Writing the Good Fight: Women, War, and Jahanara Imam’s Ekattorer Dinguli

In 1938, as Hitler marched across Europe, Virginia Woolf, in Three Guineas, urged women to "maintain an attitude of complete indifference" to war. She took a clear position on whether or not women have a stake in politics and war. But is it possible for women to remain indifferent to war? What if the war is waged to remove the oppressive conditions of a suffering people as was the case with the Bangladeshi liberation struggle? Where is the acknowledgement of the potential for freedom, for genuine historical transformation, in modern political movements?

Women are inherently bound up with these struggles. Besides, what if a woman's family members were soldiers in such a war? Under such circumstances, it is unlikely that she would decline to take part. It is one thing for a woman to be repulsed by jingoistic military displays as Woolf was, but quite another to assume that there can be no struggle worth waging. At the receiving end of Pakistan's exploitative sub-colonial domination over its eastern wing, Jahanara Imam's situation demanded her involvement. She could not sit by while the army from West Pakistan raped, tortured, and murdered her fellow citizens. Indifference or pacifism under the conditions prevailing in the country would amount to support for the aggressors.

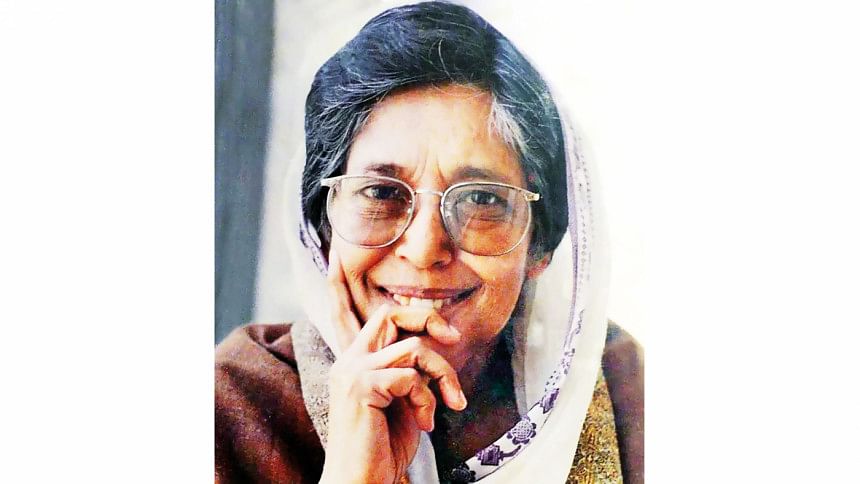

Jahanara Imam (1929-94), together with the rest of her family, was deeply invested in national affairs: her older son, Shafi Imam Rumi, was a freedom fighter; her husband, Shariful Imam, assisted the guerilla operations with maps and target identification; and her younger son, Saif Imam Jami, served as a lookout to ensure the safety of the freedom fighters as they entered or left the house. Imam herself conveyed information for the liberation warriors, in addition to providing nourishment, funds, necessary supplies, and protection at considerable personal risk. She recruited friends and relations to deepen and disperse support for the Mukti Bahini. Further, she endured enormous personal losses in the freedom struggle: the arrest and subsequent disappearance of her older son and the interrogation and torture of her younger son and husband, who died three days before the war ended.

Revered widely as Shaheed Janani (Mother of Martyrs), in the 1990s Imam organized the Ekattorer Ghatak-Dalal Nirmul Committee to bring to justice war criminals and collaborators of the 1971-genocide. As the convener of this body, in 1992 she was charged with sedition by the BNP government. The following year, while addressing the public with updated findings of the Committee, she was assaulted by the police.

Compiled from daily diary entries made during the 1971 war, Imam's memoir Ekattorer Dinguli (Days of '71) presents a poignant eye-witness account of the country's nine-month freedom struggle, blending a personal narrative with the political destiny of the nation. The narrative ranges from her shock upon discovering bomb component and two large mortars and pestles (to grind them) stashed in Rumi's closet; to her realization that thousands of plain-clothed soldiers were being flown to East Pakistan and ships packed with weapons were arriving at Chittagong harbor while fruitless talks continued between political leaders Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Yahya Khan, and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto; to her agony following her decision to grant Rumi permission to join the war; to rearranging the furniture in her living room to give greater cover to guerilla freedom fighters sheltering in her home; and, finally, to the raising of the Bangladeshi flag. Reviewing the English translation of Ekattorer Dinguli, Philip Hensher writes in The Guardian, "Just as the Holocaust needed a Diary of Anne Frank that brought the numbing total of deaths down to an individual, human case, so the Bangladeshi massacres are brought down to the feelings of a mother for her son" (March 1, 2013).

Imam was a full participant in the political struggle of her day. Despite her staggering bereavements, she had a stake in the freedom movement. Her loving and maternal attachments, as powerful as she feels them, do not preclude this fact. Indeed, they nurture it. The question cannot simply be, is revolutionary struggle good or bad for women? Doubtless, insofar as the regulation of women's bodies and sexuality are concerned, nationalism has repeatedly had catastrophic consequences for women in South Asia and elsewhere, as has colonialism. But what Imam could not ignore was that, as the Bangladeshi freedom struggle developed, it opened up the prospect that social issues, including but not confined to women's issues, could be more substantively addressed.

Ekattorer Dinguli

Last night, all of us stayed up, again. Sounds of gunfire, columns of fire, smoke swirling upwards. In the morning, the sound of gunfire paused for a while… When at eight-thirty, they made a radio-announcement regarding the lifting of the curfew, Rumi and I set out in the car… When we reached the vegetable sellers' area of New Market, Rumi hit the brakes with "Oh God"! The entire market was gutted by fire. Parts of it still smoldering. I screamed, "Look, there are charred human bodies too…" Rumi said, "Amma, don't look" and turning right on Mirpur Road, sped away…

Ekattorer Dinguli is a crucial historico-literary document of the war. It presents firsthand accounts of violence as part of an effort to organize a politics of liberation. To maintain historical accuracy, Imam fact-checked using eighty audio tapes of interviews with Rumi's surviving cohorts and other participants, especially, the details of the guerilla operations. She mentioned in later interviews that she was aware of the risks involved in keeping a journal that included details of guerilla activities and that she adopted different strategies to conceal the contents. She inserted into her daily logs irrelevant, even trivial, minutiae, giving the impression that her journal was nothing more than the ramblings of a bored housewife. She wrote in code—six sarees in place of six rifles—and concealed soldiers' identities by changing their names. Finally, she wrote forming geometrical patterns and using pens with inks of different colors to give the journal a look of triviality.

The memoir begins on March 1, 1971, when after Mujib's electoral victory Yahya Khan declared an indefinite postponement of the convening of the National Assembly, and it continues to December 17, 1971, the day after the Pakistani Army's surrender. Through its successive daily entries, it weaves details of domestic life into the contemporary political situation, with Imam's older son, Rumi, dominating the narrative. His involvement in leftist student politics, his decision to join the Mukti Bahini, his training, the actions he leads, and, finally, his capture constitute key events in Ekattorer Dinguli.

In her entry for April 21, Imam narrates granting Rumi permission to enlist in the Mukti Bahini. After rejecting his repeated appeals, reminding him that he is scheduled to start college in the United States that September, Rumi turns her refusal to let him participate in the war into a moral issue. Like many a young man before him, he states that his non-participation will forever weigh on his conscience. Eventually his mother gives in, "I shut my eyes tightly and said, 'Alright, I concede. I sacrifice you to the country. Go, enroll in the war.'" And, with that, the entry ends.

The sparseness of Imam's description, its matter-of-factness, evokes through its understatement the personal costs of war even as it powerfully conveys the sense of being caught up in events. The text packs its powerful emotional charge precisely through its exactness. At the time she wrote the diary, she knew that her twenty-year-old son was running a terrible risk and was afraid for the harm that might befall him. When she compiled the text for publication, she had experienced the worst. Exercising tight control over her pen, Imam conveyed her loss and, by implication, the suffering of innumerable others by euphemism, understatement, and silence.

The gravity of Imam's narrative is interspersed with moments of grim humor. One such is her encounter with a Pakistani soldier just as she prepares to send winter supplies to the freedom fighters:

Last week, as I was bargaining over six sweaters, a military-man patrolling the sidewalks approached me, "Why are you buying so many sweaters, Ma'am? To send to the young fighters?" I felt my heart jump to my throat, but managed a smile and replied [in Urdu] "Yes son, didn't Begum Liaquat Ali announce in the papers to buy sweaters, towels, soaps, blades, toffee, chewing gum for our soldiers and send to the APWA office? You know what the APWA office is, don't you? The All Pakistan Women's Association …" I stressed the "All Pakistan" part. Who knows what the chap understood, he simply nodded his head saying "Yes, of course" and left.

Unsettled by the soldier's question, Imam deftly switches to Urdu. She also manages to bring up a prominent West Pakistani figure, Ra'ana Liaquat Ali, the wife of the country's first prime minister. Cleverly re-interpreting his query, she manages to address the enemy soldier as "son."

***

The passionate support that the nationalist cause garnered must be viewed in conjunction with anti-colonial nationalism and the radicalism of the Bangladesh movement. It was a progressive struggle and one that could hardly be conducted nonviolently. The overwhelmingly popular leader of East Pakistan, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was frozen out of Parliament, the election results disregarded, and all attempts at negotiation scuttled. Moreover, the Pakistani army occupied the country. The struggle was democratic not only in the sense of being popular, but it also promised a substantial reordering of society. No one was immune to the main political question, millions felt they had a stake. This was true of men no more than women, who were, of course, represented in every group and class.

Further, the freedom struggle also presented a challenge to patriarchy. The nationalist movement directed its energies at removing oppressive social and cultural demands made on the Bengali population by the Pakistani state. For instance, aiming to establish a "national identity" between the culturally different populations of the eastern and western wings of Pakistan, the state insisted on reforming Bengali women's dress. On the resistance to this impulse, Naila Kabeer notes, how "the dress and deportment of Bengali women took on increasing symbolic value as expressions of their cultural difference" and that "the right to sing the songs of Tagore and to wear bindis became acts of political dissent" ("The Quest for National Identity: Women Islam and the State in Bangladesh"). The left-dominated struggle for Bangladeshi autonomy was simultaneously a demand for elementary civil liberties. The freedom struggle entailed the freeing of women's bodies and sensibilities in the most quotidian domains.

The mass sexual brutalities visited upon East Pakistani Bengali women by Pakistani soldiers likewise drew women qua women into the liberation movement. The freedom struggle encouraged women's participation and garnered wide support from them.

***

I close with an excerpt from Ekattorer Dinguli that evokes Imam's multidimensional involvement in the revolutionary politics of her country, both as nurturer and protector: One evening when she and her husband were sitting in their garden, two guerillas arrived to collect information her husband has compiled on bridges and culverts in the country (as possible targets for guerilla operations):

When Sharif glanced at me, I rose and went inside … the dining table was uncluttered, the curtains were drawn. Going into the kitchen, I told Qasem, "Sauté four shammi kebabs and two croquettes right away." From the refrigerator, I took out the rasmalai and, putting some in a bowl, I further instructed him with, "In about fifteen minutes, once you're done sautéing, arrange the refreshments on a tray, and place it on the dining table along with quarter plates, cutlery, and water. I won't come in again. Do you understand?"

I went back outside and looked around. I saw no one at the windows of the nearby houses, the road too was deserted. I said to Sharif, "Go sit at the dining table." The three of them went inside, while I sat in the garden keeping watch over the gate. My heart was pounding. I ached to join them. To hear from them, about Rumi. But I couldn't leave the gate unguarded. Jami couldn't find a worse time to fall sick.

It was darkening. Sajjad, the son of Reza Saheb, … came to the gate, "Auntie, I need to use the phone." I lied, "But it isn't working." As soon as he left, I rushed inside. If someone calls right now, it'll be a problem. Climbing to the second floor, I dialed "1" on the bedroom extension and put the receiver down without returning it to the cradle.

With her younger son Jami indisposed, Imam assumed the task of keeping the premises safe for the two guerillas. The next morning, she rearranged the furniture in the living room to create a partition between the living room and the dining area. This gave the dining area greater privacy by shielding from the view of any unexpected visitor, the liberation warriors sheltering in her home. Though she did not, as many women did, carry a gun and become a soldier in uniform for her country, her very lack of uniform made her most valuable for the cause.

(All translations from Ekattorer Dinguli have been done by the author.)

Debali Mookerjea-Leonard, Ph.D., holds the position of Professor of English and World Literature, as well as Madison Scholar, in the Department of English at James Madison University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments