No country for Bangladeshi women

The story of migrant labour has two polar opposite faces in Bangladesh—one is the "success story" of hard-earned foreign exchange being sent back to the country by our dedicated migrant workers, keeping their families afloat and propping up the economy as well. The other side of that story is one of vulnerability, exploitation and the dehumanising of migrant workers, turning them into products for sale in a market where the cheaper the cost of labour, the higher the margin of profit.

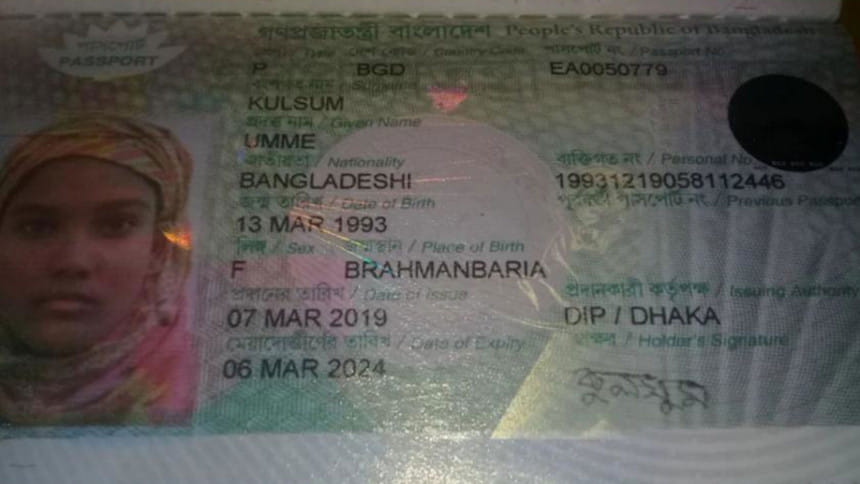

Most recently, the face of this dehumanisation has been 14-year-old Kulsum, who was sent to Saudi Arabia as a domestic worker with false documents in April 2018 by the recruiting agency M/H Trade International. On September 12, she was returned to her family in Bangladesh in a body bag. Her lifeless form was covered with signs of torture—her employers had allegedly beat her mercilessly, breaking her legs and arms and damaging her eyes.

Kulsum is not the first female Bangladeshi migrant worker to be tortured and killed in their host country. According to the Expatriate Welfare Desk at the airport, from 2016 to 2019, the bodies of 410 female migrant workers were returned to Bangladesh, with the highest number coming from Saudi Arabia (153), followed by Jordan (64) and Lebanon (52). What is the price of their lives? Data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET) suggests that out of the USD 16 billion of remittances sent home by migrant workers in the fiscal year 2019-2020, the highest portion came from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (USD 3.5 billion).

Given this amount, it is perhaps no surprise that the bulk of Bangladeshi migrant workers end up in the KSA—57 percent of documented Bangladeshi migrant workers were based there in 2019; out of over 18,000 documented female Bangladeshi migrants, over 10,000 were in Saudi Arabia alone, mostly working as domestic workers. This is despite the fact that Human Rights Watch (HRW) has described the conditions of foreign domestic workers in the country as "near-slavery", attributing them to "deeply rooted gender, religious, and racial discrimination". Last year, at least 800 female migrant workers returned from KSA after being tortured and sexually abused, according to the Brac Migration Programme. After Kulsum's death, The Daily Star interviewed other migrant workers, recently returned from the same country, who also recounted terrible stories of sexual violence, imprisonment and starvation. These women had no legal protections and no access to justice, were unable to contact their embassies, and were abandoned by their recruiting agencies.

It is not just Bangladeshis who have fallen victim to the terrible violence inflicted on domestic workers by certain employers—the KSA has been criticised for years by rights organisations for not only failing to protect foreign domestic workers from their employers, but also for creating conditions that trap workers with their abusers with no recourse to justice. In a Guardian report from 2013, an HRW spokesperson said: "The Saudi justice system is characterised by arbitrary arrests, unfair trials and harsh punishments. Migrants are at high risk of being victims of spurious charges. A domestic worker facing abuse or exploitation from her employer might run away and then be accused of theft. Victims of rape and sexual assault are at risk of being accused of adultery and fornication." Although a 2015 amendment to KSA migrant labour laws criminalised certain abusive labour practices (confiscating passports, working without contracts, etc.) and strengthened certain labour rights (paid leave, injury compensation, etc.), it excluded domestic workers, who are still at the complete mercy of their employers due to the horribly restrictive kafala (visa sponsorship) system. If anything, the institutional bias against female migrant workers has become even more entrenched in Saudi law.

In 2014, the Indonesian government paid USD 2.1 million in "blood money" to save Indonesian maid Satinah binti Jumadi Ahmad in Saudi Arabia, who was on death row for murdering her employer. According to Indonesian rights group Migrant Care, Satinah had been regularly abused by her employer, and had finally snapped and retaliated in self-defence. In 2018, the authorities of this Gulf state were strongly condemned by Indonesian officials for executing domestic worker Tuti Tursilawati without even informing her family or the consular staff. Migrant Care alleged that Tuti had murdered her employer while defending herself from being raped. While these stories of abuse are eerily similar to the ones recounted by Bangladeshi workers who have returned from the KSA, there is a marked difference—their country of origin vocally and publicly condemned the country for violating the rights of these women, even going as far as paying two million dollars to save one of them. Can female migrant workers from Bangladesh expect the same treatment from our authorities?

If we look at the case of M/H Trade International alone, there is little room for doubt regarding our authorities' stance. The allegations against this agency surfaced as early on as 2017. In 2018, one returnee domestic worker, sent to KSA by this same agency, spoke out on how she was raped, starved and finally pushed off the roof by her employers, leaving her permanently disabled. Not only did M/H Trade International not help her, she was even raped by their local recruiting agent. Yet the Rab raid of this agency's office and arrest of its agents only occurred in 2020. Why did this take so long? How did this agency manage to get a fake passport for Kulsum and send her abroad through completely legal migration channels, with the blessings of the BMET stamped on her documents? Why did the Bangladeshi embassy in Riyadh fail to protect Kulsum and so many of our own?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is no clear data on how much money the recruiting agencies and other interested parties (such as dalals or brokers)actually make from the trade in human labour. However, it is common knowledge that transnational syndicates resembling trafficking rings exist to profit from this lucrative trade at the expense of migrant workers. It is also quite clear that it is not possible for these agencies and brokers to operate, in both host and origin countries, without the support of corrupt officials who are getting a slice of the migrant trade pie.

And what do our female migrant workers—those who managed to survive their traumatic experiences but will carry these scars for the rest of their lives—get? No justice in either host or origin country, and the knowledge that their exploitation and torture is considered, by all accounts, to be the unfortunate side-effect of a multibillion-dollar and completely legal industry. The abuse of a few hundred women pale in comparison to the golden ticket of USD 3.5 billion, not to mention the unaccounted-for bulk profits being pocketed by those pulling the strings in the "manpower" trade. In fact, the only issue that Bangladesh and KSA are currently debating is the outrageous demand that Bangladesh provides passports to thousands of Rohingya refugees who are seeking protection within Saudi borders—the exploitation of our workers is almost always kept on the back burner.

Even as you read this, Bangladeshi workers are scrambling to manage airline tickets that will get them back to their workplaces in Saudi Arabia. Many of these workers were unjustly deported during the start of the pandemic, when foreign workers were scapegoated for spreading coronavirus. (The fact that high transmission in these communities reflected the often abysmal conditions they live in was swept under the rug.) Many are in debt after selling whatever little land they had to pay recruiting agencies for the visa sponsorship system and are tied to their employers, with no option but to return. Many of these workers are the sole wage-earners in their families and have no recourse to employment at home.

In all likelihood, a huge portion of these workers are also completely unaware of their rights and the potential exploitation they might face in their host countries. Cynics might ask, given that most of the developed world have no interest in the state of human rights and democracy in the Gulf states and are instead filling their coffers with oil money in exchange for weapons, what can smaller nations like Bangladesh do, especially when the future prospects of so many workers are at stake? But perhaps we should also ask ourselves: what is the price we are willing to put on the lives of our migrant workers, and is USD 3.5 billion worth the human cost of trading in their rights, autonomy and personhood?

Shuprova Tasneem is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is

@shuprovatasneem.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments