How ‘kowtow’ degenerated into depravity

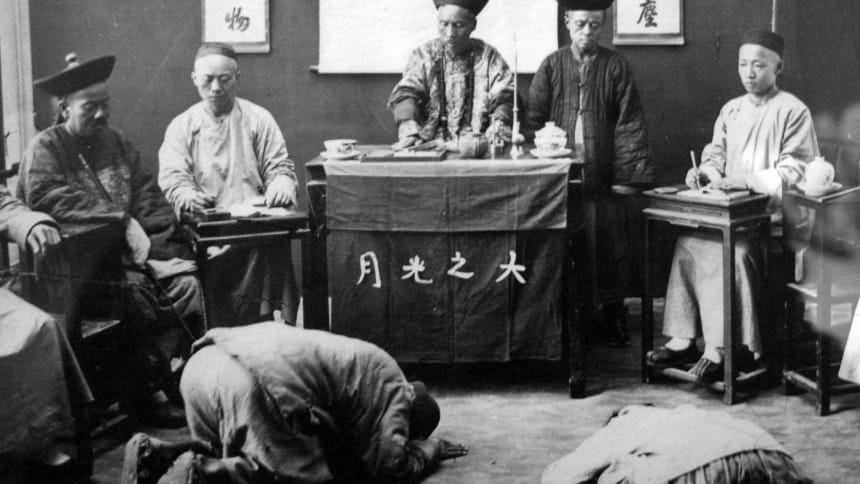

The practice of kowtow dates back to the Qin Dynasty, when subjects prostrated in front of emperors to pay their respects. It was also practiced in the courts of rajas and maharajas in India; the projas had to prostrate and put up a demeanour of submissiveness to heighten their expression of respect.

It is still in practice in Buddhism today; groups of three prostrate before Buddhist statues and images or tombs of the dead. Hindus also prostrate to pay respect to their deities in temples, and Muslims in the Indian sub-continent bend to touch the feet of the elders to pay respects.

It was only after foreigners from the West visiting China found the practice disdainful that the word "kowtow" came to mean "submissive". European emissaries in the late 18th and 19th centuries often refused to kowtow to the emperor. The former American President and diplomat John Quincy Adams, after carefully studying the records, concluded that the first Opium War (1839-1841) was not about opium at all, it was about kowtow. Lord Macartney, the first British ambassador to China, referred to the ceremonial actions of Chinese officials for kowtow as "tricks of behaviour".

Behind the concept of kowtow was the idea of seeking favour through cringing. One Vedic principle holds that "sacrifice is a gift that compels the deity to make a return—I give so that you may give me." And in Greece, Plato wrote: "Is not sacrifice a gift to God and prayer a request?"

Kowtowing was very subjective. In ancient China, it was viewed as a form of art. How well one prostrates, pays his or her respects, can be subject to interpretation; and therefore, not doing well could be subjected to denial, exclusion and sanctions. One, therefore, had to do better than others to gain favour. Aristocrats in China and elsewhere placed their sons and daughters with wealthier and well-connected families to make them learn the "tricks of behaviour", and thus help to go up in social status.

Kowtow, overtime, came to be measured more objectively; it was not just the physical act of prostrating, but also what came with it. The "art form" of kowtowing mutated from the spiritual form of respect, blessings and submissiveness to the more material forms of incentives, gifts, and favours. It has now come to be defined more by "what material wealth is offered" and what "it brings back (favours like deals, businesses)". It thus jumped from the art of paying respect to what anthropologists have long described as the important role that gifts of commodities and money played in everyday life and in religious exchanges.

While words of flattery, hyperboles, the company a person keeps, were still used with success, at others times, it was the offering of material wealth (bribery), which opened the possibility of gaining recognition and prominence. Over time, the latter gained in importance.

The second Opium War would not have been fought if there was successful kowtow. In the more recent days, the Saddam Husseins, Gaddafis and bin Ladens—despite their dictatorial images, alleged wrong doings, and repressions—could have done better if they kowtowed better to the dominant West and allowed it to access their oil wealth or resources, or submitted to their wish. Similarly, China's Huawei probably did not kowtow well and therefore it faced the wrath of the US, and its Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou got arrested in Canada.

In everyday life of today, the kowtow surrogate—money in exchange for favour—has penetrated deeply into the social fabric of most countries. It is a risky business, but those successful can make huge gains depending on their skills. Its spread is so much in today's developing countries that it can be considered even deadlier than Covid-19!

Most developing countries are afflicted by this surrogate of kowtow. Bangladesh had some serious financial debacles: the Hallmark-Sonali Bank scandal in 2012 (USD 455 million in bad loans), the stock market debacle in 2011 (40 percent decline in two months), the regular swindling of banks for huge loans, and the Bangladesh Bank heist of USD 81 million in 2016. But the most dangerous of these is probably the recent Regent and JKG debacle, in which huge amounts were made illegally, paralleling the recent Theranos scandal (a Silicon Valley start-up) masterminded by Elizabeth Holms and exposed by The Wall Street Journal's John Carreyrou. Details of who paid whom to get favour is not still clear. But there had to be some exchange of favour to protect the criminals involved.

These perverted skills of cosying, trickery, influence and swindling of modern-day kowtow are not the sole preserve of developing countries; developed countries do have many such instances as well: the more famous among them are the kowtowers like Lord Gordon, Charles Ponzi, Soapy Smith and Cassey Chadwick. Stricter oversight and better governance in developed countries make such "illegal ways" of securing influence and getting benefits difficult, but not impossible. One typical example is the recent case of Theranos (mentioned above) which raised multibillion dollars under false promises, and ruthlessly gagged employees to stop any disclosure. Many of such evildoers escape the justice but when they are caught, they have to pay a heavy price.

In developing countries, with generally poorer governance, the risk of kowtowing can be much less, and therefore kowtowing, big and small, in many spheres of life are quite prevalent. If one does have the art of kowtowing and can do it with finesse, why a person should not, especially if there is a low risk of being caught? And in the case of getting caught, there could be people of influence who would be ready to defend them and help them shrug their responsibilities.

People of book and knowledge and with high morality are therefore at a disadvantage vis-à-vis these kowtowers. One may have high skills and high morality, but they may find the entry into the inner circle of influentials difficult. On the other hand, the kowtowers, armed with the skills of swindling, may glide past all the barriers with ease. In such circumstances, the inevitable happens. The bad drives the good out.

It is extremely difficult to stop kotowing. It comes in the guise of civility, ride on false but dazzling promises, "positive" approach, innovativeness, charity, "free social service", etc. It can start benignly, from "yes sir, can do it", to gradually capturing critical public services, such as public health on which lives of ordinary citizens depend. The recent Regent/JKG incidents in Bangladesh are examples of such vicious conniving motives of making money by putting peoples' lives in danger.

It is not difficult to stop this. Simple and transparent guidelines, active oversight, zero tolerance for such crimes, strong intentions to bring the culprits to justice, and dispensing justice quickly are important for ending such social malaise. More important, however, is the protection of the whistleblowers and journalists who can expose such wrongdoing without fear or favour, as in the case of The Wall Street Journal journalist John Carreyrou, who exposed Theranos.

Dr Atiqur Rahman is an economist, ex-adjunct professor at the John Cabot University, Rome, and ex-Lead Strategist of IFAD, Rome, Italy.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments