Elections in tea gardens and the larger issues of tea workers

Election of Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU) on June 24 was a joyous occasion for tea workers. BCSU happens to be the largest trade union in Bangladesh. And it is the only union for the 97,646 voters who are all registered workers in 161 tea gardens in Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chattogram and Rangamati Hill District. The recent election was the third time since 1948 that the impoverished tea workers had voted for their leaders.

The first time they were allowed to vote by secret ballot was in 2008. At the time the daily pay of a tea worker was only Tk 32.50. The second election took place on August 10, 2014 when the daily pay had risen to Tk 65. In both elections, Rambhajan Kairi and Makhonlal Karmokar's panels had won landslide victories. To no one's surprise the results this time were the same.

Like in the past two elections, the Department of Labour (DL)—a state agency—conducted the election with an election commission headed by Shib Nath Roy, Director General (additional secretary) of DL under the Ministry of Labour and Employment. And the elections were carried out very well.

Tea workers seemed to be in high spirit on election day. Nearly 97 percent of voters showed up to vote and had no problem electing their candidates of panchayets, seven valley committees and the central committee of BCSU.

The central committee of BCSU is composed of 35 members—eight directly elected (president's and general secretary's panels) by voters, 22 presidents, vice-presidents, secretaries and organising secretary (only of Balishira Valley) from seven valleys (two from Balisira considering its large size compared to others), and five nominated by the losing panels of president (three) and secretary (two).

Rambhajan Kairi, elected general secretary for the third time, is happy about the elections. He was at the forefront of a youth-led campaign against Rajendraprasad Bunarjee and allegedly a central committee of his choice who controlled BCSU and its central office located in the Labour House from 1970 to 2006. No democratic elections were held during this time. "The tea workers have voted three times in BCSU and in support of our ongoing struggle for rights," said Kairi.

Why is the government in a trade union election?

The Labour Law of 2006 considers the tea industry as a group of establishments and allows tea workers to unionise only at the national level. To form a union in the tea industry, 30 percent of the total workers must be members. Now that all registered workers have been made members of the lone union, it is unlikely for there to be a second trade union in the tea industry should the current situation persist.

What is most appalling is that BCSU remains isolated from unions, federations or confederations outside the tea industry.

"There is no precedence in recent history of the government conducting an election of a trade union in any other industry with funding support," said Tapan Dutta, president of Trade Union Center in Chattogram and a close associate with BCSU.

Rambhajan Kairi, the winner has his contention: "The government has conducted our elections because we still have not developed our capacity to conduct elections of such a large union."

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed, a trade union expert and Executive Director of Bangladesh Institute of Law and Labour Studies (BILS) believes that given the conflicting situation in the tea gardens, the government may come forward to assist. "But I do not know if the government has conducted election of a trade union in any other industry with funding support," frowns Ahmed. He suggests that only one union for the entire tea industry is not desirable. The labour law should allow formation of trade unions in at least the valley level, if not at garden level. The 161 tea garden (excluding the ones in the north Bengal) are split into seven valleys.

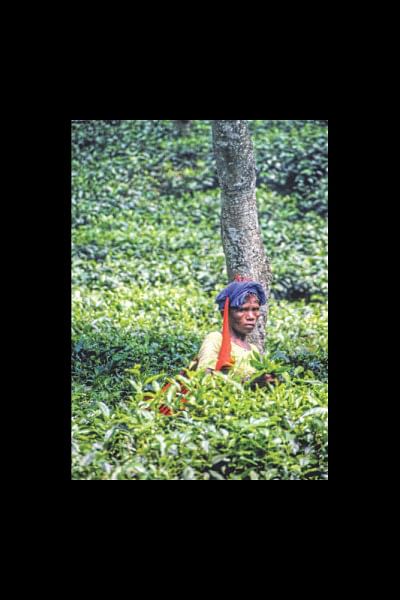

The larger issue of the tea workers: deprivation

The larger issue beyond elections of BCSU is the deprivation of tea workers that must end. The tea industry is an industry where no tea worker gets an appointment letter and no gratuity upon retirement or end of job. Unlike other industrial workers, tea workers get no casual leave. The single most significant issue of deprivation is "unjust" wages—Tk 85 per day.

The deprivation of tea workers for four generations has deep roots. The majority of them, non-locals, belong to as many as 80 communities. The British companies brought them from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens of Sylhet region. The misfortune of these indentured laborers started with their journey to the tea gardens that begun more than 150 years ago. According to one account, in the early years, a third of tea plantation workers died during their long journey to the tea gardens and due to difficult working and living conditions.

To the majority of people in Bangladesh, they thus remain invisible. They sometimes treat them as aliens and are therefore indifferent about their plights and rights as equal citizens. These provide the perfect conditions for owners of tea gardens to continue exploiting them.

The state and people of the majority communities have a responsibility towards tea workers. There are allegations from different sources that state agencies and law makers are not thinking and doing enough to end the discrimination in the labour law against tea workers and are maintaining the status quo by not-implementing the labour law.

On the cultural front, tea communities, excluded and disconnected, have lost their original languages in most parts as well as their culture, history, education, knowledge and unity. They deserve special attention from the state, besides equal treatment, which go far beyond a well-managed election like the one we saw on June 24.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on tea workers and the tea industry for more than a decade. The writer acknowledges the contribution of Rabiullah in writing this article.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments