Mega projects, mega dreams: But where is that omelette the government promised us?

In a 2014 article on sterile policy measures of European technocrats, Slavoj Žižek cites the example of Romanian leftist writer Panait Istrati who visited the Soviet Union in the 1930s. It was a time of big purges and show trials. So a Soviet apologist, trying to convince Istrati of the need for violence against the enemies of the state, evoked the proverb, "You can't make an omelette without breaking eggs." To which the latter tersely replied, "All right. I can see the broken eggs. Where's this omelette of yours?"

The same can perhaps be said, mutatis mutandis, of the drive for development in present-day Bangladesh. For years, big government projects and initiatives were packaged under that umbrella term with a promise to end the country's perennial poverty. Citizens were assured that there would be food at affordable prices, jobs in every household, proper housing, schooling, and healthcare. That their rights would be protected, their safety guaranteed, and their mobility unrestrained. In return, all they have to do is have faith and wait. But seeing how long that waiting period has been, citizens may well ask: Okay, but where is that omelette that the government keeps promising us?

The omelette and broken eggs are apt metaphors for the ever-widening gulf between the promise of development and the reality. The omelette, or as you may like to call it "Shonar Bangla," is the glue that has held a disgruntled nation together. For 50 years and counting, it gave politicians the equivalent of the American Dream to entice citizens with a future that would be transformative—not just for the nation in general, but at the individual level as well. After all, what is development if its fruits are not enjoyed by all intended beneficiaries? The broken eggs, the price to be paid for the proverbial omelette, give them a sobering reality check.

The pitfall of measuring development based on macrodata is that it shows the big picture but fails to account for the development achieved, if at all, on a micro/personal level. There is no scope for taking stock of the lived experience of individuals. One of the reasons for having public representatives in the policy circles is that they can offer insights that technocrats sitting in their armchairs cannot. But if the lived experiences are any indication, both groups have miserably failed to recognise or offer any solution to the continued sufferings of ordinary people.

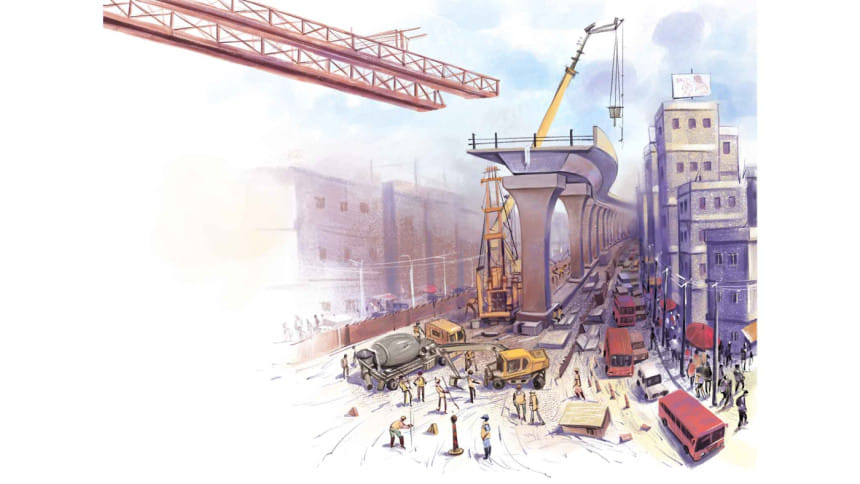

Just think of all the road and transport related projects taken up over the last decade or so. Have we experienced increased mobility during this time? Have our roads become safer? Do women and girls feel more secure? Does any of us? Despite all the money that has been spent during this period, the daily traffic hasn't thinned out, nor has it become more manageable. Out in the highways, the mobility has increased somewhat, but at the cost of commuters being more at risk than ever before. The state of air and sound pollutions—due in large part to mismanagement and irresponsible behaviour in the transport sector—has deteriorated to a point where Dhaka is cited as a cautionary tale for botched urban planning.

As I write this, a national daily reports that the price of rice has increased again, despite the high yield of Boro rice. We're repeatedly told how Bangladesh has become self-sufficient in food production. On the other and more relatable side of this picture is how food is becoming more inaccessible by the day. How do you reconcile these contrasting scenarios? The prices of all food and non-food items have skyrocketed beyond comprehension, even though ordinary citizens' capacity to purchase hasn't risen concurrently. More people today are living in semi-starvation. The sad part is, this is never reflected in any official statistics. The robust economic growth figures shown by the government are thus either designedly selective or manipulated to cover the gaping hole underneath our feet.

True, our economy has grown in size and scope, but so has public spending on ill-planned and ill-executed projects. Unnecessary construction projects are being taken up to fill the coffers of groups with vested interests, even before the scars of old projects are healed. Amid ongoing concerns about a currency crisis, there seems to have been a realisation in the policy circles about the importance of tightening our purse strings from austerity measures, leading to the cancellation of foreign trips of public officials and postponement of projects requiring imports. But the drive wasn't born out of a genuine desire to cut all unnecessary expenses of the government, which would have required fixing internal, systemic challenges that are draining public coffers across the administrative spectrum. Today, public projects and initiatives are essentially money guzzlers—thanks to corruption, mismanagement and lack of coordination. They exist to serve the interests of the politico-bureaucratic complex. Citizen welfare makes for good lip service only.

The situation in law enforcement, education, health, environmental and other sectors is no less dystopian. Many had hoped that the end of Covid-19 would usher in Vivid-22, but the pandemic has laid bare—for all to see and panic while doing so—how fundamentally flawed these sectors have been all along, nipping in the bud any lingering romanticism about the pre-Covid time. The pain and sufferings that are being caused on a daily basis are bound to disillusion anyone.

I can rattle off a long list of problems dogging each public sector from newspaper reports alone. These will show how the lived experience of the majoirty hasn't reflected the rosy picture drawn of the country's development. It's getting increasingly harder to navigate the chaos, insanity and unending suffering on the streets and markets, in the employment and service sectors, in educational institutions, and in virtual space. The question is: How long will we have to bear with the encumbrances of development before we see a truly transformative future?

Badiuzzaman Bay is an assistant editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments