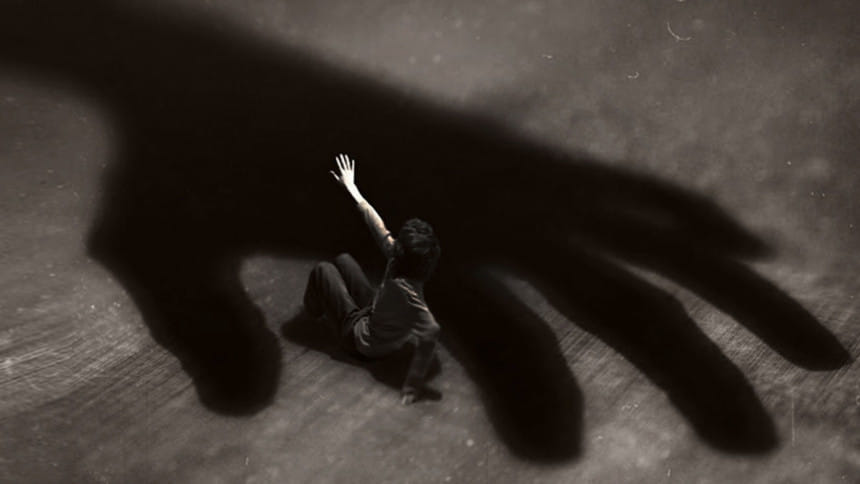

Breaking the inter-generational cycle of violence

According to the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019 by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF, 89 percent of children (1-14 years) in Bangladesh experienced violent discipline in the month before the survey was conducted. The survey also reported that 35 percent of caregivers believe that a child needs to be physically punished. There is a circular (2011) by the Ministry of Education banning corporal punishment in educational settings in Bangladesh. However, children continue to be beaten and humiliated by teachers. In addition, children are subjected to corporal punishment in homes, institutions, workplaces etc.

Corporal punishment includes any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, as well as non-physical forms of punishment that are cruel and degrading.

The high levels of corporal punishment of children in Bangladesh reflect deeply embedded social attitudes that authorise and approve it. We repeatedly hear that beatings by parents and teachers have been going on in our society for long, and this is a common practice. Some even go on to claim that they would not have been able to be who they are if they were not punished! Nobody knows how they would have turned out if parents or teachers had never hit or humiliated them. Many people deny the hurt they experienced when the adults whom they trusted the most thought they could punish them using brute force.

Some argue that many parents are bringing up their children in challenging conditions, and teachers are often under stress from overcrowding and lack of resources, and thus, they often use corporal punishment as the "last resort." In reality, corporal punishment is often an outlet for adults' frustrations in their personal and professional lives rather than an attempt to educate children. In many homes and institutions, adults need more resources and support. However, hitting children is never acceptable even when adults face difficulties.

A 2013 review conducted by the Global Initiative to End all Corporal Punishment of Children, which included more than 150 studies, showed associations between corporal punishment and a wide range of negative outcomes, and presented a convincing case that corporal punishment is harmful for children, adults and societies. This violates children's human dignity and physical integrity and is a blatant violation of children's rights. When adults hit their children in the name of discipline, children learn to "behave" only to avoid punishment, but they do not internalise why that behaviour should be avoided. So, it is very likely that they will repeat it. This means that punishment is ineffective as a disciplining technique.

There is overwhelming evidence that corporal punishment causes direct physical harm to children, and negatively impacts their psychological and physical health, education and cognitive development, in the short as well as the long run. This also increases aggression in children and is linked with violence in intimate relationships and inequitable gender attitudes. There are correlations between being physically punished as a child and attitudes favourable to corporal punishment and domestic violence in adulthood. If societies continue to allow corporal punishment of children, then it will become impossible to break the inter-generational cycle of violence.

Despite its widespread use and proven detrimental effects on children, corporal punishment remains lawful in many countries, provided that this violence is inflicted in the name of so-called discipline. Till now, only 60 countries have banned corporal punishment of children in all settings including homes. Bangladesh is not yet on the list.

When we have a legal system which states that assaulting an adult is an offence, but assaulting a child is acceptable, the law is discriminating against the child and there is no equality under the law. Laws that allow adults to inflict violence on children in the name of "discipline" represent a view of children as subordinate to adults. Reforming laws to ensure that children can no longer be lawfully subjected to violent punishment marks a turning-point in society's relationship with children, signaling the recognition of children as human beings and rights holders. In enhancing children's position in society, it advances all their other rights.

Research is showing that corporal punishment is no longer seen as acceptable and becomes less prevalent over time once it is fully prohibited. Sweden is a good example.

In 1979, Sweden became the first country in the world to prohibit all corporal punishment of children. The Ministry of Justice ran a large-scale public education campaign about the new law. Moreover, parents received support and information at children's and antenatal clinics. Since prohibition, there has been a consistent decline in adult approval and use of punishment. In the 1970s, around half of children were smacked regularly; this fell to around a third in the 1980s, and a few percent after 2000.

Ending corporal punishment is essential if we are to meet the Sustainable Development Goal's target 16.2 of ending violence against children by 2030. The following are some recommendations to end corporal punishment of children in Bangladesh.

The government circular on banning corporal punishment in educational settings must be implemented and monitored properly. A new law banning corporal punishment of children in all settings (homes, schools, workplaces, institutions including alternative care arrangements etc) should be enacted. In addition, initiatives should be taken to enforce and monitor the implementation of the legal ban through relevant policies and programmes, as well as public awareness raising campaigns.

Positive discipline in homes and schools should be promoted. This is about non-violent child-rearing and education, and giving parents, teachers and other caregivers a framework for responding constructively to conflicts with the children. The messages on positive discipline should be built into the training of all those who work with or for children and families, in health, education and social services.

Governments and other actors involved in combating corporal punishment should engage with children and respect their views in all aspects of preventing and responding to corporal punishment. Let us make corporal punishment of children socially unacceptable in addition to prohibiting this in all settings.

Laila Khondkar is an international development worker.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments