Can tertiary colleges in Bangladesh be rescued?

As reported by a national daily and some electronic media of late, the current administration is contemplating ceasing operations of around 300 private colleges for higher studies across the country. The decision comes at a time when in-person education across the country has come to a halt for many months now due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It is clear that some private colleges are in crisis, while others are not. The main accusation about these specific colleges that are facing closure is insufficient endowment to run Honours and Masters degree programmes. However, the crisis has not occurred abruptly, it has been the result of long-felt problems of tertiary colleges across the country that has never been acknowledged. This "problem blindness" has resulted in a crisis that is a warning bell for education policymakers as well as higher education administrators. Could this crisis have been avoided?

The expansion of higher education opportunities has been a key policy initiative of the current administration. In line with this policy objective, the government has been setting up public universities in districts where there are no universities, and nationalising private colleges for higher studies. On the other hand, philanthropists, political leaders and businessmen have been founding new private tertiary colleges and private universities across the country. As a result, the expansion of universities and colleges has been faster than the needs of the country. The demographic composition and economic conditions of those opting for higher studies are rarely taken into account.

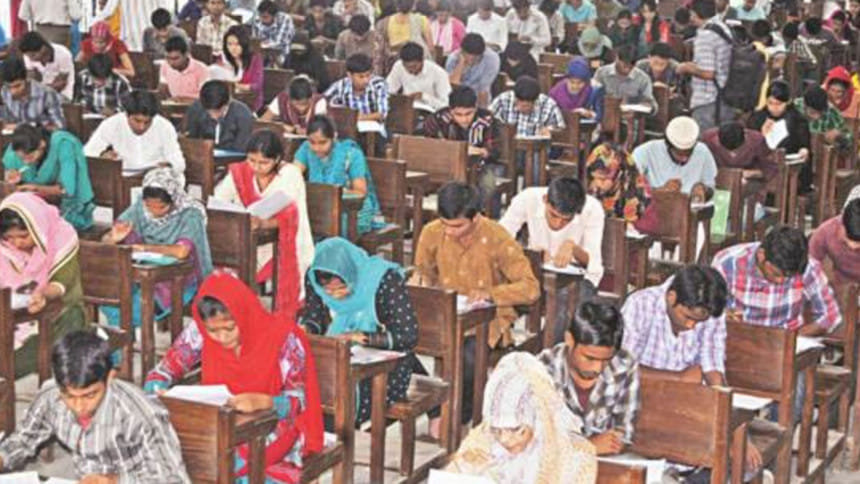

Before the Covid-19 crisis, data showed that tertiary colleges of higher education ended up with a lot of empty seats, meaning that demand for Honours and Masters degrees in colleges was not as intense as demand for higher education in universities. Academically average and less than average student performance in HSC examinations, which led to failure to secure positions in public universities, created the demand for higher education in colleges. A general observation is that studying in public universities is a matter of prestige, leading to good job prospects as well as relatively less expenditure on the education; hence, demand for higher education in public universities is high. High demand for university degrees, coupled with the limited number of seats, create very intense competition for a place in a public university. In contrast, studying in colleges is not deemed as prestigious, and the prospects of jobs for college graduates in the labour market are relatively low. As a result, enrolment in colleges can be very low. In some colleges, it is so low that they cannot generate sufficient operating revenue to pay salaries and benefits to its faculty and staff, even though before commissioning the private college, its promoter commits to the affiliating university that it shall pay its teaching and non-teaching staff fully from its own resources.

The given failure of some private colleges of higher study is, in a large part, a failure in leadership of its governing body, which is led by a president and member-secretary. An ineffective governing body structure and membership selection process is largely to blame for the resultant "problem blindness". The members of the governing body are often selected based on their political loyalty, wealth, and perceived influence in the local community where a private college is located. They are not selected for their expertise in relation to the operations of the college. Moreover, a governing body is relatively large in size, often consisting of 15 members. Because a large portion of the work is voluntary, many members are not aware of what is going on at the college and updates are provided only at governing body meetings. Unfortunately, such scheduled meetings rarely take place. In the majority of cases, the president and the member-secretary take the decisions and the outcomes are simply communicated later to the other members of the governing body. This asymmetry of information between the college administration and the governing body is extremely harmful and often intentional. Information may be withheld or kept at a superficial level so that decisions are made quickly, avoiding time-consuming due diligence and the related accountability that would come with such a process.

How can this situation be turned around? In a 2010 journal article titled "Prescription for Small College Turnaround", researcher Ruth Cowan suggests that a willing president with some leadership capacities may lead the changes, but may not make the changes happen if collaboration amongst the faculty members and other members of the governing body does not exist. Restoring financial stability is the first stage to begin with. Solvency must be restored before an institution can begin to address deeper, strategic issues. However, since the majority of higher study private colleges are very small in size in terms of student enrolment, it is not easy to achieve financial solvency.

Alternatively, small colleges that are located in close vicinity to each other may adopt the strategy of resource sharing amongst themselves, meaning that one college can share things like library facilities, laboratories and even academics with each other. This could be a simple solution to the resource constraints that they face. However, overcoming the resource problem may not result in turnaround unless the new leadership can ensure operational effectiveness in terms of efficient use of resources. Most importantly, a high level of commitment is required at the college level, so that everyone feels that their college can do something worthwhile for the community where the institution is located.

Shamsul Arifeen Khan Mamun PhD is a Consultant at the College Education Development Project (CEDP).

Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments