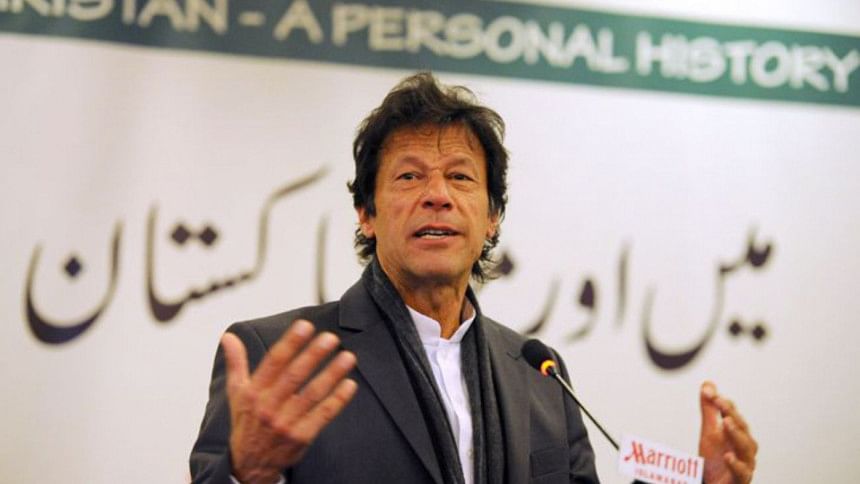

Imran Khan's biggest challenge? 'It's the economy, stupid!'

Shakespeare had once observed, through his character Marcellus addressing Horatio in the drama Hamlet, that there was something rotten in the State of Denmark. Thereafter, he sought to analyse those remarks by weaving an incredibly complex scenario that focussed on the woefully morbid persona of his brooding and indecisive hero, Prince Hamlet. Were the English bard to return to the present times and be asked on his view as to what ails contemporary Pakistan, he would perhaps respond, with incontrovertible logic and certitude, that it is the economy. Prime Minister-elect Imran Khan would agree. Mr Khan would also conclude that the indecisiveness of the young Dane would be a luxury that he could ill afford.

Mr Khan cannot be faulted for any absence of zeal during the preparatory process, leading up to the polls, to go about this task. In his election manifesto issued early July, he entitled his aspirations as the "Road to New Pakistan". It was, if not influenced by but certainly reminiscent of, a similar document of the British Labour Party of Mr Clement Attlee in 1945 called "The New Jerusalem", based on a mystic poem by Robert Blake. Mr Attlee set these as goals for post-war Britain. He used it effectively as a tool to unseat the war hero Sir Winston Churchill, despite the latter's derision, belied by the election results, that Mr Attlee was a "modest man with much to be modest about!" In Pakistan, Mr Khan rendered his plans more attractive to his right-wing supporters by stating that his idea was to emulate the state apparatus emplaced in the city of Medina in the seventh century by the Holy Prophet, as components of an "Islamic welfare state". To his more contemporary constituency, he explained the model as being similar to the politico-economic culture prevalent in Scandinavia. The explanations seemed to have gone down well with the electorate.

The big challenge to Mr Khan will be as to how this is to be implemented. Alas, the road to a "New Pakistan" appears to be extremely uneven, unusually steep, and full of potholes. That is because he has unfortunately inherited an economy that is, by all accounts, in shambles. The World Bank estimates that Pakistan's growth rate will be only 5 percent in 2019. This is not above India's so-called "Hindu growth rate" of yesteryears (which would be a bitter pill to swallow in Pakistan). Pakistan's foreign exchange reserves have plummeted to USD 9 billion. This is less than a third of that of Bangladesh, which is often held out by analysts as a frame of reference. It is just about sufficient to finance two months of imports instead of three, which is the norm for comparable countries. The rupee is in free fall, devalued four times over the last six months, and is now at a rock-bottom par of 128 to the US dollar. The 200 or so state-owned enterprises in Pakistan (SOEs) are inefficient, mismanaged, politicised, and corrupt, costing the national exchequer well over half a trillion rupees. Direct taxes amount to a mere 11 percent of the total collection. Less than 1 percent pay income tax. These numbers are enough to daunt any incoming government anywhere.

The "Team Khan"— including Mr Asad Umar, the likely finance minister—have plans. Mr Umar is an extremely qualified technocrat-turned-politician who was once the highest paid CEO in the land. They will seek external funding, possibly an over USD 13 billion credit from the IMF, some of which will be used for paying off debts. China, which Mr Khan extolled as perhaps Pakistan's closest friend, will also be approached. Of course, any IMF balance-of-payment support will come with restrictive conditions likely to dampen the enthusiasm for public expenditure for social sectors. Mr Khan, however, may be intellectually persuaded that a "government must do what a government must do". The SOEs would be depoliticised with experts brought in to head them, as well as to fill government posts where deemed fit. Ministries would be streamlined, their numbers in the federal structure reduced from 37 to 17. The Federal Board of Revenue would be made autonomous, perhaps somewhat like the Central Bank. They would be urged to increase tax collections up to 5 percent of the GDP. Five percent of the GDP would be spent on education within five years, in place of the current 2 percent, to create a pool of schooled girls and boys. A new agriculture policy will be designed to optimise subsidies (not necessarily increase), reduce input costs, and provide credit.

A sticky wicket for this legendary cricket captain would be handling the military finances. The implementation of Mr Khan's "five-point emergency plan", the initial phase of his overall programme, would logically entail reduction of the army budgetary allocation. Currently, it stands at USD 9.6 billion, nearly 20 percent of the total national budget. Any downsizing would need to be carefully balanced by perhaps an augmenting of privileges to the uniformed through what the writer Ayesha Siddiqa has critically called the "Milbus", or providing business opportunities to the military. Indeed, Mr Khan's overall relationship with the military will be an important element as to how his governance will pan out. He is said to have the blessings of the army, far more than what is enjoyed by his rivals. It is also true that the army does not have too much choice. Mr Khan is a strong personality. Moreover, he is also popular. If things work out for him, he may become more so in the future. Many of his views coincide with those of the military. But there are also some differences, as with regard to military action in the Pashtun frontiers. Mr Khan and the army need each other for now, and both are well aware of this reality.

To lift Pakistan up from the economic morass, trade would be key. Mr Khan has emphasised this aspect while mentioning his relations with India in the post-polls speech. The figures currently are abysmally low. There are many common elements between Messrs Khan and Narendra Modi of India. Both possess tremendous self-confidence in their self-assessments. Mr Dayan Jayatilleka, a Sri Lankan scholar and diplomat, once a colleague of the author in Singapore, has written: "South Asian politics had only one charismatic star in the firmament… now it has two." When they meet, as they perhaps will sooner than later in this era of "surprise summits", the region and the world may see the adage play out—that "when Greek meets Greek, then comes the tug of war!" The other important protagonist would be the United States. As of now, Mr Donald Trump has demonstrated remarkable self-restraint by not tweeting his initial thoughts on Mr Khan.

As one awaits the unfolding of further political developments in Pakistan, Mr Khan's capacity and capabilities are being meticulously scrutinised. His second wife Ms Reham Khan has recently published a book which contains an elaborate laundry list of Mr Khan's shortcomings. This was doubtless timed to do damage to Mr Khan's reputation and electoral ambitions. However, not many Pakistanis seemed to have taken note. In it, Ms Reham Khan, among other things, has accused Mr Khan of ignorance. To make her point, she has said that she was baffled by his unawareness of the fairy tale of Rapunzel. In this children's story, a princess had laid down her long hair from a window in a castle in which she was imprisoned to enable a handsome prince to climb up to rescue her. Mr Khan might not have been clued in on this detail. But he was nevertheless, in the meanwhile, creating his own fairy tale by climbing the ladder of power reaching up to the highest public office of his country.

Dr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury is a former foreign adviser to a caretaker government of Bangladesh and is currently Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore.

Comments