Inside the unexpected, unstoppable Hong Kong

When she first heard about the infamous extradition bill on March 31 this year, Adrienne, a 24-year-old Hong Kong national, had lost hope. She had imagined that outrage would stoke up mildly, but indifference would soon overtake the impetus, because that was the outcome of the 2014 Umbrella Movement—protests after the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (of China) issued a decision regarding proposed reforms to the Hong Kong electoral system.

But this time, Adrienne has been proven wrong. For the past 11 weeks, she has been finding herself in protests, one after the other—its energy still unruffled, and the unity of discontent driving it, only intensifying by the day.

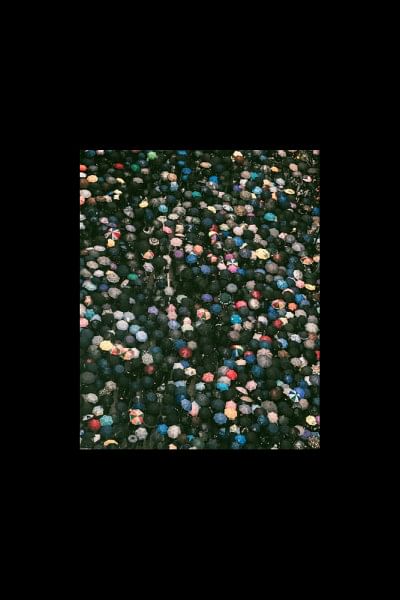

Whereas on August 14, 2019, a statement released by Hong Kong affairs office of China's state council hardened its rhetoric on the protests, labelling the demonstrators as "radical violent elements", an estimated 1.7 million HongKongers marched on August 18, 2019, as rain showered on Victoria Park and beyond—the saturated image of umbrellas flagrantly painting the scale of disillusionment. But if this enormous display of solidarity was unexpected even for HongKongers themselves, a question naturally emerges: what is so contentious about the 2019 extradition bill?

The existing extradition bill specifically states that it does not apply to "the Central People's Government or the government of any other part of the People's Republic of China." But the proposed changes would have extradited all criminal suspects to the jurisdiction of China, which has a dubious reputation for unfair detention, trial and torture of dissenters. For example, Jiang Tianyong—a prominent Chinese rights lawyer who had taken on many high-profile cases including those of Falun Gong practitioners and Tibetan protesters—is one of more than 200 lawyers and activists detained since 2015 in an effort to quell courtroom critics of Communist authorities.

So, the 2019 extradition bill was met with raucous rage as it was widely seen as a threat to the rights of all HongKongers; Amnesty International has said, "the proposed changes of the extradition bill, if enacted, would essentially allow the handover of persons in the territory of Hong Kong to mainland China. No one will be safe, including activists, human rights lawyers, journalists, and social workers."

The initial protests, where police heartlessly fired tear gas and rubber bullets at peaceful protesters, did, however, push the now-beleaguered Chief Executive Carrie Lam to suspend the bill "indefinitely" on June 16. The retraction perhaps came too late, or was rather unconvincing for HongKongers, who, according to Adrienne, "were too awakened by police brutality." When she had first fallen prey to pepper-spray, Adrienne had only an umbrella with her. So, she says, "it was made clear to me that even when I had no intentions of harming anyone, it was just illegal for me to even be there at the protests, to merely exercise my freedom of speech...if anything, the protests are now focused on resisting police repression."

Put another way, what started out as criticism for a controversial extradition bill, the parlance of Hong Kong protesters has since ricocheted into a larger, relentless fight for democracy.

Now, protesters have five demands listed in the pamphlets they have been handing out to tourists at the airport: complete withdrawal of the bill; executive implementation of universal suffrage in the chief executive and legislative council election; retraction of "riot" characterisation of the 612 protest; independent investigation commission to thoroughly investigate police brutality and withdrawing criminal charges against all protestors. The pamphlets also state that 44 protesters were arrested and prosecuted during the July 27 Sheung Wan protest for "rioting"—an accusation the protesters claim is entirely false.

On the other hand, Jim Bueermann, former President of Police Foundation in Washington, recently told the New York Times that firing tear gas is "hugely problematic…if it hits someone in the head, you could kill them."

Regardless, the tear gas and rubber bullets continued—even indoors, on escalators at a subway station in Kwai Fong—but as did much worse.

And we cannot leave out the sentiments of betrayal ensconced in this fight. On August 5, during a city-wide strike, Adrienne, along with many other protesters, had gathered in the small square that was warranted safety by the "letter of no objection"—which meant no one could be arrested or harmed for protesting in those particular spots—but around 7PM, police had allegedly violated their own terms by entering those very roads and firing tear gas, live videos of which were posted by individuals all across social media.

And on August 11 came another turning point in TsimShaTsui in Kowloon, when a footage emerged of a woman, believed to be a volunteer medic, lying on the ground with blood streaming from her right eye. Also appearing in the viral images at the spot where she was allegedly hit was a pair of goggles in which a beanbag round was lodged. The tragic event became a figurehead for the leaderless movement, and founded its symbolic catchphrase, "an eye for an eye." But beyond an eye, this movement has also cost lives: 5 people killed themselves in despair, all leaving notes that deplored the Hong Kong government. One of them read, "What Hong Kong needs is a revolution."

On another note, most narratives tend to leave out the sexual violence that is imbued in violent clashes as such, but now it's slowly unfolding in front of the public eye. On August 23, a Hong Kong woman who was arrested told the Hong Kong Free Press that a female police officer had conducted "an unreasonable full strip search without gloves, and of using a pen to force her to spread her legs."

And as it happens during political unrest, citizens become divided in their political views and hatred begins blowing in full force. A few hours before midnight on August 20, a man armed with a knife at a Lennon Wall in Tseung Kwan O—a message board where people can post notes about the protests—allegedly attacked 3 people and left a 26-year-old woman hospitalised in critical condition. An eyewitness told Apple Daily Hong Kong that the allegedly pro-Beijing male assailant had "asked what our views were about the Lennon Wall. It started as a peaceful dialogue, but later they were discussing something, and he suddenly shouted 'I can't take it anymore.'" The attack followed shortly afterwards.

On August 20, Lam said in a press conference that the extradition bill is "officially dead" but she maintains that the police are "safeguarding" Hong Kong and its people. Her words that eschew "complete withdrawal" translate her deceitful agendas to protesters. According to Adrienne, Lam's attempts at amelioration mean little when people still have to fear that the police will arbitrarily stop them on their way back home from school and arrest them for disloyalty. Despite all the repression, even as Chinese military crackdown becomes a frightening possibility, Hong Kong loudly refuses to be silenced.

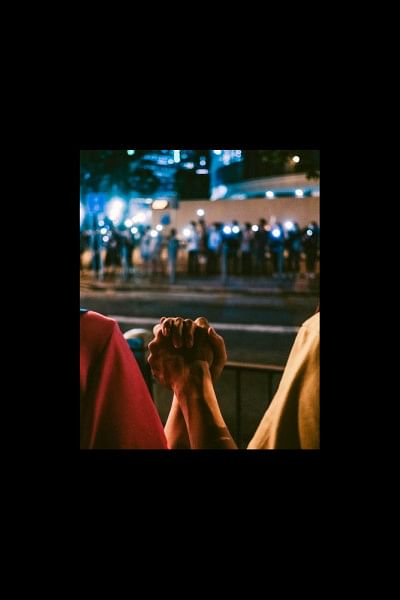

On August 23—the 30-year anniversary of the Baltic Way, when 2 million protestors formed a human chain across the 650-kilometer border of three nations, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, calling for independence from the Soviet Union—HongKongers gathered to form human chains all around the city, echoing, "tonight we have the Hong Kong way." With this extraordinary magnitude of civil disobedience, Hong Kong has shown the world the courage it takes to speak up for days on end. Whether those they're speaking to have the courage it takes to listen is yet to be seen.

Ramisa Rob is pursuing her Master's in New York

University. (Names of interviewees used in the article have been changed for their safety.)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments