The ‘crazily courageous’ world of a Tagore devotee

A small, upmarket café housed in what may seem to be a refitted basement is the setting for my interview with Martin Kämpchen, the German author, Tagore translator and journalist. The location couldn't be more symbolic. Here we are, in the heart of one of Dhaka's most bustling neighbourhoods, sitting in a restaurant that offers an "exceptional gastronomic experience", with small groups of diners strewn around, as a cacophony of music and voices fills the room. These visual, auditory and even culinary distractions have little effect on Kämpchen, who bears himself like one who has made his peace with the world. This sangfroid amid the noise, in a way, symbolises the conviction with which he has researched, translated, written on, promoted, and basically "lived" the life and work of Rabindranath Tagore for the better part of his life.

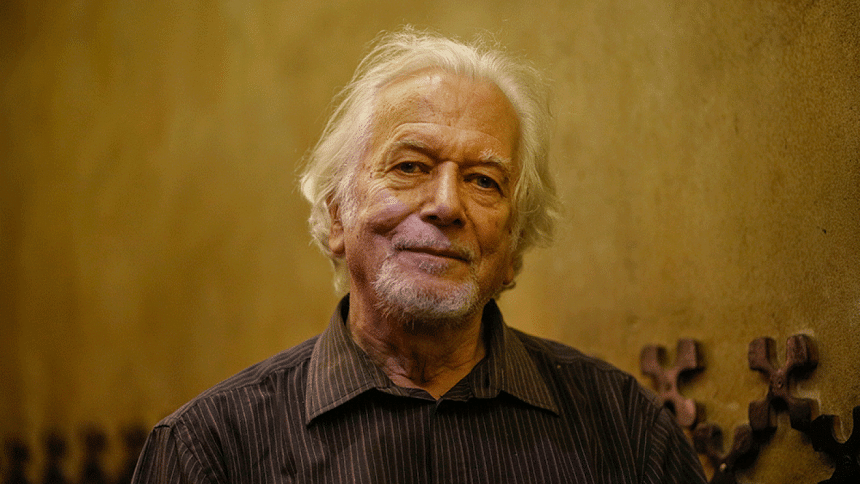

As we meet for the interview in late October, Martin Kämpchen (he allows me to call him Martin Da) comes across as the archetypal gentleman-hermit, with his slouchy wardrobe of checked shirt and loose-fitting trousers, his white goatee, a nondescript messenger bag hung off one shoulder, and his warm, ready smile. He speaks softly, so much so that I have to strain my ears to hear him. He is fluent in Bangla and English, effortlessly alternating between the two. He speaks in short, measured sentences, a trait that he perhaps developed during his career as a journalist.

Born on December 9, 1948 at the municipality of Boppard, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, Martin Kämpchen is perhaps the most well-regarded contemporary German scholar on Tagore. He has written extensively about Tagore, published several books of translations of poetry, toured different parts of the world to give lectures, held poetry readings, gave interviews, etc. As a writer, he also navigated through a myriad of other themes and genres, and wrote about many literary and cultural figures including Sri Ramakrishna (his second PhD thesis was about a comparative study of Ramakrishna and Italian saint Francis of Assisi) and his chief disciple Swami Vivekananda. He published short stories and diaries based on his travels. As a journalist, since 1995, he has been writing for the German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. In his columns, he writes about the Indian culture and society and sometimes about Bangladesh, too.

But it is his single-minded devotion to Tagore that stands tall in the hall of his life's pursuits. Kämpchen is himself the living embodiment of what he calls "Rabi Premi" (Tagore-lover), insofar as one is able to embody an ideal. It's a term that, he says, comes with a responsibility. "For some people, loving Tagore means only singing his songs, reading his books, reciting his poems, doing his plays. They don't care for the poor, the disadvantaged, like Tagore did. I don't think they're a true Rabi Premi," he tells me. I show him a copy of a feature story published by The Indian Express in 2012, titled "The German Tagore", in which Kämpchen expounded his theory of the socially engaged Rabi Premi by saying, "Tagore's ideal is that men, irrespective of nationality, work together and achieve a common goal." I draw his attention to the heading. He laughs at it, rejecting it as a hyperbole. But the story behind this story remains a testament to his enduring belief in socially responsible scholarship which he has put into practice in his adopted hometown in West Bengal, India.

The story traces his activism in the twin villages of Ghosaldanga and Bishnubati, on the outskirts of Santiniketan. Kämpchen has been working with the villagers, mostly members of the Santal community, ever since he started living at Santiniketan's Purba Palli nearly four decades ago. He helped build schools, roads and toilets, implemented afforestation and fishery programmes, and sponsored the education of poor children, among other development initiatives. He has been so immersed in their life that "were it not for his Caucasian appearance and his accented Bangla, he could be mistaken for a Santal." These days, he is not directly involved with overseeing the activities, but remains engaged, regularly cycling to the villages from his abode. He occasionally visits Europe, but never staying away for too long.

I ask him about his most memorable experience in Bangladesh, a country he visited many times. He says it was in 2007, when he came with a group of Santal boys and girls as part of an initiative by the Goethe-Institut Bangladesh. "We met with Santals in Bangladesh. So there was a joint performance of dance and songs. It was quite a revelation for us when we learned that the Santals of West Bengal and the Santals of Bangladesh had exactly the same culture. Within a few minutes, they were able to fall in step and sing the same song and do the same dance routine. Never before had I realised that there could be such a bond between communities from different countries."

At this point, our discussion reverts to the topic of his work, his work in translation in particular. How difficult is it to translate Tagore?

"It has been quite courageous, maybe crazily courageous, of me to try to translate Tagore's poetry from Bangla into German. It has to be understood that Tagore didn't really translate his poetry from Bangla into English. It was rather a paraphrase—lyrical prose—an approximation of the content, not the words. Even then, he received a Nobel prize for that—which, in my view, was dangerous because then he continued translating. These poetic products in translation were quite inferior to his original Bangla poetry. And these translations were later picked up by European publishers who translated them into their own languages, without realising that the originals were not in English. The inferior quality of these translations is partly the reason why he is not widely read outside Bengal and Bangladesh. It disturbed me. So I decided to translate his poetry directly from the source language."

He also talks about his own method of translation. The challenge, clearly, is to preserve the authenticity of the source material and at the same time accurately capture the nuances specific to the Bangla language and culture. "I was aware of the many difficulties that exist in translating poetry from Bangla into German," he says. "So in my translations, I gave footnotes and commentaries, line-by-line commentaries, to bring the reader closer to the original. This is a rather unconventional way of translating poetry, because poetry should be just turned into poetry, right? But I saw it as a necessary compromise and the success of my books shows that it has worked well with the public." So far, Martin Kämpchen has published some ten books of translations and anthologies. His first, a collection of one hundred poems from Tagore's Sphulinga, Lekhan and Kanika. It was followed by a selection of 50 poems. The third volume contains mostly translations from Gitanjali and Shishu.

I ask him if Rabindranath Tagore will survive in today's fast-changing literary landscape where the superficiality of "chick-lit" and thrillers, for instance, is taking over the profundity of serious literature. Kämpchen is a believer, and a rational one at that. He says: "Serious literature or art has always had a difficult time to make itself known and appreciated in society. It happened before, and it is happening now. This is also the case with Tagore. There are, however, four aspects that I think will keep him relevant.

"First, Tagore professed what I call an 'eco-spirituality' which sits well with the global call for a reversal of the ongoing destructive tendency of human beings to compromise nature, causing rapid climate change. In his poetry, novels and essays, Tagore described the sacredness of nature. He urged us to respect it. This message is absolutely critical to our survival in the future.

"Second, think of our current education system, both in India and Bangladesh, which is mainly focused on rote learning. This is a totally uncreative and rather inhuman way of learning and absorbing knowledge. Tagore offers a different, rather joyful approach to education where the teacher is not simply a giver of knowledge but also, more importantly, a model for their students. His idea of education inspires creativity as it involves learning through fun, through theatre, art, dance, etc. Third, Tagore will stay relevant because of his message of social service and commitment. And fourth, his idea of universalism. Today, as you know, various countries in Asia and Europe are plagued by the waves of nationalism and nativism. Tagore is a strong voice against such narrowmindedness. His thoughts on these issues should be read and re-read."

Badiuzzaman Bay is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments