Bangabandhu’s rapier-like words reflected his unswerving resolution

In the very first general elections of Pakistan held in December 1970, the Awami League won an absolute majority in the National Assembly. But for the Pakistani military junta as well as the Pakistan People's Party head Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the desire to retain control of the central government took precedence over the need to abide by democratic norms. The central government paid no heed to the Six Point demands presented by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1966, the implementation of which would have eradicated the economic and political disparities suffered by the Bengali majority since the inception of Pakistan. The Pakistani ruling minority became anxious about the Six-Point demands after the landslide victory of the Awami League. President Yahya Khan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the senior military generals became involved in machinations to prevent a political party led by Bengali politicians from forming the government in Pakistan.

On March 1, 1971, General Yahya Khan postponed the inaugural session of the National Assembly for an indefinite period. The President's announcement provoked widespread public outrage and the people of then East Pakistan ran out of patience with the unjust attitude towards them by the Pakistani military-bureaucratic authority. A storm of protest erupted across Bangladesh. Declaring that the central government's manoeuvre would not go unchallenged, Bangabandhu initiated a Non-Cooperation Movement against the Pakistani authorities guilty of repudiating the democratic process. Strikes were observed on March 2 and 3, and a public meeting was organised in Dhaka on March 7.

A few lines from the much-cited opening paragraph of Charles Dickens' famous novel A Tale of Two Cities can aptly be drawn on to describe the disorienting situation of Dhaka in the first week of March 1971. Certainly, "it was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness." Since the postponement of the meeting of the National Assembly, a premonition of ominous events loomed large in Bangladesh. Yet, infuriated Bengalis took to the streets spontaneously, chanting the slogan Bir Bangali osthro dhoro, Bangladesh swadhin koro (Brave Bengalis take up arms, and liberate Bangladesh). The demonstrators often carried bamboos and sticks and did not hesitate to defy the curfew imposed by the military administration. On certain occasions, the army opened fire on the protestors and inflicted casualties. As a confrontation with the military administration seemed imminent, trepidation grew amongst people that innocent blood might be spilled in the days to come. Yet, thousands of Bengalis, especially students and the youth, were filled with an impatient desire to hear the declaration of independence of Bangladesh by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

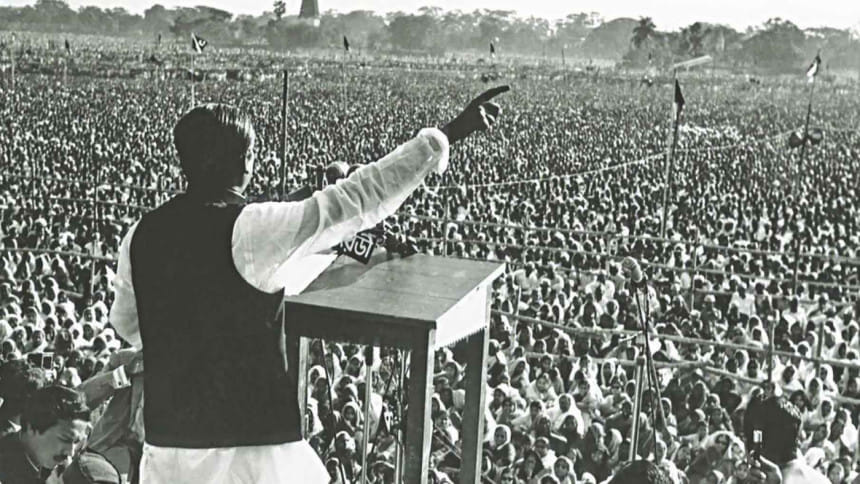

In this tumultuous situation, the public meeting scheduled to be held on March 7 at Ramna Race Course became extremely important. People from all walks of life in Bangladesh were eager to know Bangabandhu's position in that perilous situation and to receive instructions. The meeting, held in the very heart of Dhaka city, was attended by millions. Even blind young men marched in procession to the meeting. Standing before a sea of people, Bangabandhu made a speech that was characterised by a sense of justifiable anger as well as incredible poise. The 19-minute long extempore speech has gone down in history as one of the most memorable and powerful political speeches ever delivered in a grievously unstable situation. The speech also inspired people to remain resolved to fight for the much-coveted independence of Bangladesh.

Because of its enormous success in instilling courage in people in a crisis situation and in rousing them to fight oppression, Bangabandhu's March 7 speech can rightly be considered the equal of the other greatest speeches of the world—such as "We Shall Fight on the Beaches" by Winston Churchill in 1940, "I have a Dream" by Martin Luther King Jr in 1963, "Give Me Blood and I Shall Give You Freedom" by Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose in 1944, "The Hypocrisy of American Slavery" by Frederick Douglass in 1852, "I am Prepared to Die" by Nelson Mandela in 1964, and the Gettysburg Address, delivered by Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Many people anticipated and wanted that Bangabandhu would make a unilateral declaration of the independence of Bangladesh in his speech on March 7. However, Bangabandhu and the senior leaders of the Awami League realised that declaring independence would provide the government with an opportunity to unleash a vicious military assault on innocent civilians on the pretext of protecting the integrity of Pakistan. So, the speech perspicaciously avoided making the declaration, yet Bangabandhu demonstrated his fierce determination to support and strengthen the struggle of the Bengalis for freedom by declaring that Ebarer Sangram Amader Muktir Sangram, Ebarer Sangram Swadhinotar Sangram (The struggle this time is for our liberation, the struggle this time is for independence).

These valiant statements succinctly summed up the speech of Bangabandhu and also signalled his stand on the existing predicament. By describing the current rising up of the Bengalis as the struggle for freedom and independence, Bangabandhu made his directions quite explicit for the people eagerly looking forward to hearing the declaration of independence. Although independence was not formally declared in that meeting, these lines were equivalent to a declaration of independence. Bangabandhu's speech blended both agony and outrage. He lamented the cruelty and subjugation to which the Bengalis were subjected since 1952. He also informed people of the unwillingness of the Pakistani authorities at the time to ensure the creation of a democratic system. By expressing intense anger towards the way the Pakistani army had been shooting unarmed Bengalis, Bangabandhu requested the people to build fortresses in each and every house if a single more bullet was fired. He urged the people to confront the enemy with whatever they had.

By mentioning in his speech the necessity of ensuring the rights of the Bengali population, the immense strength of the unity of the 75 million people of this country and the killings of innocent civilians, Bangabandhu raised the courage and consciousness of the people of Bangladesh. He emphatically asserted that since we had given blood already, we would not fear further bloodshed but, we would liberate the people of this country by the grace of God. The unfair treatment of the Bengalis by the Pakistani authorities was scathingly denounced in this speech. However, Bangabandhu also requested the Pakistani authorities to be sensible enough to solve the problem in a peaceful manner. He requested the authorities not to try to govern Bangladesh via military rule, but later events revealed that these requests were bitterly resented by the Pakistani military junta.

Apart from the use of incandescent and courageous words, Bangabandhu's extraordinary oratorical skills lent a phenomenal quality to the March 7 speech. In that confused and agitated time, the people of Bangladesh were badly in need of the able guidance of a leader. Bangabandhu's speech not only provided the people with explicit instructions but also inspired them to face adversity with courage and determination. The Pakistani junta ignored the warning of Bangabandhu that 75 million people could not be suppressed. They launched an all-out military offensive on the Bengalis on March 25, 1971. But the Pakistani military government had not bargained for the great fortitude of the people of Bangladesh. Bangladesh won its independence from Pakistani rule after nine months through a Liberation War involving much bloodshed. The unfaltering resolution reflected in Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's historic speech of March 7 was an infinite inspiration to our freedom fighters.

Dr Naadir Junaid is Professor of Mass Communication and Journalism at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments