Vangiya Sahitya Parishat, the first Bengal Academy of Literature

'Academy', as many of us know, is a word that comes from the French word 'academie', evolving from Latin 'academia'—the ultimate ancestor of both being Greek 'akademeia'. Originally, it was a place name, referring to a grove where Plato (428/427 or 424/423 to 348 BCE) established a school. Many of us are aware that Aristotle (384-322 BCE) took his lessons there as the master's arch disciple. The proper name of the original later changed into a common noun, meaning an educational institution in general. However, it later came to mean, in addition, a special kind of institution—a 'cultural' one—for maintaining or improving the standards of a nation's language, literature, or arts and sciences in general.

Paradoxically, it was an English civilian and linguist, John William Beames (1837-1902), who first proposed the idea of an 'Academy of Literature for Bengal' in a pamphlet (1872).

We have two official 'academies' of Bangla language and literature today, along with several others, both official and non-official. By the term 'official', we mean that they are sponsored and supported by the governments of their respective lands. The Indian academies of literature, visual arts, and performing arts were established in the early fifties of the last century. As for Bangla language and literature, the first official academy is the Bangla Academy of Bangladesh, founded in the then East Pakistan in 1955, partly to pacify the restive Bengali populace of East Bengal, which was fighting for the official recognition of their language. Some of its members had already sacrificed their lives for this cause, turning the battle for language into a broader political struggle by then. Therefore, the establishment of the Bangla Academy of Dhaka can be seen as a gesture of appeasement, which, however, grew and flourished beyond the intentions of its creators. We will not delve into comparisons among these disparate institutions, but since Vangiya Sahitya Parishat was (and is) also referred to as 'The Bengal Academy of Literature', we deemed it appropriate to mention other existing academies.

But our Sahitya Parishat was not established through any government initiative. The British Government, somewhat interested in establishing schools and colleges, showed no inclination to have an academy of Bengali literature. Great Britain did not have such an academy either, so it was obvious that the thought would not occur to it. We do not know if the multiplicity of languages and literatures of India was also a deterring factor. Therefore, the proposal for an academy in Bengali literature was privately made, later planned, and finally realized as a non-government organization.

Paradoxically, it was an English civilian and linguist, John William Beames (1837-1902), who first proposed the idea of an 'Academy of Literature for Bengal' in a pamphlet (1872). In it, he explicitly stated that Bengali literature was far ahead of those of other languages in India and therefore deserved an academy of its own. What would such an academy do? Beames proposed that it should standardize the language and improve it by purging both bombastic Sanskrit words and rustic Bengali words. A new dictionary containing such 'chaste' yet simple words would then guide authors on how to write in the language. A Bengali version of this pamphlet was published in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838-1894)'s Bangadarshan (Jyaishtha, 1278) under the title 'Bangiya Sahitya Samaj', just before the original was publicly circulated. Bankim Chandra added a note at the end, complimenting Beames on his erudition, his love for the Bengali language and literature, and the elaborate scheme proposed. He hoped that the intellectual elite of Bengal would give it the attention it deserved and would soon start acting upon it.

However, contrary to Bankim's wish, no quick action followed after the pamphlet was circulated. Bankim Chandra's recommendation seemed to have fallen on deaf ears. He himself was not in a position to take the initiative, as he was stationed outside Calcutta at the time. Nor did anyone else come forward. It took about twenty-one years for Beames's dream to come true. The Bharati, the house-journal of the Tagores, mentioned in 1893 that a feeble and eventually unsuccessful attempt was made about ten or twelve years after the proposal, but it does not elaborate on the reasons or the nature of the failure.

The Academy of Bengali Literature (this was the name at first) finally emerged on 23 July, 1893 (8 Shravana, 1300 BE), at Shobhabazar Rajbati, at the precincts of the 'rajas' of Shobhabazar. The major sponsors were Raja Binaykrishna Deb (1866-1912), a historian of early Calcutta), Shri Hirendrranath Dutta (1860-1942), an advocate, essayist (and, more famously, father of the poet Sudhindranath Dutta, 1901-1960), and the poet and critic Kshetrapal Chakraborty. Binaykrishna had established a 'Sahitya Sabha' or literary society at his residence earlier, but it had the nature of a library only, which held occasional discussions on literature. It was one Englishman again, a civilian named Mr. L. Leotard, reportedly the 'brain' behind the plan, who encouraged Binaykrishna to move beyond a 'sahitya sabha' and proceed towards establishing an 'academy'. He loved Bengali language and literature, and in the eighth session of the Academy, on 10 September, 1893, he pointed out briefly what ought to be its major objectives: "…our object was study: the study of Bangali literature and the publication of the results of that study, with a view to popularize the literature of Bengal. To the effect that in a community like the one we are interested in, which is developing rapidly in intelligence and learning, it was necessary to set up a high ideal and work up to it." (Kumar, 1415 BE).

It is a fact that Bankim Chandra became associated with it in minor ways, as he seemed to have consented to review one of its books for publication. However, he was in failing health at the time the Academy began functioning (he would die the next year), so it is doubtful if his association had time to go deeper. The first Executive Committee of the Academy was formed by the following: President: Binaykrishna Deb, Vice Presidents: Hirendranath Dutta and L. Leotard, Secretary, and Accountant: Kshetrapal Chakraborty.

Although none of the above except Hirendranath Dutta was widely known as a writer, many members attending the weekly 'sessions' have names that stand out, such as Ramesh Chandra Dutt (novelist, 1848-1909), Sarat Chandra Das (anthropologist, 1849-1917), Trailokya Nath Mukhopadhyay (author), Nabagopal Mitra (swadeshi activist), Debendranath Mukhopadhyay (critic), Manomohan Basu (playwright), Chandi Charan Bandyopadhyay (Vidyasagar's biographer), etc.

Some luminaries in oriental scholarship, later referred to as 'Indologists', and highly-placed officials were also invited to be associated with the Academy as Honorary Members. Among them were George Birdwood (India Office, London), Frederick Max Muller, Sir Monier Williams, Sir Edwin Arnold, and Sir W. W. Hunter. They all responded happily and showed interest in the Academy's growth. Along with them, a large array of awe-inspiring names from the Bengali cultural elite have been associated with the growth of the Parishad, including Ramendrasundar Trivedi, Haraprasad Shastri, Rabindranath Tagore, Jagadish Chandra Basu, Acharya Prafull Chandra Roy, Basanta Ranjan Roy Bidvadballabh, Jogesh Chandra Roy Bidhyanidhi, Rajani Kanta Gupta, Sarada Charan Mitra, Nabin Chandra Sen, Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay, Nalinikanta Bhattashali, Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar, Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Sushil Kumar De, Ramaprasad Chanda, Abdul Karim Sahitya Bisharad, Abdul Gafur Siddiqui, Denesh Chandra Sen, Bidhusekhar Bhattacharya, Harekrishna Mukhopadhyay, Sahityaratna, Sukumar Sen, Sajani Kanta Das, Brajendranath Bandyopadhyay, Jogesh Chandra Bagal, etc. The later position-holders of the Parishad, worthy men no doubt, do not possess the luminescence of the above, which perhaps was to be expected. A library was added to the Academy on 29 October, 1893, which consisted mostly of books and journals from the members' personal collections. Sessions were held every Sundays, in which the tasks of the Academy were further elaborated in papers read by scholars. Kumar (35-36) lists them, which we arrange according to areas of concern—

Linguistic: A full dictionary of Bengali, divesting it of unnecessary Sanskrit words; a scientific grammar of Bengali; a history of the evolution of Bengali, collection, and explanation of personal names, place names, and rivers of Bengal.

Historical and Archaeological: collecting, preserving, and recording edicts and historical relics, etc., discovered in Bengal.

Folkloristic: Collection, preservation, and publication of fairy and folktales, fables of the Bengal region.

In this connection, we may refer to Rabindranath Tagore's 1312 BE address to Calcutta University Students titled 'Chhatrader Prati Sambhashan' which adds more information: collection of dialect materials, descriptions of folk-religious practices, etc.

In 1908, the Parishad moved to its own house on what is now Acharya Prafull Chandra Street near Maniktala, on land donated by Maharaja Manindra Chandra Nandi of Kandi. The house has now become a heritage building.

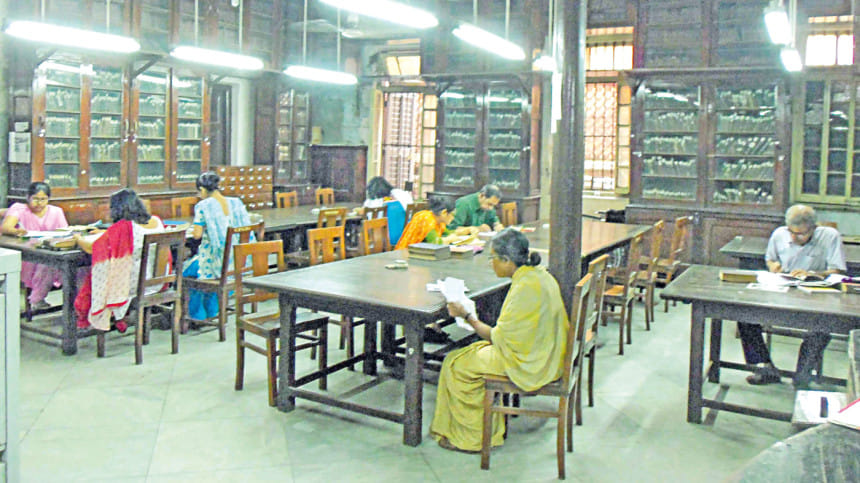

So far, our narrative has covered the early history of the Institution. Now it is our turn to look at the way it has evolved, for better or worse.The area where the Parishat has excelled in is the development of a library in which rare books and journals are preserved, some of which are not available elsewhere. An extremely valuable Vidyasagar collection has found its way here. The list of other valuable collections can be from the Parishat's website, which however, is not perfect. The major point is, it has an unique storehouse of nineteenth century periodicals and journals, and also of books of the time, whose number exceeds one lakh. The library is its most vibrant and intensely used service sector.

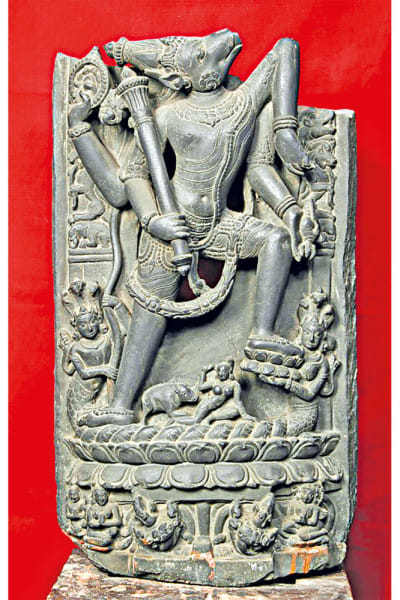

The Parishat also boasts a proud list of great publications, particularly those concerning old and middle Bengali literature. The Charyapadas, which carry the first samples of the earliest Bengali, is one such publication (1916). It was edited as Hajar Bachharer Puratan Bangala Bashay Bouddhagan O Doha by Haraprasad Shastri, who had discovered it in 1907 at the library of Nepal's Prime Minister. Another example is Shrikrishnakirtan, collected (1909) and edited (1916) by Basanta Ranjan Bidvatballabh.

The second book presents what is called early middle-Bengali, and together, these two have pushed back the history of the Bangla language by some five hundred years compared to what was marked for its beginning by earlier historians.

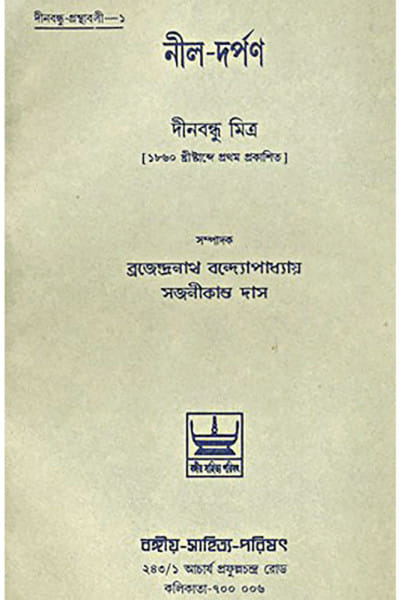

There are other valuable publications, mostly of middle Bengali texts, of various recensions of the Ramayana in Bangla, and some Mangala Kavyas. The collected volumes of Rammohan Roy, Biharilal Chakraborty, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Hemchandra Banerjee, etc., are notable among classics of the nineteenth century. Vidyasagar's works are conspicuous by their absence. However, given the changes in editorial practices over the decades, all of these publications need to be re-edited, employing modern editing theory, which the authorities of the Parishat have not paid requisite attention to so far.

Another useful series is the 'Sahitya Sadhak Charitmala', which offers small, critical life sketches of the men (and women) of letters of Bengal. The latest one to be published is that of Rabindranath Tagore. It suffers from the unforgivable omission of an 'index,' which once again shows a lukewarm attention to editorial care. Sambadpatre Sekaler Katha, two volumes with organized collections of highly useful paper-clippings of the nineteenth century prepared by Brajendranath Bandhyopadhyay, represents another important publication.

On the flip side of the coin, several promises have not been fulfilled. No dictionary of any size or denomination has been produced yet. An encyclopedia called Bharat Kosh was brought out in four volumes in the sixties of the last century, for which a central Government grant was received. But, as one knows, encyclopedias lose their value if not regularly reviewed and reissued. The Parishat journal, Bangiya Sahitya Parishat Patrika, first published in 1901, has become less and less regular, now appearing a volume a year. A hotly debated seminar was held in the same year on the 'Grammar of 'actual' Bengali,' with the participation of greats like Haraprasad Sastri, Rabindranath Tagore, Dwijendranath Tagore, Hirendranath Dutta, and quite a few Sanskrit scholars, but no grammar, like the dictionary as mentioned above, was produced as a result. One could therefore claim that it was the Bangla Academy of Dhaka that finally produced such a grammar around 2012, of what is called 'Pramita Bangla' or the Standard Colloquial Bengali. Sessions are held now few and far between, and endowment lectures are regularly held, but no seminar has so far been sponsored that could surpass the memory of the one held in 1901.The Parishat has been receiving State support for long, which amounts to fifty lakhs a year. On its centenary year it also received some special funding. Around 2012, it received a windfall, an endowment of about Rs. 5 crores from the historian Nimai Chatterjee, who was located in London. From its interest, the Parshat has acquired Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay's Kolkata residence where a Tarasankar Museum has been started, but has not opened for the public yet. There is an additional plan to shift the Parishat's publication department there.

The present authorities of the Parishat consist of well-meaning and competent individuals. However, the present time often finds itself helpless when compared to the glory of the past. Nevertheless, it is hoped that with the relative financial independence acquired, the authorities of the Parishat will achieve some exciting accomplishments in the near future. Some early promises still remain unfulfilled.

Author's note: I am indebted to Madan Mohan Kumar's book Bangiya Sahitya Parishader Itihas, Pratham Parva, 2008 (2nd Edn. Bangiya Sahitya Parishat) for reconstructing the early history of the organization.

Pabitra Sarkar is an author and former Vice Chancellor of Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments