? I knew that the great enemy of his disease was giving in to desire. Otherwise, that self-control of Ansar's, harsher than the discipline of an ascetic, why did it succumb to this mrityukshudha, this death-wish?"

While the story of Ansar and Ruby juxtaposes the love element with the revolutionary theme, the story of Mejo Bou, who also falls in love with Ansar, shows the plight of an uneducated, impoverished Muslim woman and reveals how she attempts to rise above her lot in life. The arrival of two Christian missionaries with medicine for the ailing Shejo Bou, the widow of her younger brother-in-law, acts as a catalyst to change her life. The missionaries offer education and freedom.

Mejo Bou takes the Christian name Helen after being baptized. Nazrul seems to suggest that conservative Muslim society does not recognize a woman's individual identity. It is only by converting that Mejo Bou becomes an individual. Speaking to a group of other Christian women at Barishal where she had been sent, she explains, that she did not come to become a mem saheb, but a human being. "We are deprived of light and air. That is why I escaped like a caged bird which bites through the ribs of its cage. I will not say I have not benefited. Whatever I have learned here will enable me to stand on my feet, support myself."

Kuhelika, which started being serialized in 1927 and was published as a book in 1931, was advertised as a novel about a revolutionary. The late Professor Kabir Chowdhury, who first translated the novel into English – retaining the Bangla title for the translation – also stressed the story of the revolutionary: "It is among the pioneering political novels in Bengali and the first one to have a Bengali [Muslim] youth as its revolutionary hero."

However, the novel opens with a group of young men in a boarding house discussing women. Are women enigmas? Muses? Do they mould themselves into the expectations the world has of them? The novels by Tagore and Sarat Chandra were very much in Nazrul's mind when he has Jahangir ask Haroon, his friend, "Woman has inspired so many novels such as Chokher Bali, Ghare Baire, Grihadaha and Charitraheen. How many have you read, poet?"

The beauty of women and the rapacity of men are stressed by Haroon who believes that without these acts of violence literature would not have been possible: "Would the Ramayana exist if Sita had not been abducted by Ravana? We have been blessed with the great gift of the Mahabharata only because the Kauravas dragged Draupadi into the court by her hair." This violence is also to be seen in Kuhelika when Jahangir rapes Tahmina, Haroon's sister, one night.

Nazrul depicts the complexity of sexual attraction and repulsion. Jahangir is perhaps the first man Tahmina – or Bhuni is she is often called – has seen and she is attracted to him. She sees Jahangir bathing – a common enough occurrence in a village – and is mesmerized. After Jahangir has finished bathing, her eyes fall on him again. "Standing there he looked like a marble statue carved by some Greek sculptor. Primitive man on seeing the first sunrise must have looked on the red and gold sky with a similar astonishment." Jahangir's mother is anxious to get Jahangir married and, when she learns that Tahmina's mad mother has pledged her daughter to Jahangir, visits Haroon's family with a formal proposal. Everything seems perfect. Then one night, while Jahangir is sitting alone, Tahmina looks at him from the door of the house for a long time. She finally tries to close the door but there is a noise. Jahangir looks up and sees her. They talk and, at one point, Jahangir laughs loudly at something that she has said. She again tries to shut the door of her room, but accidentally hurts herself. Jahangir attempts to soothe her bruised finger by kissing it.

Frightened of her own feelings and of what Jahangir is doing, she asks him to release her. However, she is helpless before the sexually aroused young man who succeeds in overpowering her. The godly prince has turned into a bloodthirsty beast.

Leaving Tahmina behind, Jahangir gets deeply involved in revolutionary activities against the British. He meets other revolutionaries including a female revolutionary and her daughter Champa. When the older woman is killed while attempting to carry out a terrorist act, Jahangir is given the task of delivering weapons. He is accompanied by Champa. As they journey by train, he expresses his feelings for Champa. However, when he had first seen Champa, he had thought immediately of Tahmina and that, like her, Champa too was an enchantress, someone who beguiled men and led them astray.

Unlike Tahmina, Champa has the strength to resist Jahangir. Champa and Jahangir cannot carry out their mission. Jahangir is captured and sentenced to life imprisonment on the dreaded Andaman Islands. As he is led away, he tells his mother that she should give most of his wealth to Champa to feed hungry mothers and their children. One-fourth of his property should be given to Tahmina, the woman he has wronged. As he is taken away, Jahangir repeats the words of Haroon, "Woman is an enigma." Tahmina responds by murmuring "You are really cruel."

In his discussion of the novel, the late Professor Kabir Chowdhury elides the circumstances of Jahangir's birth, his rape of Tahmina and his attempted seduction of Champa. He thus ignores the psychological aspects of the novel. In her Asiatic review of the translation, Nandini Bhattacharya objects to the translators' describing the sexual encounter between Jahangir and Tahmina as rape. She stresses that it is a "consensual consummation of desire and not rape."

Nandini Bhattacharya admires this last scene, stressing that it is "a celebratory and symbolic moment even in its tragic dimensions. There is a Muslim man, a Hindu woman and both have crossed barriers and prejudices of jaat (community), dharma, (religion) and linga (gender) in sacrificing their lives for the nation." She ignores the complexities of Jahangir's character and actions as she ignores the complexity of Tahmina's relationship with him.

Kuhelika deserves a much closer reading than any reader or scholar has done so far. In fact, no Nazrul critic seems to have explored the psychological dimensions of the novel – perhaps because it is difficult to justify rape or associate it with a hero. However, it is only a psychological reading of the novel that can explain the duality in human beings, that one can be a revolutionary and also a rapist.

While Nazrul's novels and short fiction deserve to be read for the perspective they provide of the times, they are also relevant today. The problems of Nazrul's fictional women a hundred years ago have not been solved. How free are women today? And not just in Bangladesh or Pakistan or Iran? Issues of identity, rape, consensual sex are still very contemporary.

Niaz Zaman, Professor and Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh, is Advisor, Kazi Nazrul Islam and Abbasuddin Ahmed Research and Study Centre, Independent University, Bangladesh.

All three of Kazi Nazrul Islam's novels have been translated into English and published by Nymphea Publication. In 1994, the late Professor Kabir Chowdhury translated Kuhelika, retaining the original Bangla title.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments