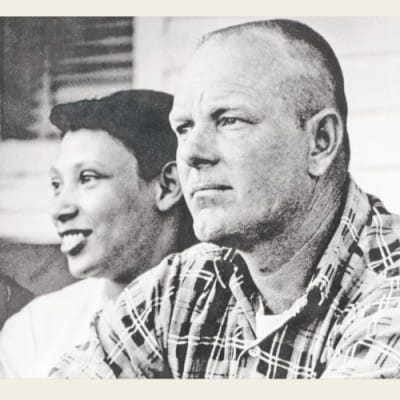

A story about loving, in black and white

A landmark US Supreme Court decision was handed down over 50 years ago this month, but more about that in a moment.

In its very essence, this is an extraordinary love story of two ordinary people. Mildred and Richard grew up in Central Point, a speck of a town in rural Virginia. When Mildred first met Richard, she was a skinny 11-year-old nicknamed "Bean", and Richard was a strapping 17-year-old teenager. Their friendship deepened over the years and led to courtship. When Mildred was 18, they drove 80 miles away to Washington, DC, to get married.

They returned home to Virginia to start a new life.

But soon disaster struck. At 2am in July 1958, a local sheriff burst into their bedroom and shined flashlights into their eyes. A threatening voice demanded: "Who is this woman you are sleeping with?"

Mildred replied that she was his wife, and Richard pointed to their marriage certificate.

The sheriff said their marriage certificate was no good in Virginia, giving the lie to the state's fond claim in publicity campaigns that "Virginia is for lovers."

You see, Mildred Jeter was black, while her husband, Richard Loving (yes, that is his real name) was white. In the 1950s, Virginia was one of 24 states whose anti-miscegenation laws made interracial marriage a felony.

The Lovings were charged with "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth."

Virginia trial judge Leon M Bazile ruled: "Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay (sic) and red, and he placed them on separate continents…. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix."

The Lovings were forced to plead guilty. They avoided prison by pledging to leave the state for 25 years. They moved to Washington, DC, but Mildred bitterly missed family and friends in Virginia.

So here you had a family, poor and working-class – Richard Loving was a bricklayer – helpless against the massive might of a state judiciary wedded to an implacably racist law.

Mildred did not give up. She wrote to erstwhile attorney general Robert Kennedy, who suggested she seek the help of the American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU took their case, and eventually it reached the US Supreme Court.

Fifty years ago this month, the US Supreme Court rose to the challenge. In a unanimous ruling written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the court enshrined the freedom to marry.

"Marriage is … fundamental to our very existence and survival," Warren ruled in Loving v. Virginia. "To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes … is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The 14th Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination."

Today, the ruling sounds like a no-brainer, but racial animus still ran deep in the US in 1967.

Some people had to be brought kicking and screaming into a brave new world of race-neutral equality. Two years after the ruling, Georgia's state legislature refused to hire former US Secretary of State Dean Rusk to teach at the University of Georgia because he had participated in his daughter's wedding to an African American. Some southern states clung to state laws banning interracial marriage. South Carolina repealed it in 1998, Alabama in 2000!

God knows America's struggle to achieve a colour blind society is still a work in progress. Outrage at recent police killings of African Americans with minimal or no penalties has given rise to the Black Lives Matter movement. Meanwhile President Donald Trump and his overt race-baiting – including his shameless promotion of the canard about former President Barack Obama's Kenyan birth – continue to rile up white racial rancour. The Republican Party has also been complicit.

Amidst this turmoil, however, there is cause for hope. In the 50 years since the landmark case, the rate of interracial marriage in America has increased five-fold from three percent in 1967 to 17 percent in 2015, according to a Pew Research Center report. As America becomes more diverse, larger parts of younger demographic cohorts are shedding the racial prejudices of their forebears.

Now let's return to the Lovings. Whatever became of them?

Mildred and Richard were an unassuming, down-to-earth couple. They did not even go to the Supreme Court hearings. "Tell the judge I love my wife and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia," Richard told his lawyer.

After the legal victory, Richard got his wish.

"Richard, by all accounts a stoic, blue-collar man content to let Mildred do the talking, moved his family into a small house on Passing Road, and tried to live happily ever after," the Associated Press reported in 2007, marking 40 years of the landmark case. "That ended when a drunken driver struck their car in 1975, killing Richard and costing Mildred her right eye. The small cemetery where he is buried is a few minutes from their home."

Mildred never remarried. She largely shunned publicity.

"Her hands are curled by arthritis and her right eye is just a lidded hollow now. Still, Mildred's face lights up as she talks about Richard. She thinks about him every day," the AP report continued.

"Each June 12, Loving Day events around the country mark the advances of mixed-race couples. Mildred doesn't pay much attention to the grassroots celebrations.

"Mostly she spends time enjoying her family, two dogs, and the countryside she fought so fiercely to again call home.

"She wishes her husband was there to enjoy it with her.

"'He used to take care of me,' said Mildred Loving. 'He was my support, he was my rock.'"

On May 2, 2016, Mildred Loving died in Central Point, Va. She was 68.

The writer is a contributing editor for Siliconeer, a monthly periodical for South Asians in the United States.

Comments