In 1825, Charles Dowes, the then Magistrate of Dhaka, initiated the clearing of the Ramna jungle using prison labour. He enclosed an oval-shaped area with wooden railings and introduced horse racing competitions. From that time, the white colonial officials and residents of Dhaka found a source of recreation at the racecourse.

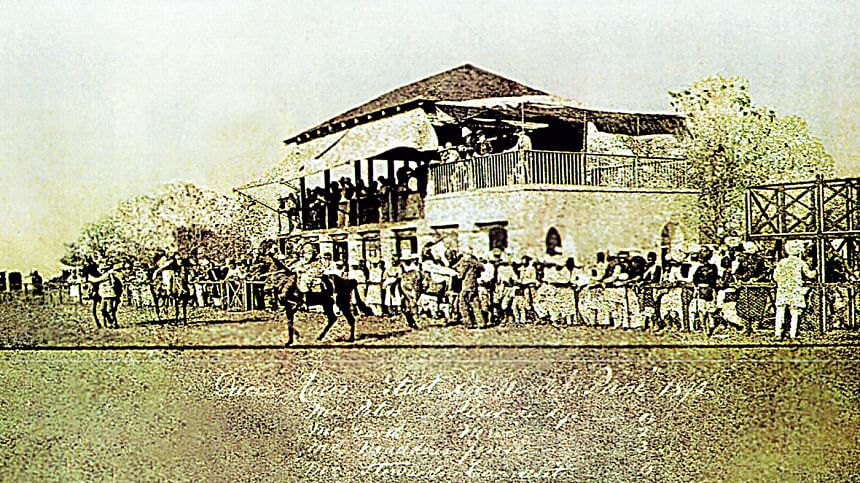

Horse racing became particularly popular as a significant form of entertainment for Dhaka residents during the time of Khwaja Alimullah, Nawab Abdul Ghani, and Nawab Ahsanullah. Khwaja Alimullah organised an annual horse racing competition every January, evidence of which is found in a painting ( Image 1) by an unknown artist from 1845.

The painting depicts Khwaja Alimullah and his son, Nawab Abdul Ghani, dressed in Western attire and hats, along with other notable figures such as Cooper, Captain Hanshon, Hume, Lusani, Husni, Sarkis, Baker, Robin Hood, and James Wise. This rare artwork is currently in the possession of Khwaja Mohammed Halim, a relative of Nawab Abdul Ghani.

Horse Race Holiday

Following in his father's footsteps, Abdul Ghani began hosting horse races in 1848. His first horse, named Sir Henry, was a light brown Arabian stallion. Abdul Ghani bred high-quality foreign horses for racing, which was his favourite pastime and one he pursued with significant financial investment.

The widespread impact of gambling associated with horse racing on the general public is evident from a report published in Dhaka Prakash in 1891. It stated:

"During the horse racing event, all offices and courts in Dhaka were closed once again. On Saturday, operations were completely halted, and on Tuesday and Thursday, they were open only nominally for a brief period, with no work being done. Residents of distant towns, who travelled great distances and incurred substantial expenses to attend court for their cases, found the courts suddenly closed and returned home in frustration, cursing the government.

If instead of closing the courts unpredictably, the government announced a 'Horse Race Holiday' in advance, much inconvenience and harm to the public could have been avoided."

The 'Dhaka Races' in Civilian Memoirs and Nawab Diaries

The memoir Leaves from a Diary in Lower Bengal by British civilian Arthur Lloyd Clay provides significant insights into horse racing in Dhaka. Writing about events in 1865, Clay noted:

"The Dacca Races were now on,—an annual event of some importance on the Turf in Eastern Bengal, liberally supported by Guni Mya and his son Ahsanulla, and other sporting residents, European and native, amongst whom our lively Collector figured conspicuously. A good deal of money was given in prizes, and one or two owners kept European jockeys."

In another entry from 1866, he recorded, "The Dacca Races followed in December," indicating that horse racing had become an established annual event by that time. The Ramna-based races gained fame as the "Dhaka Races."

References to the "Dhaka Races" are also found in Anupam Hayat's book Nawab Poribarer Diaryte Dhakar Shomaj o Shongskriti (Society and Culture of Dhaka in the Nawab Family Diaries). A diary entry dated 5 January 1904 mentions:

"Today, Nawab Bahadur, Mr. Garth, and others have arrived in Dhaka for the inauguration of the 'Dhaka Races.'"

On that day, Nawab Sir Khwaja Salimullah returned to Dhaka from Kolkata, accompanied by D.L. Garth, the manager of the Nawab Estate. Garth tragically passed away in June 1904 during the races due to a fall. He was so well-regarded that his personal belongings were later auctioned at the racecourse by Kolkata's Mackenzie & Lyall Company. A lane in Dhaka's Kumartuli area is named after him.

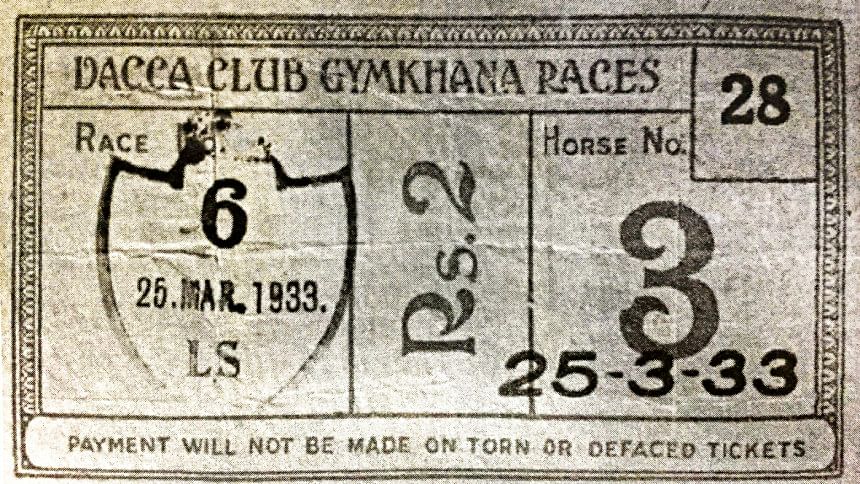

The racecourse was marked as "Race Course" on an 1859 map of Dhaka. However, 19th-century photographs identify it as the Gymkhana Ground or Gymkhana Pavilion. Researcher Walker Khan's book Dhaka Club Chronicles offers further clarification. On page 64, he writes: "On its inception, the Dhaka Club Limited at Ramna took over the management of the Old Gymkhana Club and its lucrative weekly racing events, reorganising and naming it as Dhaka Club Gymkhana Races (DCGR)."

The Diary of the Nawab Family (1793–1903) records that in 1851, Khwaja Abdul Ghani donated land in the Ramna area to the Dhaka Club. However, the club was officially registered much later, in 1911.

Corporate Social Responsibility by Dhaka Club Gymkhana Races

The primary source of income for the Dhaka Club Gymkhana Races was horse racing. The revenue generated was used not only for the club's development but also for corporate social responsibility initiatives. Donations were made to various hospitals and charitable institutions in the city.

Evidence of these contributions can be found in the Triennial Report on the Working of Hospitals and Dispensaries in the Presidency of Bengal for the Years 1938, 1939, and 1940. The 1940 report lists the Dhaka Club Gymkhana Races in fifth and ninth place among major philanthropic contributors. That year, it donated ₹2,500 to Dhaka Mitford Hospital and ₹1,500 to the Narayanganj Dispensary.

Despite these expenditures, the profits from the races continued to rise. This led members to demand reduced subscription fees and subsidies in other areas.

'Queenie' Case

In the fourth chapter of J. C. Galstaun's Racing Reminiscences, an extraordinary incident related to the Dhaka Race is described. It took place in January 1896. The Armenian Galstaun's horsemanship was unparalleled. He was the best jockey in Kolkata at the time and also the largest horse owner of the era.

His stable was in England and was legendary. His bay-colored pony named Queenie won three consecutive races in Dhaka over three days. On the first day, in the Cooch Behar Cup, he earned 1000 rupees; on the second day, he earned 1000 rupees from Nawab Ahsanullah, and on the third day, in the Merchant's Cup, he earned 750 rupees. During this time, the jockey for the horse was a man named Stephen. One common condition for these races was that "the participating horses must be the true property of residents of Dhaka and certain neighboring districts." However, Stephen forgot to inform Galstaun about this condition. Instead, he only sent a written copy of the race prospectus to Galstaun, and after a series of correspondence regarding betting with Galstaun, Stephen died.

Stephen's death led to a major issue. Galstaun was accused of winning the races by violating the condition and using Stephen unethically. The Stewards of the races did not believe Galstaun's response that he was unaware of the betting-related condition. Additionally, Galstaun failed to provide the written prospectus sent by Stephen as evidence. Galstaun couldn't find it at the time. Consequently, on December 10, 1896, an announcement was posted in the Racing Calendar:

"The Stewards confirm the decision of the Dacca Stewards disqualifying the pony 'Queenie' for the Cooch Behar Cup, the Nawab of Ashanolla's Purse, and the Merchant's Cup, at the Dacca races, in January, 1896, and awarding the two first mentioned races to 'Nelly II', and the last mentioned race to 'Free Lance'. Under rule 81 of the rules of racing, Mr. J. C. Galstaun is warned off the Calcutta course and other places where the Calcutta rules are in force. Under rule 82, the pony 'Queenie' is perpetually disqualified for all races."

Feeling aggrieved, Galstaun sought the intervention of the High Court and obtained an injunction to suspend the Stewards' decision. Over three years later, on February 28, 1900, the issue was resolved, and an announcement was made in the Racing Calendar: "The notice in connection with the 'Queenie' case, which appeared in the racing calendar, No. 43, of 10th December 1896, is now withdrawn."

In a cruel twist of fate, in 1908, Galstaun discovered the written copy of the Dhaka race prospectus sent by Stephen among some insurance-related documents. On July 13, he wrote a two-page letter to the highest authority at the Calcutta Turf Club (C.T.C.), C.T.C. The response from the Secretary of C.T.C. on July 15 was as follows:

J. C. Galstaun Esq.,

1, Sukeas Lane,

Calcutta

Dear Sir,

With reference to your letter of the 13th instant with accompanying copy of the prospectus in writing of Dacca races, I am directed by my Stewards to say that they regret they cannot re-open the question of your disqualification twelve years ago but your letter has been noted and filed with the other papers.

Yours,

J.Hutchison

Secy., C.T.C.

Galstaun's case became a significant part of the history of the racing industry, not just for the Dhaka Club Gymkhana race but as a case study in racing history.

Insights from the 1945 Official Race Book of the 'Dhaka Club Gymkhana Races'

A review of the 1945 Official Race Book of the 'Dhaka Club Gymkhana Races' reveals several noteworthy details. The cover states: Monsoon Meetings, Saturday 30th June 1945 Commencement at 2.30 PM Second Day. The booklet was priced at four annas.

On the first page, the names of the stewards and officials are listed. Another page, titled "Notice," systematically lists the dates for the Monsoon Meetings 1945: July 7th, 14th, 21st, 28th, and August 4th. Notably, all of these dates fall on Saturdays. The time for the first race is mentioned as 2:30 PM. Under the heading "The 'Cannaught' Stakes," the prize structure for the first race is as follows:

First Prize: 90 rupees

Second Prize: 55 rupees

Third Prize: 40 rupees

Fourth Prize: 15 rupees

The booklet also specifies the type of horse eligible for the race, with a distance of four and a half furlongs. Additionally, the names of 11 jockeys, brief descriptions of their attire, as well as the names, weights, and ages of the horses, are included.

The book details eight races, with descriptions provided until 6:00 PM. Another page outlines 14 rules regarding the races. The final page provides information about the band program scheduled to take place at the racecourse in the evening.

Horse Racing in the Memoirs of Writers from East Bengal

Horse racing was immensely popular among the people of Dhaka. This chemistry of horse racing is vividly portrayed in the memoirs and autobiographies of contemporary poets, writers, and authors.

Buddhadev Bose, one of the early students of Dhaka University, captured the scene of the 1930s' Ramna and horse racing in his autobiography "Amar Jowban" (My Youth). He painted a picture of the era:

"The northern part is home to the government's elite, the middle has the British-style horse racing field, and the inaccessible Dhaka Club for Dhaka's citizens, where affluent, ball-dancing white rulers and the mill owners of Narayanganj gather for evening social events; and there is a Kali temple with a high spire surrounded by a garden, where many prominent figures come to offer their tributes. ... But the southern part was entirely under the university's jurisdiction, where crowds could be seen, not only students and professors, but also during the winter and monsoon Saturday afternoons, when gamblers and prostitutes filled horse-drawn carts, continuously heading towards the racecourse—disturbing the peaceful Ramna and throwing harsh dust into the faces of those returning from college.

The intricate portrayal of the horse racing culture of that time has also been detailed by the writer and editor, Mizanur Rahman, in his book "Dhaka Purana" (Old Dhaka). He writes, "Whether as gambling or entertainment, horse racing was the weekly public festivity for the citizens of Dhaka. The businessmen, indigenous Dhaka residents, and some hardcore horse-racing enthusiasts from Kolkata, along with white rulers and merchant communities, would rush to the Ramna racecourse on Saturdays. ...I also went, not to play, but to watch. ...From distant areas like Savar, Tongi, and Mirpur, crowds of gamblers would pour in. They were called punters. Even before the race began, one could see these hardcore punters at the stables, gathering information about the horses for the day's race from the caretakers, and collecting tips from the jockeys."

Challenges of Horse Racing

In 1943, a question arose in the Bengal Legislative Assembly regarding whether any official from the Dhaka Collectorate or the Dhaka Divisional Commissioner's office was assigned part-time responsibilities at the Dhaka Gymkhana Races. In response, Khwaja Nazimuddin, who was in charge of the Home Ministry, stated that specific government officials had been permitted to work at the Dhaka Gymkhana Races based on recommendations from local authorities. He further clarified that if local officials were satisfied with their work and there was no disruption to their primary duties, he would not propose withdrawing them from this assignment.

The topic of horse racing was debated again during the Second Session of the East Pakistan Provincial Assembly in 1963. Questions were posed to the minister about whether any measures had been taken in the past to ban horse racing in Dhaka, why it was resumed, and whether the government had any plans to ban horse racing in the future.

An analysis of the responses revealed that horse racing was conducted under the Bengal Public Gambling Act of 1867. The Act had been amended once, making betting on horse racing a punishable offence. As a result, horse racing was halted from 2 June 1948 to 25 December 1954. However, a subsequent amendment to the Act on 26 December 1954 legalised horse racing again, allowing betting to resume.

The Assembly discussions also revealed that the government earned an annual revenue of 1.2 million rupees from horse racing, and 644 individuals were employed in this sector to sustain their livelihoods.

'Dacca Races Suspended'

In 1967, the Illustrated Weekly of Pakistan published a news article titled "Dacca Races Suspended." A review of the article reveals that the authorities responsible for Dhaka races were actively addressing malpractice in horse racing. Unregistered bookies were not paying taxes to the government, while the authorities operating the races had to pay a 20% tax to the Gymkhana. Measures were taken to discourage the presence of unregistered bookies at the Racecourse ground.

At that time, Mr. Mapara served as the secretary of the Dhaka Race Club. Efforts by the stewards to run the popular Sunday races in a transparent and successful manner continued. Stewards, respected members of the racing industry, oversaw all aspects of betting during races to ensure that all parties adhered to rules and guidelines. They were often compared to law enforcement at the racecourse.

To improve the environment of horse racing and ensure long-term benefits for bettors, measures were introduced, such as simplifying ticket purchases and designating specific areas for paying betting money. Seating arrangements for third-class spectators were merged with the second-class section. Additionally, the entry fee was increased from 18 paisa to 50 paisa.

Horse racing was a form of leisure for the British officials but often brought misfortune to the impoverished residents of Dhaka. This led to a mosque-based social movement against horse racing and gambling. The Chawkbazar Shahi Mosque became a centre for this movement, led by renowned scholar Mufti Deen Mohammad. Through his Tafsir sessions and sermons, he sought to educate the general public about the harmful effects of horse racing.

As a result, after independence, the government enacted laws banning horse racing, gambling, and alcohol consumption. The Ramna Racecourse was renamed Suhrawardy Udyan, marking the end of Dhaka's beloved Ramna horse races.

Hossain Muhammed Zaki is a Researcher. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Comments