Once Upon a Time… in Bangladeshi Cinema

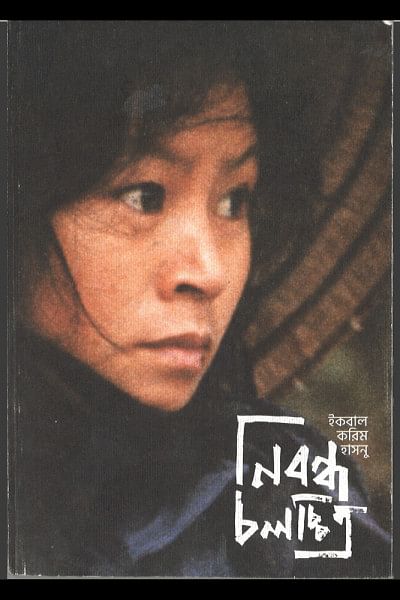

Iqbal Karim Hasnu, an author and film critic, currently based in Toronto, is also the founding editor of Bangla Journal, an annual semi-academic bilingual (Bangla and English) publication coming out of Canada. Nibandha Chalachitra (The Essay Film) is his collection of essays on world cinema, film theory, and Bangladeshi film history. The book covers the breadth of his prolific career as a critic and his lived experience as a member of the short-lived Bangladeshi alternative cinema movement.

It was the year 1983 when Iqbal Karim Hasnu first met filmmaker Tareque Masud at the study circles of Praxis Journal , led by Salimullah Khan. Like many of his peers, Masud had his beginning with Bangladesh Chalachitra Sangsad (Bangladesh Film Society) at a time when a group of "shustho" filmmakers such as Tanvir Mokammel and Manjare Hasin Murad were also active in the cinema movement.

It is difficult to translate shustho chalachitra into English without losing some of its totality. I have heard people translate it as "art film," and some members of the film movement call it "alternative film." But it translates to both and neither. Often attempting a socially conscious narrative and often paying homage to the purely artistic and textual quality of films, in a cinephile's language, shustho chalachitra should translate to Cinema with an uppercase "C." Le Cinema.

It is this Cinema that interested both Iqbal Karim Hasnu and Tareque Masud. They met in Dhaka through the alternative cinema movement of the 80s and 90s and grew closer later in Toronto, where Hasnu had moved to and where Masud would visit with his films during festivals. The two bonded over their mutual admiration for another era-defining cinema giant: Satyajit Ray.

Hasnu's love for Ray is evident in the multiple essays he wrote on the filmmaker in Nibandha Chalachitra. In the chapter "Ray-er obhijog" (Ray's accusations), Hasnu, through Ray, explores this very idea of shustho chalachitra or socially conscious films and whether they can ever attain the mass appeal of what we now recognise as masala films (think of Bollywood and Dhallywood post-90s). Hasnu investigates this concept further through the films of Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, and through the chapters on Aparna Sen and Tareque Masud.

Tareque Masud's films, especially in later years, were produced in close collaboration with cinematographer Mishuk Munier. Hasnu's introduction to Munier was through the poet Zia Haider who was staying at the author's Toronto home during a trip to Canada and had invited Munier over. Munier was working as a journalist at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) at a time when the organisation was going through rapid downsizing—the possible reason for the closure of Munier's show CounterSpin. Hasnu, too, had worked at CBC previously and was no stranger to corporate layoffs. In one of the essays in the collection, he weaves together a mini-memoir of his long conversation with Munier at St. George subway station in Toronto where the two spoke about film, documentary, and journalism.

As the author recollects in his book, he had planned a road trip with Munier from Toronto to Montreal to attend the Montreal World Film Festival the year that Tanvir Mokammel's Lalsalu and Masud's Matir Moyna had been selected. While the plan for the trip never materialised, Hasnu did attend the screening of Matir Moyna on his own. In his mini-memoir, he chronicles the feeling of joy and pride after the screening.

Matir Moyna's release in 2002 and subsequent success at Cannes Film Festival opened new horizons for Bangladeshi cinema. The story of a boy from then East Pakistan who was sent to a madrasa revealed the sensitive positioning of Islamic institutions during Bangladesh's liberation war. Despite the skilful artistry, some speculate that the 9/11 terrorist attacks worked in favour of the film's success. Hasnu writes (loosely translated into English by yours truly):

"In the post-9/11 world, when global politics had muddied the perception of Islam, Matir Moyna may appear as reactionary to Islamic radicalisation. However, the film's narrative has a lot to say about the socio-political situation of that time, making it significant for years to come."

Hasnu artfully places Matir Moyna as a response to Hussain Muhammad Ershad's military rule rather than a reaction to the 9/11 attacks. Partially based on Masud's childhood, the film attempts to deconstruct the role of religion and religious authorities during Bangladesh's independence war—an aspect the Ershad regime was working to overshadow. At a time when a group like Jamaat-e-Islami, the party that opposed the independence of Bangladesh, was being legitimised as part of a revisionist project, Matir Moyna was crucial in adding nuance to the post-independence trauma and amnesia.

In the process of canonising Masud, Hasnu comes back to Satyajit Ray whose film Pather Panchali has had an undeniable influence on Matir Moyna. The parallel is most recognisable in the character arc of Matir Moyna's Anu and Asma and Pather Panchali's Durga and Apu. Hasnu is certain that the uniqueness of Masud's films will eventually achieve a similar, if not the same, level of importance in Bengali film history as that of the films of Satyajit Ray.

The book also touches on another of Ray's filmmaking disciples: Aparna Sen. In the essay "Aparna'r Nareepath" (Aparna's feminist discourse), the author champions the trailblazing feminist philosophy in Aparna Sen's films. Referring to films such as Gaynar Baksha and Paramitar Ek Din, Hasnu observes the female lead's departure from the conventional passive heroine image in South Asian cinema.

The author takes a particular interest in Sen's treatment of sexuality in Parama and 36 Chowringhee Lane. The use of de-aestheticization in both films provides the female protagonist with an agency over their sexualisation (unlike what is imposed onto them by the cinematic male gaze). Building on the feminist theories of Jasodhara Bagchi, Hasnu remarks that this de-aestheticization works in taking back the agency that sexual women are often denied in cinema. Cinema, after all, has been instrumental in the objectification of women in contemporary visual culture, and Hasnu believes that the medium will be able to break away from that construct.

A common thread in the book is the author's regard for the New Wave. It's emblematic of the very generation that he hails from—the politically and culturally charged youth of the Cold War era. In many ways, the best essay in the collection is the introduction to his book and to the style of filmmaking that the book borrows its name from: the essay film. Hasnu builds on Georg Lukacs and Theodor Adorno, amongst others, to develop a theory on the essay film, which derives its style from the documentary style but goes beyond that when applied to fiction.

The essay film favours editing over the sound and image elements of a film in order to present an argument. The author, or filmmaker, in this case is ever so present. Naturally, the essay film was also championed by the auteur generation of Godard, Verda, Truffaut, etc., who liked revealing themselves somewhere in the narrative. The author's politics comes alive onscreen through Brechtian interventions. Blurring lines between documentary and fiction, the director is transparent about messaging.

Many film theorists, most notably Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, consider the essay film to be dialectical. Images in an essay film are essentially two-sided, and the cinematic medium not only explores the subject but also examines the ways of seeing that subject. Hasnu views this dialectical quality of essay films to be of superior value due to its ability to evoke self-reflexive inquisitions onto the audience.

Throughout the book, Iqbal Hasnu traces the emergence of essay film and its relation to global politics and Bengali cinema—and by extension, he returns to the question of how the essay film shapes his idea of shustho chalachitra. He writes (loosely translated into English by me):

"On the one hand, the country's cinema halls were filled with the tyranny of plagiarised, dumbed-down, distasteful, vulgar movies (you can hardly call them cinema at this point). On the other hand, due to the birth of video stores, middle-class households were bedazzled by grotesque Bollywood masala comedies or Dirty Harry-type Hollywood thrillers on their VCR."

According to Hasnu, while the 90s brought in a hoard of spectacle-driven cinema (what eventually evolved into "theme-park movies" à la Martin Scorsese), the essay film provoked an aggressive and urgent re-examination of the status quo. Thus, the essay film stands in support of shustho chalachitra.

Just like in an essay film, the author Iqbal Karim Hasnu is widely present throughout the book as an essential archivist of the Bangladeshi alternative film movement. The collection of essays acts as a documentation of the time and environment in which filmmakers such as Masud and Mokammel were operating, and it does so through the lens of Hasnu's personal, lived experience. Nibandha Chalachitra not only offers a lot to chew on for Bengali cinephiles interested in Fellini, Bertolucci, Kurosawa, and of course, Godard, but it also proves essential in historizing Bangladeshi cinema of the 80s and the 90s.

Nibandha Chalachitra is available at Janantik's stall # 606 at Ekushey Boi Mela and also at Charcha's stall at Dhaka Art Summit. It will soon be available on Rokomari.

Sarah Nafisa Shahid is a film critic based out of Toronto. Her writings have appeared in Hyperallergic, Wear Your Voice Magazine, and The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is: @I_Own_The_Sky

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments