A requiem for the Sundarbans

Ted Hughes, England's former Poet Laureate who is better known as Sylvia Plath's delinquent husband, once penned a paean to the Sundarbans. In 1989, while visiting Bangladesh as an official guest of the Government, he took a leisurely trip down the Rupsa River. At Hiron Point, as his slow moving steam boat approached the Sundarbans, he was struck by the quiet beauty of the world's largest mangrove forest. Later he wrote the following lines, dedicating them to the Sundarbans:

I slept here a night of chaotic dreams,

I could not keep my dreams inside the rest-house,

They spread out through the forest,

Real tigers trod on them.

In the morning the sea

Was a bed of pink rose petals

Where somebody very beautiful had slept

A perfect sleep.

Not a particularly good poem, but the poet's adoration for the great Sundarbans is clear. Today, nearly three decades later, if he could visit once more, Ted Hughes would be shocked to see the slow death of his beloved forest. The Sundarbans is now a sad reminder of its past glories. Devastating storms have left much of the forest decimated. With sea levels quietly rising due to climate change, the mangrove continues to lose much of its salt-tolerant trees. For centuries these trees have offered protection from storms that lash out at regular intervals.

As trees disappear, so do tigers.

Now comes the promise of a coal-powered 1320 megawatt power plant, a joint venture between Bangladesh and India, to be built at Rampal near the Sundarbans. This year in July, the Government of Bangladesh celebrated the signing of a contract with India's Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited to build the plant by 2019, calling it a friendship project. The USD 1.49 billion dollar plant will be largely funded by India. Coal, its power source, will also be supplied by India, which already has more coal than it can make use of.

This could be the last nail in the Sundarbans' coffin.

Everybody, who is somehow not connected with the Bangladesh government, has opposed the construction of such a massive power plant so close to the Sundarbans. A civil society movement has sprung up in Bangladesh resisting the power plant. The initial opposition came from the local people who feared the loss of their livelihood. It was soon embraced by various environmental and human rights groups in Bangladesh and by a section of the academia. Once resisting Rampal became a potent political cause, the opposition BNP and Jamaat leaped to its support. That led the government to paint the entire Resist Rampal movement with a broad stroke, lumping them together as anti-government.

Ironically, resistance to Rampal comes not only from Bangladesh's home grown environmentalists but also from those in India and elsewhere in the world. A fact often glossed over by officials in Dhaka is that India itself had opposed such a power plant anywhere near the Sundarbans on its side. Dr Kalyan Rudra, Chairman of West Bengal Pollution Control Board, has called such a project "a red category industry." Given the amount of toxic substance the plant would emit, "there cannot even be a question of setting up such a plant near a reserved forest," he told a Dhaka newspaper.

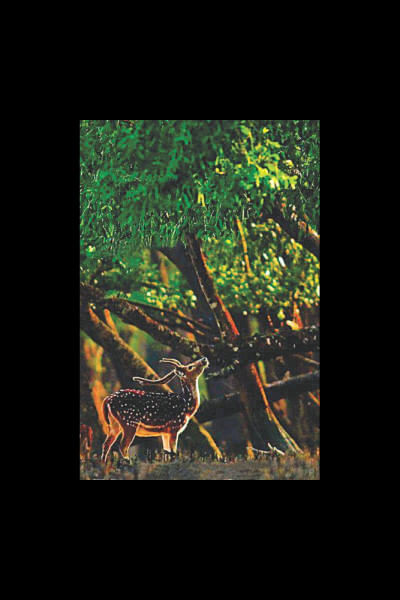

One of the fiercest oppositions to the project has come from UNESCO, keeper of the world's common legacy. In 1987, the world body, recognising its "outstanding universal value," designated the Sundarbans as a world heritage site. It described the Sundarbans as "one of the most biologically productive of all natural ecosystems." Its forests and waterways support a wide range of fauna, "including a number of species threatened with extinction." Among them is the Royal Bengal Tiger, which makes the Sundarbans its home. "The mangrove habitat supports the single largest population of tigers in the world which have adapted to an almost amphibious life."

UNESCO is unambiguous in its assessment of the impact of the Rampal power plant. This year in March, a three-member team from UNESCO visited the Sundarbans and later submitted its recommendations on the Rampal project. It concluded that there is a strong likelihood that the power plant, if built in the current location, would contaminate the air and water of the Sundarbans and its surrounding forests, and the substantial shipping and dredging and the removal of a large amount of fresh water would seriously impact the region's ecosystem.

Availability of water is one reason why the Rampal location was chosen. According to the project's own environmental impact assessment, water use at the plant could reduce the downstream flow of the Passur River by as much as 35 billion litres annually. Much of the water would later be discharged into the same river, only this time as treated waste, causing untold devastation to the nearby communities, mangrove forests and marine animals.

350.org, an international environmental group that opposes the project, has pointed out another important fact. To keep the plant running, Bangladesh will need to import about 4.72 million tonnes of coal each year. This coal, brought in by ships to the port some 40 kilometres away, will later be trucked to the plant using a route cutting through the Sundarbans. The environmental impact of such a massive operation would be devastating.

The Netherlands' BankTrack, an international think tank monitoring operations and investments of private sector banks, has been very specific in its arguments for opposing the project. The technology required at Rampal will emit 30 percent more sulphur dioxide than state of the art technology, it says. There are no technologies required at Rampal to specifically eliminate such harmful emissions, including those of mercury, nitrogen oxides, and chromium though widely available technologies exist to do so.

Avaaz, an international rights organisation, has also voiced its protest. In a mass petition campaign, it has urged UESCO to recognise the threat on the Sundarbans and to officially enlist it into the "List of World Heritage in Danger". It has also urged the world body to take concrete and deliberate action to ensure the future protection of the forest from commercial activities.

UNESCO's response has been clear. It has advised Bangladesh to cancel Rampal and move the power plant to a location that would not impact negatively on the Sundarbans.

Why is the Bangladesh government so determined to go ahead with a project that every sane-minded person not affiliated with the government thinks will do more harm than good? In September, I put this question to the members of the delegation accompanying Prime Minister Hasina who was in New York for the annual UN General Assembly. One of them, speaking on behalf of the group, replied with a counter question: Do you think our Prime Minister would do something that would go against our national interest?

We certainly hope not.

The writer is a journalist and author based in New York.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments