Bangabandhu’s writerly skills

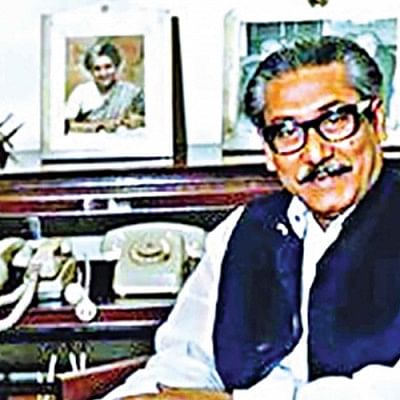

Soon after Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's Oshomapto Atmojiboni (Unfinished Memoirs)came out in an English translation as well in the original Bangla in 2012, I heard at least a few people express their skepticism about the book's authorship to me. More than one person told me (since I was the translator), "Surely, someone else wrote it for him!" After all, how could a man, known overwhelmingly as a firebrand leader and a populist to most of his contemporaries, write a 200-plus page vibrant narrative of such interest? Trying to be generous, one elderly intellectual, who knew well the political period covered in the book, and recognised the events and some people mentioned in it from living in undivided Bengal till 1947 and post-partition East Pakistan afterwards, told me, "He must have dictated the story to an amanuensis; the narrative has such an authentic feel; but, surely he didn't write it himself!" A couple of people quizzed me thus, "Did you actually see the manuscript that is the basis of the translation?" (blithely ignoring the facsimiles of some pages in his hand reproduced in the printed book), suggesting knowingly thereby that a professional writer must have embellished the events narrated, and stressing that it wasn't from his pen because it couldn't be!

The number of doubters must have decreased considerably when both Karagarer Rojnamcha and its English translation came out simultaneously in 2018. By this time, of course, a number of volumes were circulating freely throughout Bangladesh because of a few book initiatives collecting speeches that Bangabandhu had delivered or letters that he wrote.

Details of Bangabandhu's ever-active pen even in confinement multiplied when the Secret Documents of Intelligence Branch on Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman began coming out in 2019; what the Pakistani intelligence people kept noting down was how this Bengali politician's thoughts and creative endeavours kept finding outlets through the letters that he kept writing in prison. Confinement made him write on and on!And then Amar Dekha Naya Chin (New China 1952) came out in Bangla last year and this March, silencing most of the remaining doubters. Who else except the person himself could have fleshed out the experience of a China visit in 1952 recorded in 11 pages in the Unfinished Memoirs into much more detail in an extended narrative, following it up with a detailed comparative analysis of a dynamic nation seen by someone enthralled by its sights and sounds? Who, except someone deeply worried about his own people and country which was going nowhere and, indeed, already showing signs of being riven by problems created by insensitive rulers bothered only by their interests, could have penned such well-thought out and analytical comments even in prison?

But the doubters should have seen proof of authorship also in the writer's speeches. The exceptional eloquence evident in the March 7, 1971 speech and his gripping prison letters are proof (if needed!) that he could write vividly when stirred. Indeed, the three prison narratives of extended length till now are themselves the best proof that incarceration only spurred Bangabandhu to keep writing down his experiences, feelings and observations about politics and people in fascinating detail. Here was someone with a prodigious memory, exceptional communicative and rhetorical skills, interest in history, and a vast appetite for life and love of his people, making optimum use of the endless time a political prisoner has in enforced confinement, since this was the best way he could often spend sleepless nights. All alone with a pen in his hand then, and the notebooks left for him by his dear wife or the prison authorities, his moving finger kept filling page after page.

Indeed, Begum Fazilatunnesa Mujib was Bangabandhu's muse, for did she not merely exhort him to write, saying during a prison visit "Since you are idle, write about your life now", but also provide him with "some notebooks", and leave them with his jailers for that purpose?

Clearly, once he started writing, the events of his life just kept flowing in his consciousness, making him fill notebook after notebook. Since he was forced to spend his nights all alone and would often have to pass sleepless hours in intimidating surroundings and unwholesome conditions, writing was one sure way of coping with his environs and making the best use of his waking hours. And, inevitably, the sights and sounds of prison, its inmates and staff, its flora and fauna, kept finding their way into the narrative.

However, a prodigious memory, an appetite for life, slow-moving time and blank pages inviting him to fill them up are not the only reasons why Bangabandhu has left behind for posterity works of such stirring quality. He has many other writerly gifts that he could make good use of during the thousands of nights he was left alone with his thoughts and those blank pages to fill from dusk to dawn day after day. Clearly, he was someone who liked listening to stories of the inmates he came into contact with. Events happening outside like, say, the intense reaction throughout the country after February 21, 1952, also activated his conscience as well as his imagination, making him feel that he wanted to record history being made, and register a mind full of indignation at what the Pakistanis were doing, although he would have rather been outside to influence events directly for the welfare of his people.

In fact, my reading of Bangabandhu's books and coming close to them in the act of translating them made me aware of other writerly gifts that he had been endowed with. One of them is the way he could strike up relationships and get to know people. Whether it was the composite portrait he derived from the many glimpses and exchanges he had with his mentor Shaheed Suhrawardy, or his ambivalent feelings about Maulana Bhashani at a later stage of their relationship, he would pen them all down. But he could strike up conversations with all kinds of people, from convicts guilty of petty crimes to hardened criminals, whose life he would then give us glimpses of in vignettes that make for compelling reading. Clearly, empathy for human beings contributes to his writerly abilities and give his prison works great variety. His indignation with prison protocols and sufferings inflicted on inmates callously and continually, and his own personal sense of separation from not only his family, but also from his colleagues at critical junctures of the nation's evolution, make the prison narratives even more compelling reading.

But also fascinating for me is the way Bangabandhu's writings are interspersed with moments when his emotions, passions, love of beauty and historical sense enable him to make his travels come alive for readers. Readers will thus find his intense recording of the pre-partition riots in Kolkata sobering reading as well as the details he provides of life in a refugee camp in Bihar. There are also many instances of the anguish he felt in parting from short visits permitted to his family that make the narrative so very touching. In contrast, are moments of delights that he animates parts of his narratives with, as when he delights in remembering his visit to the Taj Mahal on a moonlit night, or recalls listening to the legendary singer Abbasuddin on a boat crossing the river, noting how even "the gently lapping waves were entranced by his singing." Clearly, there is a poetic side to Bangabandhu, as also evidenced by his occasional allusion to Rabindranath or Nazrul, and remembrances of key lines from their works. His admiration for the writers that he met in China, such as West Bengal's Monoj Basu, or Turkey's Nazim Hikmet, also indicates that here is a reader who not only read whatever he could access from prison libraries but also had a broad acquaintance with writers. In particular, his love of Bengali writers and love of the language surely made him the writer that he was as well as the liberator of his country for their sake!

More things could be said about what makes Bangabandhu such a compelling memoirist—a writer of compelling narratives about life in prison as well as outside it, and an outstanding witness to history being made through his pen. But I will have the space only to point out his sense of humour, his eye for details, flair for describing grand events such as the triumphant Peking parade in 1952, where he saw of a vibrant China displaying its best to assembled delegates as well as its own people. A final and contrasting point—the man who wages a war with the "crow army" in the prison yard trees disturbing everyone is the same man who writes tenderly in the Prison Diaries about the yellow birds that had not returned one year when he was serving an extended term in prison. Were they unhappy with him for some reason? Only a writer of powerful feelings and the capacity to communicate them could write such a poignant passage, as well as amusing ones about birds and of course the dominant species in such spontaneous fashion!

Fakrul Alam is UGC Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments