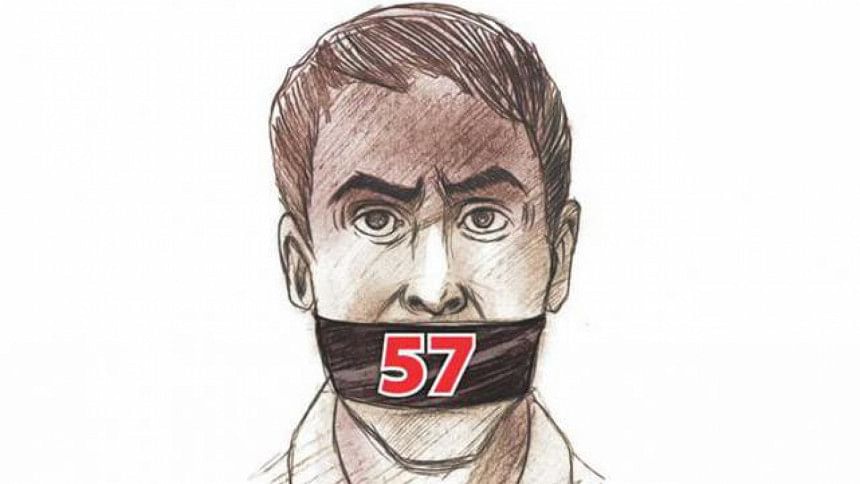

Silencing Dissent

The much-maligned Section 57 of the infamous Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act 2006 has come in handy again for suppressing dissent. This time the target is a well-known professor of law of the University of Dhaka, a reputed columnist and an eloquent speaker.

The freedom-curtailing provisions of the ICT Act have been branded as anti-constitutional by rights activists. Leading jurists have concurred. Even senior functionaries of the state have publicly expressed concern about its widespread abuse. In the face of demands for scrapping of the law from different quarters—journalists, rights activists and social media activists—the commitments from the state authorities ranged from addressing the gaps that have created conditions for its abuse to removing Section 57 in its entirety. Thus there is a general consensus that something is grossly wrong with the particular provision of the law. It is in this context that the law professor has become the latest victim of its misapplication.

The available statistics from the Cyber Tribunal sources inform that so far about 300 cases have been initiated under Section 57 in the first seven months of this year alone. Over two dozen journalists have been sued and several arrested. The filing of a high number of cases under the section prompted the Inspector General of Police to advise all police stations to secure clearance from the legal wing at the Police Headquarters before registering any case under the section. Newspapers, citing sources at the Cyber Tribunal, further inform that among the cases filed under the ICT Act, about 90 percent were recorded under Section 57 and a large number of the plaintiffs were from the ruling Awami League.

This piece attempts to capture the sequence of events surrounding the episode. It argues that the so-called aggrieved parties connected with the ruling party have sued the professor with the ulterior motive to harass him for his dissenting views and the state agencies appear to have become complicit in pursuing that agenda.

It all began when a defamation case was filed by the cousin of a state minister who is also the member of Madaripur District Council against Professor Asif Nazrul on November 23 for an alleged Facebook post. The complainant alleged that the accused "willingly tarnished the image of the minister socially and politically by uploading the post." The professor was ordered to appear before the district court on December 14. In a separate move the nephew of the said minister filed a complaint against the professor under Section 57 of the ICT Act for the same post over alleged irregularities in recruitment in Chittagong port. As per the procedure, the complaint was forwarded to the police headquarters in Dhaka for clearance. The approval came in no time, on November 26. Earlier at a TV talk show the junior minister had threatened the professor of consequences.

The cases were lodged despite the law professor's virulent and persistent denial that he was not responsible for the post. Furnishing impeccable evidence, he claimed people running fake pages purporting his name were responsible for the misdeed. He noted that he had already cautioned all about the existence of those fake pages by posting a status on his own Facebook account and the fan page that he administered. He urged the authorities concerned to verify the authenticity of the culprit Facebook page before pressing charges against him.

Anticipating trouble the professor applied and secured anticipatory bail from the high court on November 28. He did so as he apprehended that even before he is able to prove his innocence in court he "could be arrested anytime and get locked up for an indefinite period." He claimed that the law was being used against him only to cause harassment and suffering to him and his family. Justifiably, the professor noted that people behind the fake pages and those who filed false cases should be punished instead. Nazrul called upon the law minister to repeal Section 57 of the ICT Act immediately to save the innocents from the "wrath of the powerful."

In another twist to the bizarre tale, on December 4, the government lodged an appeal against the high court order that granted ad-interim anticipatory bail. The attorney general pleaded the government case before the appellate division chamber judge. The matter was adjourned for a week.

The Asif Nazrul episode raises some interesting questions.

Firstly, the actions of the aggrieved relatives are somewhat understandable. After all, a senior and the powerful (at least for now) member of their clan were mocked in public and they felt it is within their rights to seek redress from appropriate authorities. What is mysterious is the engagement and enthusiasm of the state agencies.

Some questions arise.

First, on what considerations have these frivolous cases merited acceptance by the authorities?

Second, when its clearance was solicited from the legal department, what were the grounds for the Police Headquarters in Dhaka to give a green light to these spurious cases? After all, the accused vociferously denied any wrongdoing and was making persistent demands for instituting enquiry against what he claimed to be fake Facebook accounts that operate under his name. Perhaps there is a case for the police authorities to explain what prompted the agency to rely on the contents of the fake Facebook accounts instead of the genuine Facebook account of the law professor. It is interesting to note that police authorities moved super fast and took only one working day to grant the clearance as the period of November 23–26 was interceded by weekly holidays.

Third, was the case so important for the state that the right of any accused to secure bail had to be challenged and that too, by the highest law officer of the land, the attorney general? One is at a loss to understand how a defamation case against an individual can be an issue of state priority. It may be noted that the challenge was mounted at a time when the draconian non-bailable provision of the ICT law is being widely condemned. In the absence of any other tangible evidence of wrongdoing, shouldn't the professor's professional standing constitute sufficient ground to grant him bail?

Finally, why could not the concerned arm of enforcement of digital security apparatus still trace the origin of the account that has caused so much hullaballoo? Is this the result of their institutional inefficiency or is this also otherwise motivated? After all, perception is rife that surveillance capacity of the state has been greatly enhanced over the last several years, thanks to millions of hard-earned dollars being spent.

It is also curious that "aggrieved relatives" of the state minister identified the professor as the perpetrator of harm to the reputation of the illustrious member of their family. This is notwithstanding the fact that charges of nepotism in the selection of the port personnel were originally levelled by a member of the ruling coalition on the floor of the parliament. This was widely reported and covered in the print and electronic media. If the aggrieved relatives were genuinely concerned about seeking redress, why have not they brought charges against those individuals and entities that were the original sources of the perceived harm? The concerned minister also appears to be silent on the question as the dissident professor remains the obvious target.

This episode is a blatant manifestation of how members of the ruling party abuse draconian laws against those who do not toe the official line and are not in cahoots with the party in power. It also lays bare the ways in which the state agencies have been made subservient to the ruling regime. All these do not bode well for a polity that has paid such a heavy price for independence and the establishment of democracy.

CR Abrar teaches international relations at the University of Dhaka.

Comments