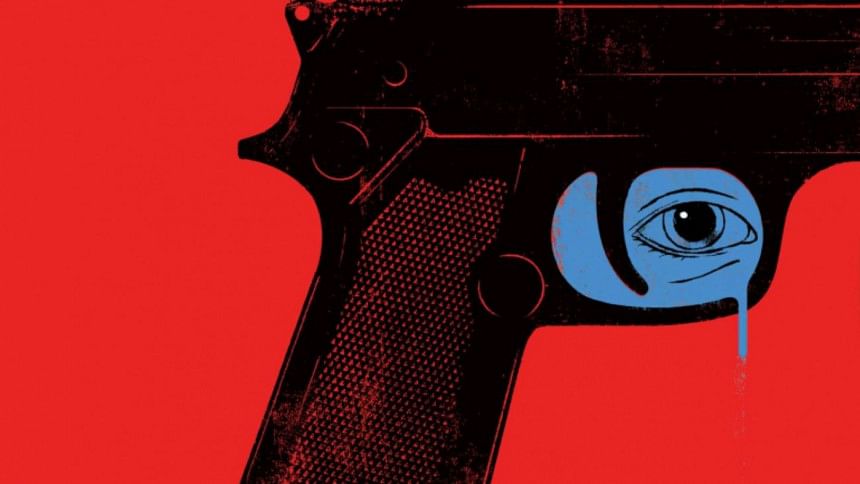

Vigilante justice or what?

On January 17, police in Khagan, Savar recovered the bullet-hit body of a man who was later identified as Ripon. Ripon, a line chief at a local garment factory, was the prime accused in a gang-rape case involving a female worker from his factory. There was a note attached around his neck, which read: "I'm the main culprit behind the rape."

Nine days later, roughly a hundred miles south of Khagan, in a village called Baltala in Jhalakathi, another bullet-ridden body of a rape suspect was found. This body, too, carried a note which read: "My name is Shajal. I am the rapist of [the victim's name]. This is my punishment."

Both the cases have attracted much attention on social media. That ordinary people would welcome and condone what appears to be an instance of "vigilante justice" is hardly surprising—especially in a country where the legal system has not been able to evoke public confidence.

In a recent interview with BBC Bangla, Nur Khan Liton, a rights activist and crime analyst, says he believes the recent murders might have been committed by the law-enforcing agencies, citing previous precedents of them being involved in extrajudicial killings.

In April and May last year, two suspects in child rape cases were killed in alleged shootouts with police in Cox's Bazar and Satkhira, respectively. In 2014, a suspect in a case related to the abduction and rape of a college student was also killed in an alleged shootout with police detectives in Uttara.

Liton's assumption about the involvement of security forces in the deaths of alleged rapists was reinforced, most recently, by yet another incident on January 28, roughly a day after his interview was published. The online news outlet, bdnews24.com, reported that a rape suspect was killed in Chattogram—this time, by police's own admission, in a "shootout".

Indeed, not every ordinary citizen would dwell on the issue so deeply and critically. Therefore, to many people, as indicated by their comments on news reports shared online, the murders of rape suspects bear hallmarks of "divine justice" delivered by some mysterious saviours.

To some others, even if the security forces were involved in the killing of suspected rapists, it didn't matter. Whenever rape incidents take place, some people take to Facebook calling for justice through extrajudicial means. "Take the rapists to arms recovery operations"—one Facebook user said after the news of a rape incident emerged recently, alluding to the reason sometimes cited by law enforcement agencies to defend the killing of a suspected criminal who, they claim, died in a shootout during a so-called arms recovery operation.

Such a public attitude towards the murders of suspected rapists partly stems from the horrendous nature of the crime in question, and partly because the people are tired of seeing alleged rapists go scot-free and exploit loopholes in the justice system. According to a 2017 report based on police data, the percentage of rape cases that ended in conviction over the previous five years in Bangladesh was less than two percent.

What the proponents of vigilante justice do not realise, however, is the danger of executing a suspect without a fair trial. How can we compensate a suspect killed extra-judicially, if we later find out that he wasn't actually involved in the alleged crime? Have we not heard of the legal maxim "It is better that 10 guilty persons escape than one innocent man suffer"? Without a fair trial, how would one determine whether the suspect was deserving of capital punishment? Apart from the fact that such executions constitute flagrant violations of human rights, there are other issues too.

One may recall the early days of Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) when many of its operations were enthusiastically supported by the majority of the people. RAB proved to be extremely ruthless and efficient in hunting down criminals, militants and extremists alike. "RAB is easily the [Bangladesh government's] most popular initiative in its three years in office," observed Harry K Thomas Jr, the then US ambassador to Bangladesh, in January 2005, in a diplomatic cable later revealed by the Wikileaks.

However, as soon as independent media outlets began to question the RAB's "crossfire" narrative and exposed grim details of its extrajudicial killings—especially that of the Narayanganj seven-murder incident—the public grew suspicious and eventually became disillusioned with the fantasy of having a force that would keep them safe and summarily execute "criminals" bypassing the prolonged judicial process.

The public today is certainly more aware of the dangers of allowing the agencies to operate with carte blanche. Maybe that is why the "anti-drug war" launched last year, in which hundreds of alleged drug traders were killed, garnered divided support from the people. Their scepticism derived not only from their previous experiences but also from the fact that the operation was launched during an election year—and many innocent people including some opposition activists were allegedly victimised in the process, as reported by independent media outlets.

Yet, when alleged rapists were found dead under mysterious circumstances, a majority of the public again began to support the "punishment". Understandably, it is so not only because they are frustrated with the existing justice system, but also because what they perceive to be "vigilante justice" is a relatively new phenomenon in Bangladesh.

But as our past experience suggests, denunciations may be used to settle scores. And that is why such methods of dispensing justice, which undercut the system, must be rejected.

Nazmul Ahasan is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. His Twitter handle is: @nazmul_ahasan_.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments