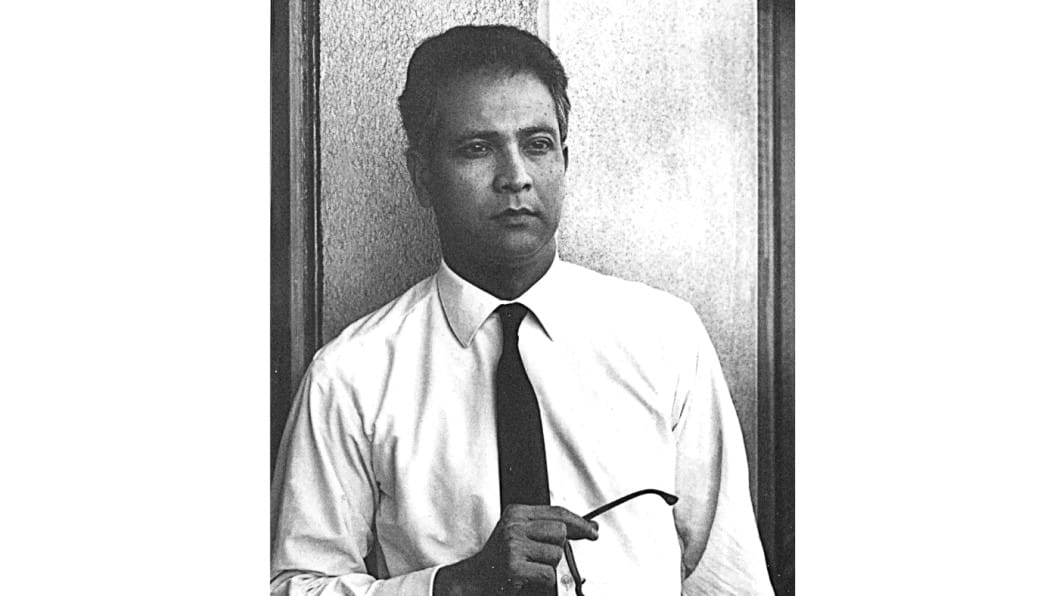

Syed Waliullah in Paris

It is well-known that Bangla literature took a new turn in the 1940s. Following the revolutionary work of Kazi Nazrul Islam, we got four powerful poets among Bangalee Muslims: Farrukh Ahmad, Abul Hossain, Ahsan Habib, and Syed Ali Ahsan. At the same time, we found three extraordinary novelists and short story writers: Shawkat Osman, Syed Waliullah, and Shamsuddin Abul Kalam.

Here, we are going to focus on Syed Waliullah, who wrote short stories that were admired by many. He established a publishing concern – Comrade Publishers – to publish three noteworthy books: The Indian Musalmans by Sir WW Hunter, Momener Jobanbondi by Mahbubul Alam, and Ratrishesh by Ahsan Habib. He also edited two series.

This was his Calcutta period before joining The Statesman as an assistant editor. After Partition, he had several positions in the press, in Dhaka, Karachi, Delhi, and other places in South Asia. Finally, after he was posted in Bonn, West Germany in December 1959, he once visited Paris on official business when I, a new comer, had the opportunity to meet him briefly for the first time. We had quite a hearty discussion as we both are Chittagonians. However, I was dismayed when he told me that he understood the dialect, but could not speak it. He never stayed for long in Chittagong, and at home they rather preferred to speak in chaste Bangla. Incidentally, I must express that I was acquainted with his name and a few of his short stories in 1948, when I became a yearly subscriber of the monthly Saogat from Calcutta.

Syed Waliullah wrote about 50 short stories. Some of the stories he originally wrote in English, and some others he translated to English himself. We quote the first few lines of his story "The Escape" published in The New Values (Dhaka, Vol. 4, 1952):

"This was the moment of chaotic indecision punctuated with the incredibly real and decisive rattle of the slow moving train over the rusty metre-gauge rails which stretched and continuously narrowed behind. The sun rode high mercilessly in the cloudless sky. The tedious journey under its vast expanse of void and heat seemed without any destination. Human odour hung heavy in the crowded compartment; a little, insignificant fly buzzed near the toilet door; a thin line of dirty water streaked along its threshold.

"The young man felt restless." (Pg. 26)

His story "This Life," published in the PEN collection Under the Green Canopy, begins like this:

"The fearful days passed! Not a wisp of cloud, grey or white, water-laden or smoke – black was to be seen anywhere within the line that bounds man's sight. The sky, load-like, dull and vast in emptiness, gave one sometimes a very queer feeling. It appeared to be burning itself out in a mysterious, invisible way melting into nothingness a void that was abstract and dead; hence incompatible with the present, and one's hopes and despair." (Pg. 157)

In his lifetime, Syed Waliullah published only two books of stories: the first one, Nayanchara, was published by the famous Purbasha (Calcutta) in 1946, and the second one, Dui Teer, was published by Naoroz (Dhaka) when he was in Paris in 1965. I used to use it as a textbook for my students of Bangla, including his wife Anne-Marie. In it was his famous story "Ekti Tulshigachher Kahini." The pathetic separation of Hindu-Muslim culture is retold in this story with deep insight. The story "Nayanchara" tells us the sad tale of Ponchasher Monwontor – i.e. the famine of 1942-43 (1350 in Bangla calendar).

From Paris, he sent to Bangla Academy the drama Surongo (underground passage) for publication. Later, he composed the well-known Bohipir (a spiritual leader who speaks in the language of a book). Another piece, Torongobhango, created sensation among the theatre-loving people. The short play Ujane Mrityu (Death in the upstream) from 1964 is also quite remarkable. During this period, Waliullah once expressed to me that on his return home and staying there for some time, he would like to write a new drama with the experience gained thereby. It may be noted that during this period – the 60s – a lot of experiments happened in Europe and the world outside in connection with dramatic creations.

However, Syed Waliullah was mainly concerned with his ideas of a new novel. After Lalsalu in 1948, he finally started writing Chander Omaboshya (The Eclipse of the Moon). He even thanked me as he took the title from a book of mine. This was indeed a new experience in reading this short novel. All the characters are very clear and well depicted. Waliullah wrote this book in a village near the Alpes during a few weeks of holiday. What VS Naipaul quotes from Albert Camus' The Rebel, "The novel is born at the same time as the spirit of rebellion and expresses, on the aesthetic plane, the same ambition," appears to be justified.

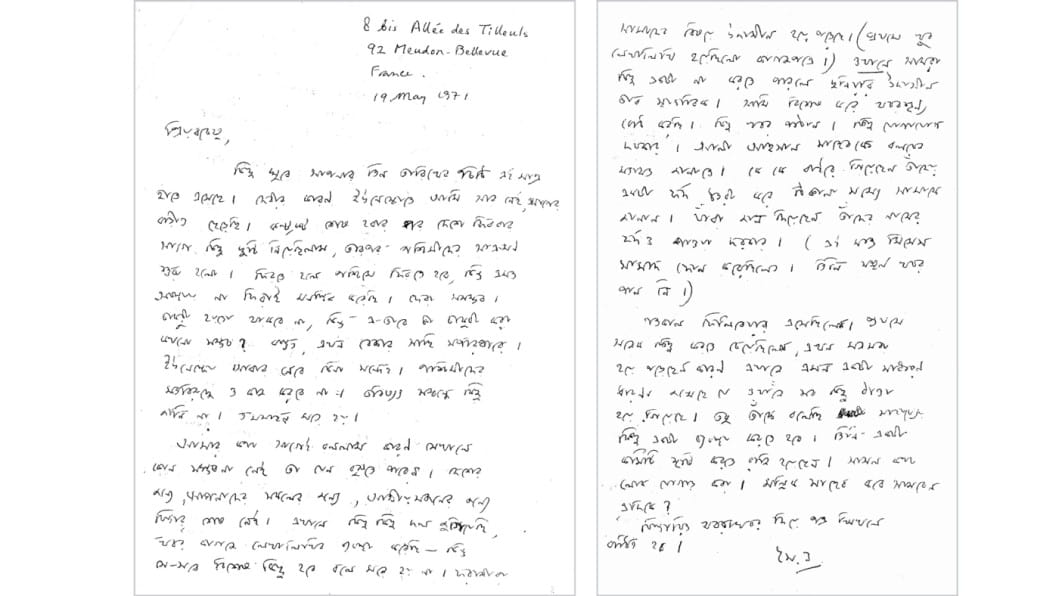

Later, Waliullah even remained quite ambitious when he wrote his last novel, Kando Nodi Kando (1968). One afternoon at Unesco, he explained it to me. It was the time when I was returning home after closing my chapter of staying abroad (August 1968). Later, I met him in Chittagong in 1969 and we discussed much about his dramas. He insisted on his stay at home for some time; he even purchased a house in Gulshan. However, eventually he returned to Paris. Unfortunately, he lost his Unesco job, and we started our freedom struggle. In reply to my letter, he wrote in two pages explaining the situation in Paris (May 19, 1971).

So far, we have discussed about Waliullah's literary life. But what was his official duties in Paris? As I was allowed to use his office at least once a month to read newspapers from home and to discuss French political and cultural matters, I could also look into his works. First of all, he had to reply to inquiries from different quarters about our country. He used to organise press conferences, throw lunch parties – I knew of one such lunch party where he invited Professor Syed Ali Ahsan on a visit to Paris, and Madam Rajeshwari Datta, famous Rabindra Sangeet singer and wife of his former senior colleague and poet Sudhindranath Datta from his Statesman days in Calcutta. During this decade, I might have dined with them at least five times at his residence.

He had to publish a bimonthly newsletter in French. He occasionally wrote articles on different subjects. He also had to organise some seminars, one of which was on poet Iqbal. Six renowned intellectuals presented papers, which were published in a booklet. Waliullah designed the cover.

Besides, he had to look after the dignitaries visiting from home. Sometimes, there were problems with students and trainees in the technical fields. I helped him with two cases of Ebne Golam Samad and (artist) Rashid Chowdhury. I still remember the discussions we had during the embassy receptions. Waliullah and his wife Anne-Marie Thibaud were extremely humble and hospitable.

In 1961, shortly after he joined the Paris office, he invited us for a lunch cooked by himself. Later, I was especially asked to join a French anthropologist, who had returned after spending six months in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. I acquired his book. His wife, a teacher of Burmese, was a colleague of mine.

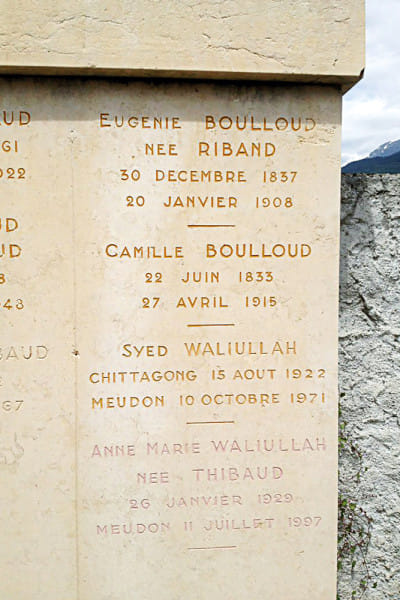

I remember meeting Waliullah after he came to Paris with his wife and three-year-old daughter Yasmine (Simine). Later, he had a son, Iraj. I met them several times later on. They were very careful about the heritage of their father. Last time, in 2018, I visited Cimetière de Vaulnaveys-le-Haut with their aunt Françoise and found the grave where Waliullah and Anne-Maria lie together.

In the summer of 1968, there was a student revolution in Paris. Rashid Chowdhury returned with lot of encouraging news from home. At the residence of Syed Najmuddin Hashim, we discussed much about the future of Bangladesh. Even an intellectual movement like Na! (No!) was not spared.

From January 1965, I grew even closer to Waliullah as I was appointed as a lecturer at the School of Oriental Languages in the University of Paris. Mrs Waliullah got herself admitted as a student. Waliullah tried his best to help us build the department - he especially brought books from Dhaka for the school. After joining Unesco, he handed me a few articles to write for an encyclopaedia proposal of the famous Larousse publications. The articles were published in 1971.

I very much remember the time I spent with him when I drove him alone from the reception of Chittagong University to the town. He was pleased to have known that even a waiter of a restaurant had read his novel Lalsalu.

There are so many memories! I remember him not only as a great writer, but also as a man of extraordinary human qualities. For many years, I had recapitulated these memories with Anne-Marie, Syed Ali Ahsan, and others. Sophisticated to the highest degree, Syed Waliullah always remained alerted to use common sense. He would be well-dressed, well-mannered, and extremely friendly to all his friends.

Dr Mahmud Shah Qureshi is an eminent Bangladeshi scholar. He has been honoured with numerous accolades, including Ekushey Padak and France's Légion d'honneur.

Photo courtesy: Simine and Iraj Waliullah

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments