'Why don't RMG owners pressurise buyers instead of workers?'

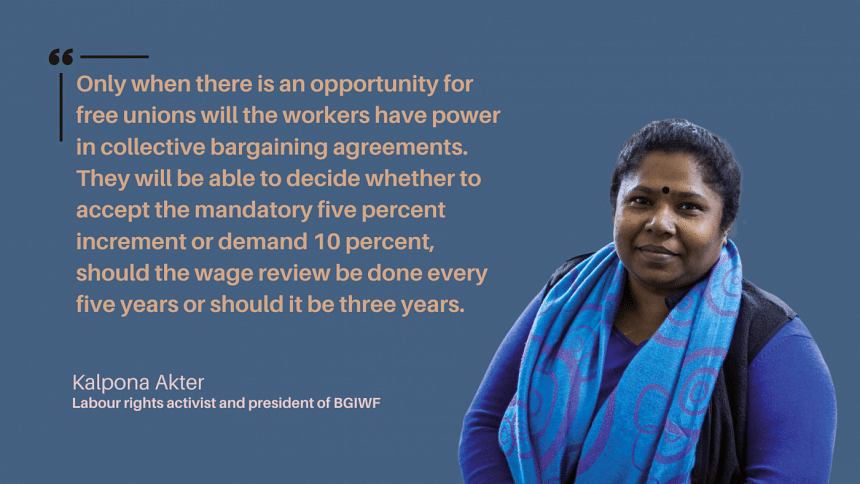

Kalpona Akter, a labour rights activist and president of Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation, discusses the ongoing protest of garment workers, their circumstances, and demands for a liveable minimum wage in an exclusive interview with Naimul Alam Alvi of The Daily Star.

Can you contextualise the latest protests by garment factory workers in Bangladesh?

The minimum wage for ready-made garment factory workers was last reviewed in 2018, when workers demanded Tk 16,000 of monthly wage. The government and RMG factory owners settled on Tk 8,000; since then, the workers have received a mandatory five percent wage increment. Even with the increment, entry-level workers currently earn only around Tk 9,000 per month.

Since 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have triggered a worldwide cost-of-living crisis, impacting everyone, including the RMG workers. Regardless of their wage level, workers are struggling to make ends meet, unable to afford basic necessities for themselves and their families.

Despite the five-year minimum wage review cycle, there seems to be no preparation on the factory owners' end. Their proposal should have come earlier, but instead, they belatedly offered a disrespectful proposal in late October to set the minimum wage at Tk 10,400—not even half of the workers' demand. This angered the workers, whose demand is now clear: either reduce essential commodity prices or increase wages.

But the workers' voices are being suppressed. They are being beaten by law enforcement members and goons, fired at indiscriminately, and subjected to lawsuits. Some have been arrested, creating a climate of fear among workers and labour rights activists alike.

The owners accuse the workers of conspiracy, but how is it a conspiracy when eggs cost Tk 15 apiece, onions Tk 120 per kg, and potatoes Tk 70 per kg?

How long can the police suppress the workers? The owners may not be able to "afford" Tk 23,000, but the wage certainly cannot be Tk 10,400 or even Tk 12,000. It must enable the workers to survive, buy food, pay rent, and support their families. With stagnant wages, reduced capacity to meet basic needs, and no significant growth between entry-level and skilled workers, how long will the workers suffer in silence?

Factory owners argue that they are unable to increase minimum wages or overall wages due to competitive market pressure and the need to maintain low prices. What's your perspective on that?

The factory owners claim they must produce low-cost products due to buyers' low prices. They create a competitive environment both internationally and domestically. However, Bangladesh is the world's second-largest apparel producer. If we still cannot strengthen our position and negotiate with our buyers, establishing a minimum price below which we will not go, it's disheartening. We have powerful organisations like the BGMEA and BKMEA. What do they do? Why do they foster internal competition within our sector? What is the purpose of their association then? As long as they don't learn to say no, they'll keep producing cheap clothing and claiming no profit. Yet, we see many of them expanding their businesses and building new factories. If they don't have the money, I'm at a loss as to how they find the funding to build these factories.

Why do you think factory owners redirect pressure from buyers onto workers when such demands arise, offering excuses that the buyers will not listen, rather than negotiating for better prices and subsequently better wages for the workers?

Because they can get away with putting pressure on the workers. Factory owners have embedded themselves within the government. If the legislators are the factory owners themselves, where can I go to seek justice? Where is the impartial body that will listen to the workers? The government is not neutral. A high percentage of MPs are garment factory owners. They are concerned about themselves, not the workers. Their "power" works to silence the workers, labour rights activists, and those who are part of unions. Their strategy does not include negotiating with the buyers.

They should have met with the buyers back in 2022. They should have informed them that the workers' wages in Bangladesh would need to be increased the following year, and set a minimum price limit that the buyers must adhere to. Instead, whenever there has been a movement to raise wages, the workers have been suppressed. Cases have been filed against the protesting workers; they have been fired from their jobs, and they have been blacklisted. The factory owners have managed to do this because they have the muscle, money and administrative power, none of which the workers possess.

However, there is hope for a solution. Many of the sourcing countries are working on laws for human rights due diligence. Germany, France and the Netherlands have already enacted them, and the European Union is also going to adopt one. One of the elements of such laws is to ensure a living wage for workers. We are trying to ensure that the question of living wage covers contributing countries, so that sourcing countries cannot shake off their responsibility by saying the manufacturing countries will ensure the living wage of the workers. We are saying that no, the companies that are sourcing from manufacturing countries have to make sure that they are paying enough and that the money contributes to the living wages.

Another hope will emerge if the power is neutralised here. And to do that, you have to give the opportunity to form free unions in the factories. Only when there is an opportunity for free unions will the workers have power in collective bargaining agreements. They will be able to decide whether to accept the mandatory five percent increment or demand 10 percent, should the wage review be done every five years or should it be three years.

We see RMG workers frequently taking to the streets to demand wage increases and other improvements. Why does this have to happen so often?

The legal framework exists. The law clearly states that the owner, worker or the government can review the wage structure after three years if the inflation rate is high. It is only mandatory after five years. Workers should not need to take to the streets. The procedure should involve a wage board meeting every five years. Both parties will submit proposals, there will be discussions, and the wage will be announced.

I spoke with labour rights activists in Kerala, India; they were surprised to learn that our minimum wage review occurs every five years. They do it annually there, and workers don't have to take to the streets for it. Wage review is the owners' responsibility. They announce a wage that aligns with the inflation rate. If our neighbouring country can do it, why can't we? Why wait five years; why not review the wage every year?

Repression can never silence workers' voices or labour movements. It needs to be addressed systematically. We need to have discussions and provide workers with a platform for dialogue, such as a trade union. The second step is to move beyond the profit paradigm. If we don't include workers in profit-sharing, this backlash will continue. Calling the workers a part of the owners' families is a mere lip service if we don't believe it wholeheartedly and don't demonstrate it in our actions.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments