How could we forget our women martyrs?

When I ask students and young people if they can name some women martyrs of our Liberation War, I see blank looks or faces filled with confusion. Sometimes, a few of them would name Selina Parveen, the journalist whose name and photo appear in newspapers on the Martyred Intellectuals Day. Apart from her, hardly anyone features in their list of names. Can we blame them for this amnesia? I think we should not, because, in the last five decades, we have allowed this collective amnesia to take hold.

During the Pakistan military's genocidal campaign "Operation Searchlight" on the night of March 25, 1971, in which the military killed thousands of unarmed Bengalis, the Dhaka University community was one of the prime targets as it had been a key epicentre of the movement for democracy. The death squads unleased by the military junta killed 10 teachers and over a hundred unarmed students in their halls of residence. The killing spree was extended to employees and workers. Madhusudan Dey, owner of Madhur canteen at Dhaka University, was brutally killed along with several members of his family in the following morning. Madhusudan's wife Jogmaya Dey, son Ranjit Dey, and daughter-in-law Rina Rani Dey were also killed. Though Madhu is honoured as a "Shaheed" (martyr), Jogmaya and Rina are rarely recognised as such.

In early March 1971, the killing of Charubala in Jessore brought ordinary people to the streets to protest against the Pakistani junta. Women came out with brooms to protest at the killing and further fuelled the non-cooperation movement in the build-up to the Liberation War. Despite being one of the first martyrs of 1971, Charubala's name could not make it to any list of martyrs prepared by the state.

How many of us today know about the sacrifices of Jogmaya, Rina, Charubala, or the many other women who sacrificed their lives for the liberation of this country? How could we forget them?

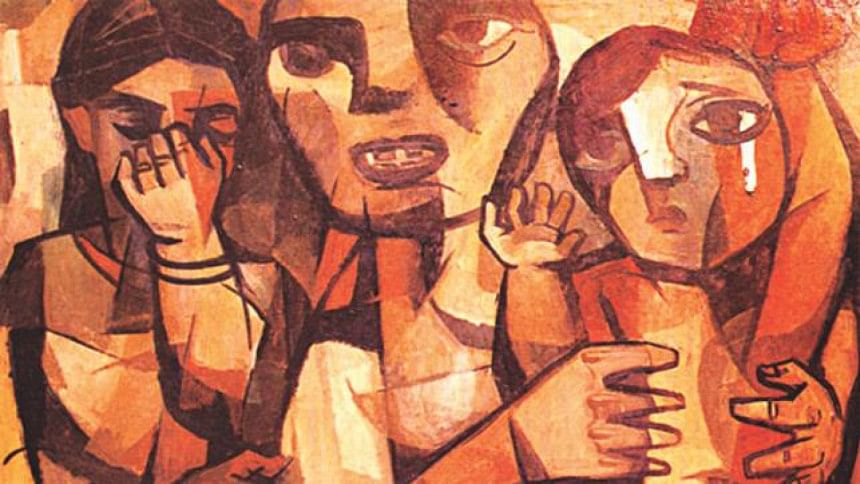

The Liberation War is presented to the post-war generation, one to which I belong, as being largely a masculine affair where women were confined only to "mainstreaming" or "stereotypical" gender roles. Beside the Biranganas, who were raped by Pakistani soldiers, any discussion of women's role usually describes women as having supported the freedom fighters with food, shelter and/or funds, or having nursed the wounded and hidden weapons risking their own lives, or having willingly sent their sons to war or lost their loved ones, or having been subjected to sexual abuse and rape. In the says-it-all discourse of the Liberation War, one common refrain is: "tirish lokkho shaheed ar dui lokkho ma-boner ijjoter binimoye ei swadhinota ("the independence was achieved at the cost of three million lives and the honour of two lakh mothers and sisters"), which tends to ignore the fact that many women sacrificed their lives for the motherland. Women are presented merely as the victims of war, rather than as actors in the liberation struggle for Bangladeshi nationhood.

Only a few names of women martyrs have made it to the pages of history books. In the national document, The History of the Liberation War: Documents, only three names of women martyrs have been recorded, but are not recognised as Shaheed. Instead, they have been described as being the "victim" of events. There are instances where the same event is described differently for men and women: the sacrifice of male members of a family is described as martyrdom while the sacrifice of women is described as "being killed". The mainstream history is constructed in such a way that "Shaheeds" are always thought to be a male figure. The state-sponsored list of martyrs contains two women martyrs: poet Meherunnessa and journalist Selina Perveen. Beside them, reminiscences of the life of Lutfunnahar Helen and Dr Ayesha Bedora Chowdhury by their family members have been documented in Smriti 1971 (edited by Rashid Haider and published by Bangla Academy). This exclusion of women's names, stories and histories remains an indispensable dimension of the masculine historiography of the Liberation War, the most glorious chapter in the history of the people of Bangladesh.

In the first two decades after the war, only a handful of books shed light on women's role but the focus was mostly limited to Biranganas. More books containing women's challenging and untold stories in 1971 started to get published in the 1990s. Stories of Taramon Bibi, Kakon Bibi, Captain Setara Begum, Sahanara Parveen and many other women came to the fore. These stories made it impossible to ignore women's brave roles, but it was also evident that there was still a lack of interest in gathering information or publishing stories about women martyrs.

I researched and compiled the stories of women martyrs Bhaghirathi (of Pirojpur), Anjuman Ara (of Parbatipur, Dinajpur), Surlala Debi (of Dinajpur), Bhramor (of Saidpur, Nilphamari), Sufia Khatun (of Saidpur, Nilphamari), Hosne Akhtar (of Saidpur, Nilphamari), Sarojini Mallick (of Saidpur, Nilphamari), Baboni Rajgour (of Patrakhola, Moulvibazar), Lasimoon Kurmi (of Patrakhola, Moulvibazar), Rangama Kurmi (of Patrakhola, Moulvibazar), Salgi Kharia (of Patrakhola, Moulvibazar), Kanakprova Debi (of Patuakhali), Sonai Rani Samaddar (of Patuakhali), Bidhyasundari Das (of Patuakhali), Sabitri Rani Dutta (of Patuakhali) and Kiron Rani Saha (of Bhanga, Faridpur). These are just a few names among the hundreds of thousands of women martyrs.

A lot of women were killed in the Pakistani army camps in 1971. There is no document or statistics about the number of women killed in the camps. Those women have never been treated as martyrs either by their family or society and the state. Many eyewitnesses told various news media platforms about their experiences of discovering women's body in mass graves and finding women's hair, glass-made bangles, sarees and women's skeletons in the camps run by the Pakistan army.

It was remarkable to find how gender-based memory and amnesia operate in historical data collection. For my research, I interviewed some people who had lost both of their parents in 1971. Many of them had vivid memories of the father but only fleeting memories of the mother. They explained that they had not been asked about the mother before, and most of the time they only talked about the father. Since they were not used to talk about the mother, they forgot many things associated with her. It is a sorry state of our societal reality that women get little importance whether alive or dead.

This must change. We need to get ourselves out of the masculine historiography of the Liberation War.

Forty-eight years is too long a time to wait for the recognition of our women martyrs. The state should waste no more time to begin a process of recognising and identifying these women. They deserve the honour, and we must ensure that they get it.

Zobaida Nasreen teaches anthropology at the University of Dhaka. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments