Rohingya crisis: Issues and challenges that have emerged

To date, much has been written and said about the Rohingya crisis. The regime in Naypyidaw has literally flouted all international laws and evaded pressures from the international community. Myanmar is now accusing Bangladesh for the delay in repatriation and at the same time plotting more atrocities against Rohingyas in Rakhine state. Last week, the Rakhine state government issued notice further blocking the United Nations and other aid agencies from travelling to five townships affected by the conflict. Sadly, many believed that the agreement for repatriation signed back in November 2017 will take care of this human tragedy.

We must not forget that the Rohingya crisis is trapped into many strands of regional and international politics. The new foreign minister AK Abdul Momen, in his debut statement on the Rohingya crisis, said that the "much-talked-about Rohingya issue will not be solved easily." The foreign minister referred to this international tangle, and remarked that "interest of everybody including India and China will be hampered," if the Rohingya crisis continues. The foreign minister further urged the international community "to step forward for a logical solution to this crisis." The foreign minister also directed to conduct a study to understand the impacts of Rohingyas on Bangladesh economy, society and security systems.

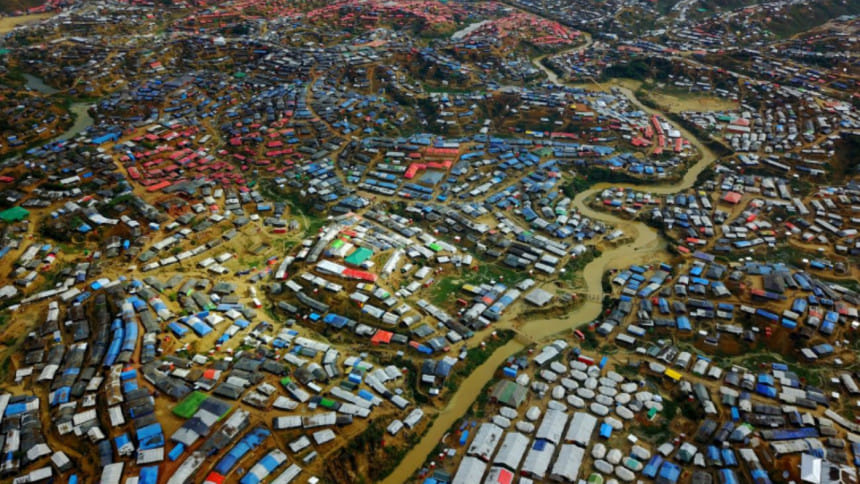

The Rohingya crisis as it is unfolding gradually has many faces that should be of concern to the Bangladeshi people and the government. In July 2017, prior to influx of the Rohingya refugees, the combined estimated population of Teknaf and Ukhiya was slightly over four lakh. The sudden gush of an additional eight lakh Myanmar refugees by December 2017 was overwhelming. The numbers keep rising even today. The presence of this massive number of refugees has impacted on everyday carrying capacity of the region; today, this is felt on all aspects of life and cultures—both for the hosts and refugees themselves.

An immediate impact was on land and local resources—for instance, the massive loss of forests and changes in land use from forest/agriculture to housing and camp sites for resettlement of the refugees. In addition, many reported on the growing social, economic, environmental and health impacts of Rohingya refugee resettlement. The unplanned and makeshift settlements at the early stage of the surge on hill slopes and forestlands led to vulnerabilities for landslides and other forms of risks and disasters for all.

By July 2018, when I made a short visit to the camp sites, a more orderly system of settlement and camp administration was already established jointly by the Bangladesh government and United Nations High Commission for Refugees through registration, re-grouping and relocation in formally constituted 34 camps, with internal roads, markets, mosques, relief distribution centres, and clinics. Close to 100 national and international NGOs—for instance, Medecins San Frontieres, World Vision, BRAC, Gono Shahthaya Kendro, and others—work as service providers in various fields. In addition, there are literally thousands of aid workers assisting the operations.

The Rohingya crisis, without any doubt, has put a huge pressure on Bangladesh's economy and society. Thanks to the government and international aid agencies supporting the operations, the initial stage of crisis management—for instance, provision for shelter, food, medicine, etc.—helped to cope with the immediate needs. During a meeting in Cox's Bazar, an international refugee resettlement expert—who previously worked in South Sudan, Syria and Jordan—told me that unlike other refugee camps in countries with unstable or weak governments, the Cox's Bazar refugee camps provide "good practice" examples for refugee support and administration" due to a stable system of government and administration in Bangladesh.

Having said this, the flip side of the Rohingya refugee issue is that the repatriation remains elusive at this point, because the environment is not right for repatriation. The Rakhine State has been rocked by successive rounds of violence and extensive military crackdown, following the attacks by Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), the group demanding greater autonomy for Rakhine State. Instead of implementing the repatriation agreement and addressing the root causes of the crisis (e.g., citizenship, freedom of movement, livelihoods), the Myanmar Army has once more escalated their genocidal activities in recent months. On top of this, the Myanmar army now claims presence of ARSA training base inside Bangladesh, which was strongly refuted by the Bangladesh government. The activities of the Myanmar Army, including mobilisation of troops to Rakhine border with Bangladesh, raises a host of security issues and concerns. It appears from reports in Myanmar that the regime will force out the last Rohingya in their fight against terrorism.

Thus, the Rohingya issue has raised many external stakes. The Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) reportedly deployed additional force to patrol the country's 54 km border with Myanmar fearing intrusion through the Naf River and other border areas. The situation seems tense. Amid this, there are also internal security issues such as recent passport forgery cases by some Rohingyas, who were deported by Saudi Arabia. In Cox's Bazar, it is almost common knowledge that many Rohingyas left for Malaysia in the 1990s with Bangladesh passports availed to them through the network of local dalals or agents in collusion with passport officials. Finally, there are also reported cases of Myanmar agents in Cox's Bazar camps and in the country for collecting intelligence data.

Aside from the security issues, there are social dimensions of the emerging issues—for instance, tension between the host communities and the refugee population regarding benefits and livelihood issues due to loss of land and access to forests. The government has taken some measures to quell this, but those may not be enough, because the Rohingya refugees are going to stay longer than initially anticipated. Given zero progress with repatriation and the current attitude of the Myanmar government, Bangladesh should work with the international community to find viable and just solutions to this crisis.

Since an acceptable solution may take many more years, the government in the meantime should undertake a long-term plan for support and sustenance of the refugees and host communities through economic and social development programmes using the resources received from the various development partners and agencies such as the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank and other bilateral organisations. The impact study commissioned by the foreign minister should look into all of the socio-economic and security aspects holistically and help make a long-term plan for refugee resettlement and repatriation options as well.

Mohammad Zaman is an international development consultant and advisory professor, National Research Centre for Resettlement, Hohai University, Nanjing, China. Email: [email protected]

Comments