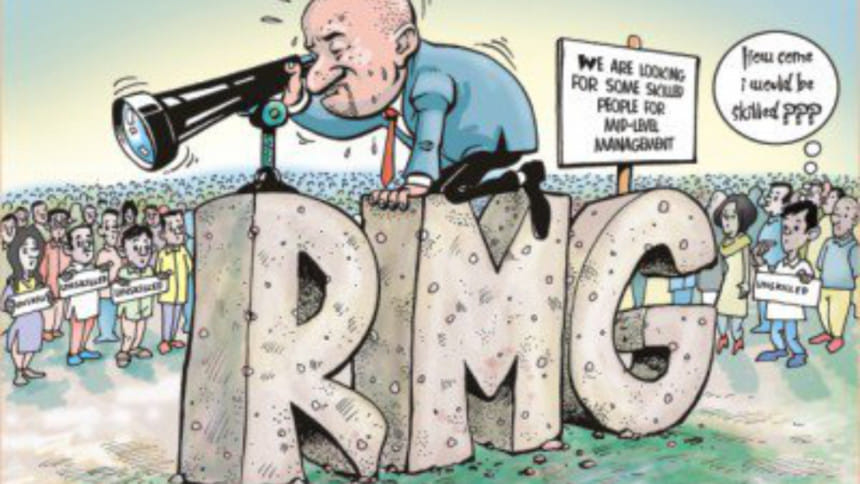

Are educational institutions failing the RMG industry?

The Bangladesh ready-made garment (RMG) industry started its journey in 1978 and 41 years later, we are still heavily dependent on imported skills at the management level. The whole education sector has failed for not taking this problem seriously. It seems foreigners are keener to study our garments sector than us.

In one of my research projects, students of Kennesaw State University in the US do Skype classes with my students to understand the Bangladesh garment industry. They have designed the course in light of our garments industry; but we don't offer any courses on our own garments industry in most of the universities. Our educational institutions are not creating enough skilled management level people for the RMG sector.

Out of 126 universities (46 public and 80 private) there are two universities in the country—BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology (BUFT) and Bangladesh University of Textiles (BUTEX)—that have been established for the garments and textiles industry specifically. Among private universities, BUFT is ranked 25th and BUTEX 9th among public universities. Although they are not the leading universities in the country, so far, they have been doing a commendable job of producing graduates who have the skills necessary for the industry. For example, Ms Shwapna Bhowmick graduated from BUFT, and is now the Country Manager of Marks & Spencer in Bangladesh. But obviously it is insufficient considering the volume and growth of the industry in the country.

In other universities, there are some degrees such as textile and industrial engineering that also fulfil the demands of the sector. Although there are close to a hundred private universities in the county, only a handful of them offer industrial engineering. Most universities do not offer courses like industrial relations, labour management, occupational health and safety. Even leading private universities do not have a centre on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

The grooming of students to become smart merchandisers who can negotiate with buyers is also missing in our curriculum. Courses should be designed in a way that connects classrooms with industries. To ensure the structural safety of factory buildings, we have an adequate number of civil engineers, but the contribution of private universities in this field is minimal. The era of complacency is over, RMG is about to face challenges from automation and competition, and the industry is not ready.

Different organisations are currently working closely with entrepreneurs to fill this knowledge gap. Here are some examples of how the capacity building programme of garments and textiles have been connected with the factory management. The IFC's (International Finance Corporation) PaCT (Partnership for Cleaner Textile) to address high water, energy, and chemical use; ILO's Better Work programme emphasising on working conditions; Palladium International's Sudokkho to produce skilled workers; BSR's (Business for Social Responsibility) health project; Alborg University's Master's degree in Risk and Safety Management. The list of examples could be longer, but the point is that there should be more courses offered in leading private universities that are directly linked with the garments industry. Doing research on this field is not enough, we need to generate a good number of quality graduates with expertise on the garments and textiles industry.

Producing high skilled workers for the RMG industry will also contribute to the economy by reducing the amount of foreign remittance that leaves the country. Around 13 percent of the country's garments factories have employed foreign experts in the top posts who remit over USD 5 billion from Bangladesh every year (CPD 2018). In the absence of a skilled workforce, particularly in merchandising, design and marketing, as well as in operation of sophisticated machines, the factory owners have hired experts from China, Taiwan, Japan, India and Pakistan to fill the gap. There is no harm in embracing the knowledge of foreign workers. But it is also a matter of frustration that we have failed to supply the domestic resources to occupy these positions.

It's not that we have a dearth of talent. For the first time, H&M, purchasing about Tk 25,500 crore worth of garments from Bangladesh every year, has appointed a Bangladeshi citizen as the Regional Head of Bangladesh, Pakistan and Ethiopia (November 9, Prothom Alo). According to him, foreign workers are mainly required in product development carried out in the R&D (Research and Development) department. That indicates that the other job positions would be occupied by the domestic workforce if they were nurtured well by different universities focusing on the demand of the garments industry.

The BGMEA and BKMEA also should extend their hands to showcase the skills they are expecting from the education industry. BRAC University organised a National Career Fair recently creating an opportunity to bridge the gap between the leading companies and the graduates. I was saddened to find the presence of garments companies in this fair to be unimpressive.

According to the Mckinsey Report 2019, Bangladesh is still seen as the most attractive destination country for buyers, but the gap it has with Vietnam is closing. It is not an exaggeration to say that the garments entrepreneurs have single-handedly placed the garments and textiles industry on the global map. How high are the expectations that our entrepreneurs have from the education industry, and how badly are we failing? We believe that if we stay afloat, business will follow—I am afraid those days are gone. It is time to address the issue at earnest. "Business-as-usual" won't take the industry much further from here on.

Shahidur Rahman teaches at BRAC University.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments