Bending the arc of development towards gender equality

"BRAC's approach has been to put power in the hands of the poor, especially poor women and girls," said Sir Fazle Hasan Abed.

We were sitting in his office on the 19th floor of the BRAC Headquarters in Dhaka. Abed Bhai was describing BRAC's pioneering work with women and girls. Although I had heard him recount these anecdotes many times and had also seen some of the programmes on the ground, it was always inspiring to listen to him.

Twelve million mothers learned to make oral rehydration therapy so that children would no longer die from diarrhoea. Thousands of rural women became poultry micro-entrepreneurs, rearing and vaccinating chickens and spurring the growth of a new sector in the rural economy. Hundreds of thousands of housewives trained as para-professional teachers and even larger numbers as community health workers so that elementary education and primary healthcare could be available in every village. Millions of women pulled themselves and their families out of poverty with BRAC's support, improving their lives materially and also gaining voice and respect in their households and communities.

As dusk fell over the slums and rooftops of Dhaka that evening, Abed Bhai turned from talking about what BRAC had achieved for women and girls in Bangladesh to what still remains to be done elsewhere, about where and how it must scale up, innovate, break barriers and set new records. His plans were as audacious as ever, his energy seemingly abundant. But we both knew time was running out for him and the baton must pass on to others. When we next met a few months later, it was to say goodbye as he lay in bed, his eyes closed. Weeks later, on December 20, 2019, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed passed away.

Of all the remarkable contributions for which Abed Bhai is remembered today, I believe none has been more ambitious in scale, nor more impactful in consequence, than his work to empower women and girls. His ground-breaking approaches to development turned perceived wisdom on its head and transformed the lives of millions of women and girls in Bangladesh and beyond.

"Small is beautiful but big is necessary," he said frequently—and with good reason. Scale matters if you want to end poverty, and there is so much of it, especially among women.

He often spoke of poor women as the best managers he had ever seen because with little income or assets, they fed the family, looked after the children and ran their households. "If poor women can manage poverty well, why should they not manage development?" he would say, packing in that one statement tomes of wisdom about women's agency.

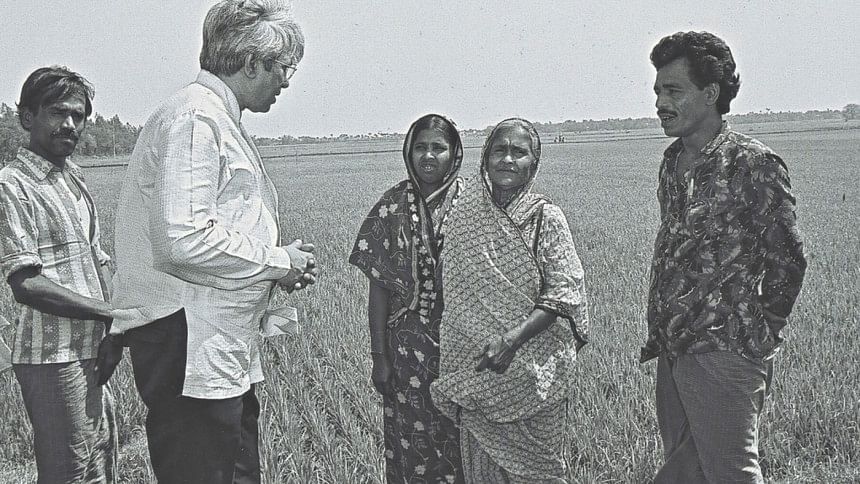

Watching women toil in the villages and small towns of Bangladesh, he saw in their thrift, ingenuity and resilience the promising talent of would-be entrepreneurs. Women became the key resource as well as the subject of BRAC's poverty eradication strategies.

With astute business sense, Abed Bhai invested heavily in women and girls through education, health, legal services and microfinance programmes, income generation opportunities, community development and social mobilisation. BRAC's approach of working directly with communities to develop solutions and of testing, monitoring and modifying programmes constantly to make them more responsive gave new meaning to women's empowerment.

Women's agency was explicit in what is one of BRAC's—and Bangladesh's—great success stories: the Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) programme. Over a decade, starting from 1979, BRAC visited around 11.8 million homes, covering 98 percent of the total rural households, to teach at least one woman in each household to make oral rehydration therapy with a three-finger pinch of salt, a handful of gur (molasses) and half a litre of boiled water. With no particular skills needed, ingredients available in every home and a simple technique for measuring, mothers produced oral rehydration solutions to treat diarrhoea and reduce infant mortality. Today, Bangladesh has one of the lowest death rates from diarrhoea and one of the highest user rates for ORT in Asia.

In the early 1980s, BRAC created income generation opportunities for women in poultry rearing and trained women to vaccinate chickens for a fee. The government provided free vaccines but there was no cold chain to carry the vaccines from the office of the sub-district livestock officer to the villages. So, BRAC devised a simple system by which the vaccines were packed inside ripe bananas to preserve the temperature and provide protection against damage during transport.

These are just a few examples of Abed Bhai's down-to-earth approach to development and his relentless drive for scaling up. He was thrifty, creative and persevering, just like the poor women he admired so much. Today, frugal innovation on scale is a badge that BRAC wears with great pride.

With his characteristic audacity, Abed Bhai carried BRAC's development models to other geographies. From adolescent girls in BRAC's schools in Helmand, Afghanistan to the BRAC community health micro-entrepreneurs in small towns in Uganda, thousands of woman and girls broke barriers to take control of their own destiny.

One of BRAC's most transformative programmes is the Ultra Poor Graduation initiative, which focuses on the poorest and most marginalised families, usually women-headed households, who are unable to afford even one full meal a day, live on the fringes of society and are caught in the inter-generational trap of extreme poverty. For two years, the women are given an income generating "asset" (such as a cow or chickens), a stipend, healthcare, and education for their children, alongside training and counselling to build their financial capabilities, a sense of self-worth and become integrated into the community. Results show that over 95 percent of the almost 1.5 million women and their families benefitting from this programme have "graduated" out of ultra-poverty, and even more remarkably, have continued to improve their lives. Many have become successful microfinance savers and borrowers.

As always, Abed Bhai was keen to scale up and readily shared BRAC's experiences with others. Today, the Ultra Poor Graduation Initiative is being replicated in 45 countries with impressive results.

Abed Bhai knew that development cannot be sustained if it does not change the social and cultural norms that hold back the progress of women and girls, but to be successful, the change itself must take into account the cultural context of the community. So, to make girls' education culturally acceptable to tradition-bound families and communities in Afghanistan, BRAC trained thousands of female teachers and engaged hundreds of older women to chaperone the girls from home to school and back. In Bangladesh, where the social context is different, popular theatre and public campaigns are used to transmit messages on gender equality, women's groups are mobilised at the village level to advocate for social change and thousands of paralegals are trained to resolve family disputes in ways that respect women's human rights.

Whether in Afghanistan, Bangladesh or many other countries, the major barrier to women's empowerment and gender equality remains patriarchal values. "Patriarchy is an enemy to both men and women," Abed Bhai declared on International Women's Day in 2018, acknowledging that gender equality was his "unfinished agenda".

Ultimately, the poor woman's struggle is not only a struggle to increase material assets but a struggle for equality, justice and dignity. Much remains to be done to make the world a safer, more equal place for women and girls. The pandemic has made that task harder, and also more urgent and vital. But when I think back to that evening in Abed Bhai's office and how he not only made the impossible possible but also sustainable and scalable, I feel optimistic. The arc of development is long but it bends towards gender equality.

Irene Khan is an international thought leader and advocate on human rights, gender and social justice issues. She is a member of BRAC International governing body.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments