The inspiration for decolonization, as a philosophical term, writes Achille Mbembe, was the 'active will to community' which can be translated as something like 'to stand up on one's own and create a heritage'. The impetus for decolonization in theatre, as it moved from re-instituting indigenous traditions in place of colonial modernity, to retrieving indigenous systems through 'provincializing Europe' as Dipesh Chakrabarty aptly defines, came from different quarters. The Cold War context provided a range of influences, from western European and north American theatre experiments to socialist realisms and socialist internationalism, as well as the inter-cultural practices emerging from Asian-African alliances. The modern Indian theatre drew on these multiple modernities. The outcome was a significant shift away not only from traditional forms of folk theatre and classical Sanskrit drama, but also from the modern colonial theatre in terms of canon formation, actor training, circulation of texts and performances, reception, patronage, and criticism. Institutionally, as part of the 'will to community', a new cultural bureaucracy, often functioning closely with the administrative one, sustained this shift from the local to the national level.

Utpal Dutt differentiated between fact and truth by focusing on their connection with social conflict and argued that fact remains mere bourgeois truth when abstracted from the context of continuous social conflict between the haves and the have-nots and conversely that fact can become a revolutionary truth when it intertwines the realities of conflict, and sides unerringly with the have-nots.

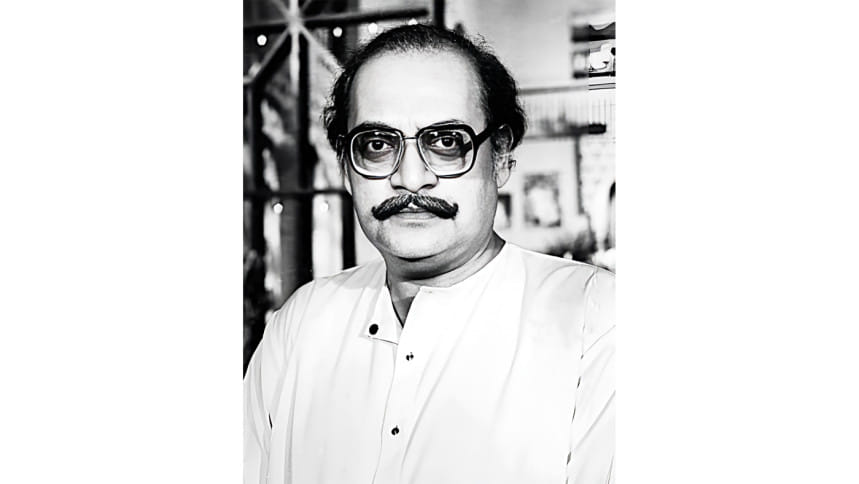

Utpal Dutt (1929-1993) embodied this shift. With the exception of direct involvement in cultural bureaucracy, he straddled the process of decolonization, forging a political theatre of the postcolonial contemporary for modern India. When he emerged as a promising theatre-maker and performer in the city of Calcutta in late 1940s, the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA henceforth), as part of the communist movement in India, had already established itself as a formidable force in cultural politics and the idea of progressive political theatre had started to gain ground. Before his inevitable shift towards IPTA in 1950-51, Dutt was a member of British thespian Geoffrey Kendal's touring Shakespeareana International which, performed Shakespeare's plays in metropolises and mofussil towns across India. Theatre critic Samik Bandyopadhyay notes that the democratic nature of this travelling theatre troupe was crucial in shaping Dutt as an artist. After touring with Kendal, Dutt started his own English theatre group in Calcutta, The Amateur Shakespeareans, and won critical acclaim for modernised productions of Romeo and Juliet (1948) and Julius Caesar (1949).

Dutt's acute sense of the need to engage with the process of decolonization was the reason behind his abandonment of English theatre even after such bravura productions. English theatre in Calcutta was a decidedly elite practice and he turned away from it to begin his stint with IPTA, joining the central Calcutta squad of IPTA as a director and actor and performing in different productions like Tagore's Bisarjan (performed in 1952) and Ritwik Ghatak's Dalil (1951) as well as in various street-corner plays like Bhoter Bhet (1951).

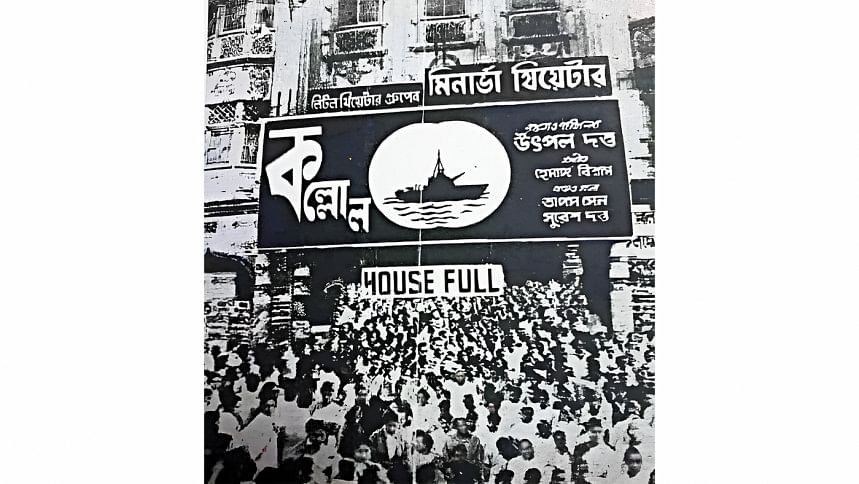

The experience of making theatre with IPTA while engaging with communist politics and Marxist philosophy, though short-lived, became foundational in Dutt's subsequent journey as a political theatre artist. He created his 'Little Theatre Group' (LTG) and, in 1953 leased the Minerva theatre in Calcutta as its permanent home. LTG began with classic Tagore plays, translations of Shakespeare and Russian theatre, and social farces by the nineteenth-century playwright Michael Madhusudan Dutt. Their production of Macbeth (1954) became particularly successful and received invitations for performances even in remote villages, smaller towns and working-class areas. LTG finally found its feet on the Bengali stage with Dutt's Angaar (1959), a play about the lives of coal miners that culminates in a mining disaster and references a recent catastrophe in the Baradhemo coal mine. Angaar became hugely popular not only for its intensely political theme but also because of the sophisticated scenography, sound and lighting design employed. The climax of Angaar, an exemplary feat of stagecraft depicting the despair of seven miners trapped underground waiting to be drowned, is described by Bharucha as an 'epiphany of grief' in which the spectacle of a calamity becomes a source of entertainment and is applauded. Dutt, in his later assessment of his own work, was critical of Angaar because it could not represent the truth of miners' resistance, but was limited to displaying the facts of their huge exploitation.

This tension between truth and fact shaped Dutt's vision of political theatre, which he called revolutionary theatre. He differentiated between fact and truth by focusing on their connection with social conflict and argued that fact remains mere bourgeois truth when abstracted from the context of continuous social conflict between the haves and the have-nots and conversely that fact can become a revolutionary truth when it intertwines the realities of conflict, and sides unerringly with the have-nots. His aim was to represent revolutionary truth because, in his view, presenting only impartial facts risked reifying bourgeois power, and he wanted his theatre to be an agent of change, and thus a factor in the revolution. This meant recounting as many instances of such change as possible, especially historical moments when exploitative regimes are challenged by the poor, the colonized and the 'native'. He aspired to portray the full complexity of power relations at intersecting points in the context of social conflict. This is the reason Dutt so often revisits histories of anti-colonial revolts against the British in India, revolts against other imperial powers in other geo-political contexts, and rebellions against experiences of domination. His stint in the Bengali folk theatre form Jatra, from 1971 to 1988, bears the same marks of revolutionary intent in highlighting historical moments of resistance against colonial/authoritarian regimes.

'One of the ironies of political theatre', observes Rustom Bharucha, 'is that it thrives during the worst periods of repression'. Discussions of political theatre, consequently, need to be continually informed by understanding of the nature of repression and period-specific details of each socio-political situation. In order to make sense of the cultural critique offered by political theatre, the critic has to engage with the defining characteristics of the postcolonial contemporary. This need becomes even more acute in the case of an artist like Dutt because he explicitly identified his project as a revolutionary theatre, that 'addresses these working masses and must adjust its pitch, tone and volume accordingly' in order to agitate for revolutionary social transformation. That his revolutionary theatre was dismissed by a large number of critics as communist propaganda did not dishearten Dutt, but rather he wore the term 'propagandist' as a badge of honour and declared 'to hell with the so-called critics who find our plays naive, melodramatic and loud'.

The recent revivals of his plays from 2018 to 2023 by various theatre groups, including People's Little Theatre that Dutt had created in 1971 after LTG dissolved, invite us to revisit the phase of interconnected histories from a different angle because the impetus to return to Dutt's plays adds another thread to the interconnected histories. This new thread intertwines twenty-first century experiences of the rise of the right-wing, the global south gig-economy, and the coming of a new generation of postcolonial intellectuals. Taken together these threads compel contemporary theatre-makers to bring Dutt's work back to the stage.

Let me list some of these revivals, with the caveat that this list is not exhaustive. I have already mentioned the revival of Titu Mir. Along with Titu Mir came Ghum Nei (1959), a play on the significance of the workers' union, which is now regularly performed by the theatre group Iccheymoto to warm receptions and has received awards for its sets, sound and performance. Sourav Palodhi, the director of the 2023 revival, has argued that this play has contemporary resonance because it underlines the importance of the workers' collective voice in sustaining the secular ethos of Indian democracy (Palodhi 2023). Similarly, Barricade (1972), which comments on the rise of authoritarianism against the backdrop of the rise of Nazism in Germany, was revived by the theatre group Chakdaha Natyajan in January 2022 to comment on the contemporary crises of religious fundamentalism and political violence in India. Another Dutt play Ekla Chalo Re (1989) which re-tells the history of Partition and the subsequent religious riots through the historical moment of Gandhi's assassination in 1948, was successfully revived by the group Swapna Sandhani in 2019.

Finally, Utpal Dutt's legacy remains dependent on and is shaped by these new interpretations of his theatre. His work created a reservoir of memory and his plays and his approach to theatre-making, provide a constant reminder of the importance of history in fashioning the present. The future, however, is being shaped here and now by a new generation of directors, actors and dramaturgs who are making Dutt relevant again, and interpreting his work in ways that facilitate better understanding of the conceptual and material spaces the new postcolonial generation occupies. The process of decolonization in the political theatre of Utpal Dutt, thus remains a vital part of an ongoing movement where every act of thinking and performing is revising, recreating, reinterpreting history. Instead of romanticizing the past, this movement is taking shape as a critical multi-dimensional re-looking at the past, as a working method for making sense of collective political and artistic struggles.

Mallarika Sinha Roy is an Assistant Professor at the Centre for Women's Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

Comments