Self-censorship and the media: Where are we heading?

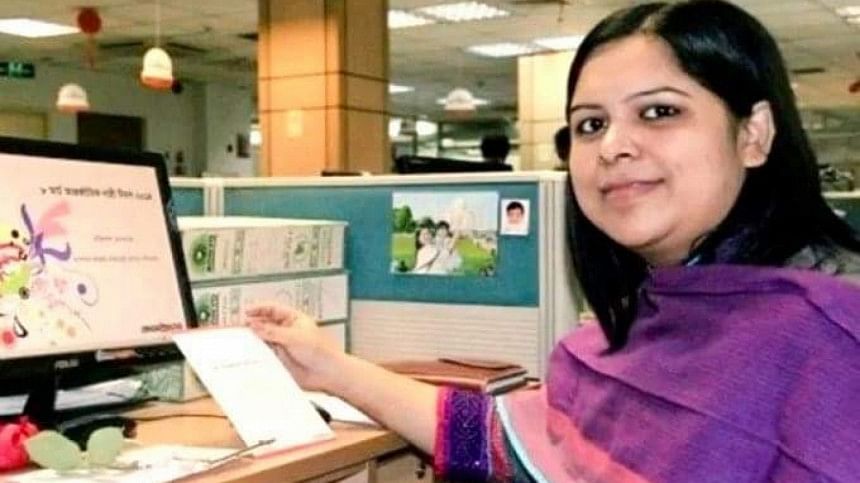

Fuelled by draconian legal measures and administrative harassment against seasoned Prothom Alo correspondent Rozina Islam, the journalistic community is fuming at the humiliating and hasty actions of the health ministry—and by definition, frustrated at the supposed inaction of the government and the judiciary to address what in reality, is nothing less than an embarrassing move to stop a journalist from doing her professional duty. Senior newspaper editors have penned columns terming the arrest of Rozina Islam as a direct attack on the media—we unitedly share their concerns. Citizens have taken to social media to remind each other of the corruption unearthed by investigative reporters like Rozina during the pandemic. With the health ministry being at the centre of these graft scandals, questions naturally arise regarding the intention behind prosecuting Rozina—we share these apprehensions unanimously as well. The question which arises as a result is this: is Bangladesh drafting its eulogy of a free media?

Rozina Islam is out on bail—yet she is in no way a free citizen. Across television talk shows, media forums and international organisations, one central concern is increasingly being expressed—the increasing usage of legal architectures that stem from the colonial era and a parallel environment of suppressing press freedom, which is widespread in Bangladesh. Whenever issues of concern are raised through the media, the state has developed a tendency to crush vocal opposition—usually citing national security concerns. The Digital Security Act for example, has been this government's primary Achilles Heel over the past couple of years—receiving criticism even from its most ardent supporters. In the first five months of 2020, 400 cases were filed and 353 arrests made under the purview of this legal instrument.

Rozina Islam's employer Prothom Alo performed an in-depth analysis of 197 such cases and reported that a high majority of these were filed based on certain vague accusations—specifically for making adverse remarks, defamation, sharing distorted images, spreading rumours and conspiring against the state. In a recent column for The Daily Star, academic CR Abrar cited the Prothom Alo report and stated that "in 80 percent of instances, the plaintiff was either leaders or activists of the ruling party or police". Abrar further pointed out that of "the 197 cases, 88 were filed by Awami League MPs, union council chairs and activists of youth, student and volunteer wings of the ruling party, and 70 more were filed by the police"—so either there is an egregious misuse of political power taking place, or if we are to believe the government, there are widespread anti-state activities being carried out against what is perhaps the strongest political regime this country has ever seen. I leave it up to the readers to decide which is true.

The current circumstances with Rozina Islam in my opinion, is symbolic of the systematic degradation of press freedom and journalism in Bangladesh—and as a result, while we condemn her detention, harassment and persecution by state authorities, we are reminded of the sobering fact that her situation is but part of a wider state mobilised censorship of the press. From the highest level of the government, to ministers, ruling party MPs to civil servants running the bureaucracy, there is a tacit message given towards non-state actors—if you cannot be with us, do not condemn us. If you cannot support us, do not criticise us. In a nutshell, the state has promoted self-censorship on part of the media by perpetuating an environment of judicial harassment and allowing for security forces as well as grassroots Awami League activists, to tap into oppressive legal tools to nullify civic opposition. This perhaps has been expressed most aptly, by the harassment carried forth by health ministry officials against Rozina Islam.

Perhaps it is a good idea to take a step back, and define what the role of free media is in developing the foundations of a thriving democracy. The press and news media is often referred to as the Fourth Estate—through indirect social influences, the Fourth Estate has the unequivocal capacity of advocacy and the inherent ability to frame political issues. Checks and balances are crucial in a political system to ensure equal distribution of power, opportunity, information and wealth—and the media acts as a guardian to ensure accountability from those wielding authority on behalf of the people. If you have an absence or deficiency in sustainable democratic exercises between political parties and in the wider public system in a society for whatever reason, the media steps in to don the role of a de facto challenger which ensures that the government of the day does not become tyrannical or dictatorial—guaranteeing that the mandate and consent of voters are considered in policymaking. Therefore in no way, should the media be an ally of either this government or of any other regimes in principle—that simply is not their role. Yes they support, yes they remind, yes they stand with you during periods of national crisis—but they are not your unwavering and unquestioning friend. And they should not be punished for not being so.

In the recent past, there has been an inclination by sycophants of the ruling party to invalidate accusations made against the government, by suggesting that the media should not put their energy in solely criticising the government—but should simultaneously market the successes of this regime. I disagree—the party in power has its army of marketing strategists who have successfully and to the fullest of their abilities, been able to promote the developmental agendas and achievements of the government. They have done so in a relatively protected digital and political space, free from political harassment and state persecution—on the other end however, with each passing day one sees a smaller space for formal dissent to take place. It is here where today's media should ideally step in—and remind the government of their failures. And failures will continue to be present—we are not a utopian wonderland and Rozina Islam's investigative pieces on Prothom Alo and the kind of journalism she represents, provides the country and its government to mend what is wrong and progress. And therefore the space and opportunity for free thinking and dissent, cannot and must not be side-lined by any political regime.

No political expert in Bangladesh will suggest that the media in its totality, is acting as a vessel on behalf of Awami League's political rivals—neither is it accurate to suggest that media personalities are fully immune from having their own skeletons. However, a cautious media which is being harassed using this country's judicial system, is practicing self-censorship in its publications—this, no editor, senior reporter or average citizen will deny. That should be our primary concern as readers and supporters of a free press. It is not a matter of national pride to see Bangladesh being ranked 152nd out of 180 countries in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index—neither is it acceptable to see a senior female journalist who has championed transparency, accountability and the concept of open government, be harassed for doing her professional job.

Rumours have circulated regarding the so-called sensitive information that Rozina Islam supposedly acquired on her phone prior to being arrested. I end this piece by asking a series of questions in this regard—if this document was so confidential, why was it left unprotected in the room of a mid-level health ministry official? On the basis of what law was Rozina kept in a confined space by health ministry officials for close to six hours and harassed by civil servants? Who gave who the right to seize Rozina's cell-phone? What message is the state giving to Bangladeshis during their Golden Jubilee celebrations by tapping into the Official Secrets Act for the first time in the country's independent history, to make a reactionary case against a journalist? And of course—should Rozina Islam be provided monetary compensation for being harassed by the very officials that she is trying to hold accountable, at a time when corruption in the health ministry is rampant? If the contexts centring around Sagor-Runi, Mushtaq Ahmed, Kajol and most recently Rozina, does not concern us as citizens, what will?

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed is a Toronto-based Banking Professional and a regular contributor for The Daily Star.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments