Delhi's psychedelic face masks

I was in Delhi last month, partly for work and partly to devour the winter delicacies. Lately this city has been in the news for all the wrong reasons. One of them is air pollution—both the print and electronic media emphasising once more that it had again reached hazardous levels. Well, the poor air quality during winter months in Delhi and other large South Asian cities is not a new phenomenon. While the health impact is magnified due to atmospheric factors, humankind remains the main contributor.

What was interesting for me was seeing the way people were getting ready for the air pollution; a variety of face masks came out as we landed in Delhi. The masks were of different shapes, sizes and colours. Some were paper thin, some were more sophisticated, looking like they were not only ready to combat the air pollution, but support the colonisation of Mars or defend the Siachen. I was wondering if the paper-thin masks would work beyond having a placebo effect. The holes in the thin paper masks perhaps do not do anything to reduce the exposure to the fine particles.

While waiting in the immigration queue, I noted that some women were carrying masks colour-coordinated with their shoes or shawls. It could be quite coincidental or maybe I imagined it because of the lack of oxygen in my brain due to the long flight.

After completing the formalities and leaving the airport, I observed people putting on their masks while waiting to be picked up. Inside the airport I was more amused by people's preparation for dealing with the air pollution. The amusement diminished and bewilderment sipped in when I saw the number of people wearing masks outside. Where were we heading?

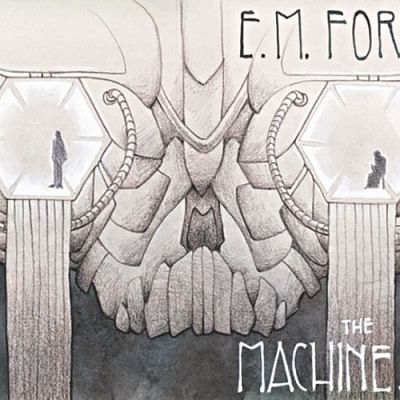

The masked faces reminded me of the famous short story "The Machine Stops" by E. M. Forster published in 1909. It is a chilling science fiction describing our role in a technology-dependent environment. In the story, humankind had lost the ability to live on the earth's surface, and so individuals had to live underground, in boxes. People were given equipment to fulfil the basic requirements of life. The story is definitely more relevant today than it was when first published.

"Imagine, if you can, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee. It is lighted neither by window nor by lamp, yet it is filled with a soft radiance. There are no apertures for ventilation, yet the air is fresh. There are no musical instruments, and yet, at the moment that my meditation opens, this room is throbbing with melodious sounds. An armchair is in the centre, by its side a reading-desk—that is all the furniture. And in the armchair there sits a swaddled lump of flesh—a woman, about five feet high, with a face as white as a fungus. It is to her that the little room belongs." ("The Machine Stops", Chapter one).

A chill ran down my spine. I am not sure if it was due to the north Indian winter or due to the thought that in the near future we will live in cubicles and think: "this is our world". We already rely on bottled water—will we carry cylinders to breath pure air? Spending time outdoors in the toxic atmosphere will be discouraged, unless absolutely required. We will fear taking off our masks, any human contact will be dreaded. Our medium of communication will be buttons. Our brains and muscles will be weak. We will live exclusively through "electronic devices".

In the story E. M. Forster writes: "… then she generated the light, and the sight of her room, flooded with radiance and studded with electric buttons, revived her. There were buttons and switches everywhere—buttons to call for food for music, for clothing. There was the hot-bath button, by pressure of which a basin of (imitation) marble rose out of the floor, filled to the brim with a warm deodorised liquid. There was the cold-bath button. There was the button that produced literature. And there were of course the buttons by which she communicated with her friends. The room, though it contained nothing, was in touch with all that she cared for in the world."

I shivered, again feeling the chill in my spine. I desperately hoped that it was due to the nippy air.

Anindita Roy is a public health specialist, working with an international organisation in Geneva, Switzerland.

Comments